This story is part of a group of stories called

In July 2010, Doug Lowenstein, CEO of lobbying group the Private Equity Council, wrote a letter to PBS NewsHour after a segment it had aired on the private equity industry. He noted some “concerns” the group had with the show’s piece, including that it had ignored “hundreds of examples of PE success stories.” His chosen example: Toys R Us, which had been bought out by a trio of firms in 2005.

“[Y]ou don’t report that Toys ‘R Us was saved from likely bankruptcy by PE owners, that it has more employees working for it than it did before it was acquired, and that it is on the verge of returning to the public equity market,” he wrote.

Toys R Us never went public; it went bankrupt seven years later, in 2017. And all those employees? They lost their jobs.

The Private Equity Council, now rebranded as the American Investment Council, kept trucking along. So did the three firms that bought up Toys R Us — and, eventually, saw it go under.

The private equity industry has been under public scrutiny for years, but lately, it seems like it’s been in the headlines more. Private equity was involved in the downfalls of Payless Shoes, Deadspin, Shopko, and RadioShack. Taylor Swift has placed blame on the “unregulated world of private equity” for a battle over her music. Surprise medical bills? A private equity link. The Hollywood writers’ gripes? Same thing. Politicians are taking notice as well.

Is private equity a giant money monster that eats up companies and spits them out as the husks of what they once were, prioritizing short-term gains over creating long-term value and doing a ton of damage to everyday Americans in the process? Or does it, as some in the industry would suggest, just have a PR problem? Their argument: Sure, sometimes things go wrong, but private equity wouldn’t be in business — and have the money invested it does — if it didn’t often succeed as well. Industry advocates argue they’re taking on risk a lot of other investors would eschew, and it’s only fair they be rewarded.

Is private equity a giant money monster that eats up companies and spits them out as the husks of what they once were?

An AIC spokesperson said in a statement said that private equity firms worked “for years to strengthen and save” Toys R Us and blamed a “challenging retail and e-commerce environment” on its demise. The more cynical read: Maybe Toys R Us would have had a better chance at adapting if it hadn’t been saddled with private equity-induced debt. But of course, we’ll never know.

“Most of the time, private equity firms I do not believe are trying to drive the companies into bankruptcy, but it is what happens enough of the time to be disturbing,” said Josh Kosman, author of The Buyout of America and an expert who appeared in that PBS NewsHour segment back in 2010. “And they certainly aren’t protecting their companies from a rainy day.”

Private equity’s business model hinges on debt. A lot of it.

The term private equity can encompass a lot of different types of firms, including venture capital firms and hedge funds. But for the purposes of this story, and what you’re often hearing about in high-profile cases, we’re talking mainly about leveraged buyouts, where private equity firms buy companies basically by loading them up with debt. (Some of Vox Media’s investors may do leveraged buyouts, but Vox is not a leveraged buyout play.)

Private equity firms are, as their name suggests, private — meaning they’re owned by their founders, managers, or a limited group of investors — and not public — as in traded on the stock market. These organizations buy companies that are struggling or have growth potential and then try to repackage them, speed up their growth, and — theoretically — make them work better. Then, they sell them to another firm, take them public, or find some other way to offload them.

Generally, an ordinary investor isn’t putting their money directly into a private equity fund. Instead, private equity’s investors are institutional ones — meaning pension funds, sovereign governments, and endowments — or accredited investors who meet a certain set of criteria that allow them to make riskier bets (i.e., rich people).

You’ve probably heard of some big-name examples, such as the Carlyle Group (called out by Taylor Swift), Bain Capital (where Mitt Romney spent part of his career, and which was involved in the Toys R Us bankruptcy), KKR (which was reportedly considering taking over Walgreens and was also involved in Toys R Us), and the Blackstone Group (run by Donald Trump ally Stephen Schwarzman). If private equity firms get big enough, they sometimes start to issue stock that’s publicly traded on the broader market — shares of Blackstone, for example, have been trading on the New York Stock Exchange since 2007.

To explain leveraged buyouts in easier-to-understand terms, let’s say you buy a house. Under normal circumstances, if you can’t pay for the mortgage, you would be in trouble. But by the LBO rules, you’re only responsible for a portion. If you pay for 30 percent of the house, the other 70 percent of the asking price is debt placed on the house. The house owes that money to the bank or creditor who lent it, not you. Of course, a house can’t owe money. But under the private equity model, it does, and its assets — its factories, stores, equipment, etc. — are collateral.

The idea, in theory, behind private equity is that the endeavor will be worth it — for both you and the house. “There are many companies that, if not for private equity, would not be able to get access to the kind of capital they need to scale, to transform, to turn around, and to have succession planning,” said one industry source, who requested anonymity to speak candidly for this story.

But because of the debt companies end up owing creditors as part of a deal, they sometimes find themselves with such high interest payments that they can’t make the investments necessary to be competitive or even stay afloat. Plus, companies often take out additional loans to pay private equity investors dividends, and then they pay a fee if and when they are sold. If they can’t pay off the debt, the companies are on the hook, and their employees and customers are the ones to suffer the consequences.

And private equity’s No. 1 priority isn’t the long-term health of the companies it buys — it’s to make money, and as is the case in so many facets of investing today, to make money fast.

“Some of the larger private equity firms, they’re not retaining investments in the long-term. They are designed to produce short-term returns, and if there is nothing left of the company at the end, that’s okay,” said Rep. Katie Porter (D-CA) in an interview.

Porter represents a district the AIC touts as a success case for private equity creating jobs and making investments. She believes its methodology for calculating job creation is “highly suspect,” and it still doesn’t mean the leveraged buyout model is good: “Some of the companies they work for are owned by private equity, but that doesn’t tell us whether their family would be better off if it was on the public markets.”

“They are designed to produce short-term returns, and if there is nothing left of the company at the end, that’s okay.”

The retail industry has arguably been one of the most high-profile case studies for private equity in recent years, and you can see this setup play out again and again. People within the industry will tell you that companies such as Payless, Sears, and Toys R Us struggled because of competition from Amazon and Walmart.

But critics note that because private equity-owned companies are saddled with such a huge amount of debt, they often can’t even attempt to make the investments they need to try to keep up. Private equity’s objective, in theory, is that the company will earn enough and grow fast enough to pay down the debt to a healthy amount. But a lot of that time, that’s not what happens.

“Yes, the markets are changing. Yes, competition is difficult. But if you can retain your own resources and make the necessary investments, yes, you can compete,” said Eileen Appelbaum, a senior economist at the Center for Economic and Policy Research and an expert on private equity.

In an article for the American Prospect in 2018, Appelbaum and fellow researcher Rosemary Batt compared grocery chains Albertsons, which is held by private equity firm Cerberus Capital Management, and Kroger, which has a more conventional structure. Their findings: Kroger has been able to weather the current economic landscape better than Albertsons because it has less debt. At least Albertsons is still afloat — the pair notes that tens of thousands of jobs have been lost on account of private equity-owned grocery bankruptcies in recent years.

“If you can retain your own resources and make the necessary investments, yes, you can compete.”

The controversy surrounding private equity is that whatever happens to the company acquired, private equity makes money anyway. Firms generally have a 2-20 fee structure, which means they get a 2 percent management fee from their investors and then a 20 percent performance fee on the money they make from their deals. Basically, if an investment goes well, they get 20 percent of that. But regardless of what happens, they get 2 percent of the money they’re managing altogether, which is a lot. According to data from consultancy firm McKinsey, the global private equity industry’s asset value has grown to nearly $6 trillion.

Moreover, private equity firms can take out additional loans through their leveraged companies to pay dividends to themselves and their investors, and the companies are on the hook for those loans too. The share of profits private equity managers earn, carried interest, gets special tax treatment, and is taxed at a lower rate than regular income.

It’s heads I win, tails you lose.

Private equity isn’t always bad, but when it fails, it often fails big

Those within the industry will tell you that private equity’s goal is not to bankrupt companies or to do harm. But sometimes, that’s just what happens: Researchers at California Polytechnic State University recently found that about 20 percent of public companies that go private through leveraged buyouts go bankrupt within 10 years, compared to a control group’s 2 percent bankruptcy rate over the same time period.

Moody’s found that after the financial crisis, from 2008 to 2013, companies owned by top private equity firms defaulted on their loans at about the same rate as other companies. However, in megadeals where more than $10 billion of debt was involved, private equity-backed companies performed much worse.

Even an industry-friendly study out of the University of Chicago found that employment shrinks by 4.4 percent two years after companies are bought by private equity, and worker wages fall by 1.7 percent. The type of company matters as well — employment shrinks by 13 percent when a publicly traded company is bought by private equity, but it increases by the same percentage if the company is already private. The researchers found that labor productivity increases by 8 percent over two years.

That it is sometimes harmful to the companies it buys and, by extension, the people who work there doesn’t mean it’s not lucrative. After all, there’s a reason so many investors are parking their money in these firms. “If it were such a terrible thing, it wouldn’t have grown so big,” said Steve Kaplan, a professor and private equity expert at the University of Chicago. Blackstone, for example, made $14 billion from its investment in Hilton.

But a good deal for investors does not always translate to a good deal for other stakeholders, including employees and consumers.

Take a look at Deadspin, the sports blog that flamed out in spectacular fashion this fall just months after its parent company, Gizmodo Media Group, was acquired by private equity firm Great Hill Partners in April.

Megan Greenwell, the site’s former editor-in-chief, told me that initially the firm gave employees the impression that they were only concerned about the business side, “which had been decimated,” and didn’t plan on touching editorial.

But soon it became clear that was not the case. She said the site’s new owners didn’t appear to have much of an interest in learning about what they did or what, historically, had and hadn’t worked. “The extent to which nobody could ever articulate what their plan was … they wanted to just cut and cut and cut, which can work up to a point, but where the growth in revenue was going to come from was unclear,” she said.

Greenwell left Deadspin in August. After the site’s new managers instructed writers to “stick to sports” in an October memo, the staff resigned en masse. Deadspin stopped publishing new stories on November 4. A screenshot I viewed of Deadspin’s mid-morning traffic on December 4 showed about 400 people were currently viewing the site. Before, that number would generally be in the 10,000 to 20,000 range.

“The extent to which nobody could ever articulate what their plan was… they wanted to just cut and cut and cut.”

Representatives of Great Hill and G/O Media did not respond to requests for comment for this story.

What happened with Deadspin is emblematic of what is often a flaw in private equity, especially when it comes to big firms: They can get involved in businesses they’re not well-versed in. The Carlyle Group and other investors probably didn’t know what they were getting into when they helped producer Scooter Braun’s Ithaca Holdings buy Taylor Swift’s catalog. A decade ago, private equity firm Terra Firma learned a hard lesson when it took over music group EMI, dropped a bunch of artists to try to save money, and saw that deal turn into a disaster.

“The big private equity firms that have no idea about the particular industries in which they are investing, they think they can have this cookie-cutter model and make money. That’s where we’re seeing these terrible models happen,” Appelbaum said.

Great Hill Partners, for example, is also an investor in Bombas socks and online test proctoring company Examity.

This isn’t to say that all private equity deals and firms are bad. A lot of even the bigger firms are split into verticals by industry in the hopes of lending expertise to the companies they acquire. And there are plenty of small private equity firms out there that specialize in specific fields and make investments in relatively small companies where there is a lot of room for improvement. But those types of deals generally aren’t publicized. Small deals are “the bulk of the deals, but that’s not the bulk of the money,” Appelbaum said. Or where most workers are employed.

“Whether you’re big or small now, almost all of them are organized by industry, so when they invest, they ought to know what they’re investing in. Whether they do or not is a question,” Kaplan said.

Washington is taking notice of this, including the human cost — but it’s not clear what, if anything, will happen

Attention on the private equity industry from lawmakers has ebbed and flowed over the years, and right now, it’s under the microscope.

In July, Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) rolled out a plan and accompanying legislation — the Stop Wall Street Looting Act of 2019 — taking direct aim at the sector. Her proposal would overhaul how private equity collects fees, who’s responsible for an acquired company’s debt, and how stakeholders are paid in the event a company does go bankrupt. It would also close the carried interest loophole that keeps private equity’s taxes so low. While Warren’s bill wouldn’t end private equity, it would change incentives and force firms to have more skin in the game.

Warren and other members of Congress have called out the private equity industry over its activities in a wide range of sectors in recent months, including election technology, deforestation, and nursing homes. The House Financial Services Committee, headed by Rep. Maxine Waters (D-CA), held a hearing on private equity in November.

One private equity associate told me that at an industry conference he had recently attended, presenters framed Warren’s criticism and broader critiques of the sector as a public relations problem. He said the idea of investors being on the hook for a company’s debt was a “laugh line,” but there was an acknowledgment of the optics. “To the extent that this is what people’s view of private equity is, that’s not good for the industry or for the investors,” he said.

Emily Mendell, managing director at the Institutional Limited Partners Association (ILPA), a trade association for private equity investors, told me that it’s happened often over the years that certain headline or political events — such as the Toys R Us bankruptcy or Warren’s plan — have shined a light on the industry that is “accentuated due to the news nature of that event.” And it’s not always easy to push back. “It’s hard to tell a positive story when the negative stories — the few negative stories — will get all the press,” she said. “Private equity can’t counter what Elizabeth Warren says on the back of a bumper sticker.”

“To the extent that this is what people’s view of private equity is, that’s not good for the industry or for the investors.”

That doesn’t mean they’re not trying.

The American Investment Council (that private equity lobbying group that touted Toys R Us) has been taking out ads and writing op-eds pegged to the super-popular Popeyes chicken sandwich and pointing out the restaurant’s private equity ties. It also commissioned a report from consultancy Ernst & Young on private equity’s economic contributions that says the sector created 8.8 million jobs and its workers make on average $71,000 a year. Critics note that the $71,000 average includes people at the very top who make millions of dollars a year.

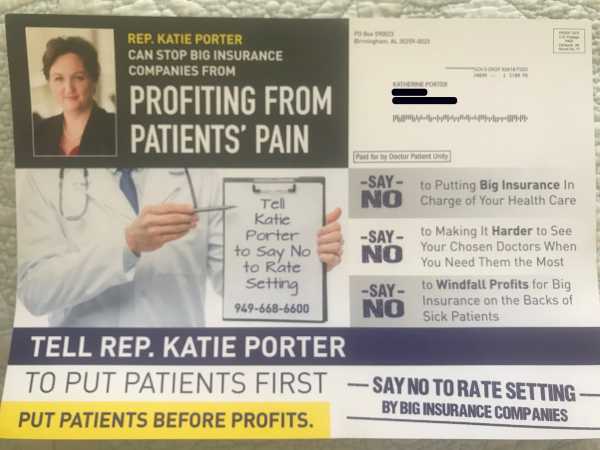

Private equity doesn’t want Congress looking too closely at their industry, but some firms are willing to quietly lobby to advantage themselves. In August, Porter, the California representative, received a mailer to her home encouraging her constituents to call her to tell her to vote against bipartisan legislation aimed at stopping surprise medical billing. It framed the bill as “rate setting” and was from a benign-sounding group called Doctor Patient Unity. It was later revealed that the group funded by two private-equity-backed companies that would lose money if the bill were passed.

Private equity sources I spoke with acknowledge that the industry has a bad reputation and that there are some bad actors — but they tend to insist that they, specifically, are doing things right, or at least trying. “In how the industry has been described, it has been painted with a very broad brush,” one of the industry sources said.

While people in the private equity industry may be complaining that it’s been unfairly caricatured, they’re not the victims. The victims are the workers who are collateral damage in deals gone bad. All those Deadspin writers who walked away from their jobs in solidarity are entering an extremely tough journalism environment right now. Just ask anyone who ever dreamed of working in local media.

More than 30,000 Toys R Us employees lost their jobs when it went bankrupt. Initially, they weren’t paid severance, even when the private equity firms walked away with millions. After months of protest, two of the investors — Bain and KKR — gave a combined $20 million to an employee severance fund, but the third investor, Vornado, abstained. According to one recent study, US retailers owned by private equity firms and hedge funds have laid off nearly 600,000 workers over the past 10 years alone.

Private equity may not be the boogeyman it’s made out to be, but it can certainly do some harm.

Sign up for The Goods newsletter. Twice a week, we’ll send you the best Goods stories exploring what we buy, why we buy it, and why it matters.

Sourse: vox.com