Finding the best ways to do good. Made possible by The Rockefeller Foundation.

The American Family Act of 2017 — a bill that would give all but the richest families at least $3,000 per year per child, no questions asked — is not famous. For over a year after Sen. Michael Bennet (D-CO) introduced it, the bill had only one co-sponsor: Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-OH), who formulated it with Bennet.

The policy, known in the many European countries where it already exists as a “child allowance,” does not have the official support of the new Democratic majority in the House, which backs a still good but more limited bill. The two frontrunners in the Democratic race for president in 2020, according to polls — former Vice President Joe Biden and Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) — have not said anything about it, to the best of my knowledge.

But I think it is quite possibly the most important legislative policy idea of the 2020 election. On the merits, the Bennet-Brown proposal is a tremendously good bill. It would cut child poverty in the United States by 45 percent, according to estimates last year from Columbia University poverty researchers Christopher Wimer and Sophie Collyer. The share of kids living in deep poverty — less than half the poverty line — would fall by more than half. And millions more parents in middle-class families would have much-needed support to pay for living expenses, afford child care, save for their kids’ futures, and more.

The bill also, I think, solves a number of important political problems for Democrats. It’s a simple, easy-to-sell proposal: “Trump said he’d help you. Instead, he gave tax cuts to the rich. We, by contrast, will mail you thousands of dollars every year, forever.” And a child allowance can be an integral part of a Green New Deal, by offsetting the increased cost of fossil fuel energy that’s an inevitable part of any real plan to fight climate change.

I think it’s realistic to hope and expect that every major 2020 Democratic candidate will support Bennet-Brown, or a child allowance of similar ambition and scale. Indeed, two likely presidential candidates, Sens. Cory Booker (D-NJ) and Kamala Harris (D-CA), have signed onto the bill just in the last month. Any other candidates looking for a trademark anti-poverty policy could do the same.

How Bennet-Brown works

The Bennet-Brown bill would substantially expand the child tax credit (CTC), which currently offers up to $2,000 a year for families with significant earnings but little or nothing for many poor people. The bill would pay:

- $3,000 per year, or $250 per month, per child ages 6 to 18

- $3,600 per year, or $300 per month, per child ages 0 to 5

Currently, only $1,400 per child of the child tax credit is refundable, and thus available to the poorest Americans who don’t owe income taxes. Even then, you have to earn nearly $12,000 to get the full refundable credit; poorer people get less, because the credit is limited to 15 percent of your earned income over $2,500. It’s a messy, complicated system that leaves out the very poorest.

Bennet-Brown wouldn’t do that. Everyone, even people with no cash earnings, would get the full $3,000 or $3,600 per year per child. The poorest would no longer be left out.

The benefits would be distributed monthly, in advance, so that families can pace out their spending and smooth their incomes. Because the CTC, like the earned income tax credit, is currently paid out through tax refunds, it sometimes leads to a perverse situation in which families use it to pay down debt they never would’ve incurred if they’d gotten the money earlier.

The credits would phase out for high-income individuals, just like the child tax credit today does, with phaseout beginning at $75,000 a year in income for single parents and $110,000 for married couples. For a married couple with two young kids, to give one example, the credits would totally phase out if the couple makes $150,000 a year or more. For families with more kids, that figure is higher.

While other Democrats have proposed major expansions to the child credit, with Rep. Rosa DeLauro (D-CT) being the most public champion of a refundable credit for young kids, this is by far the most ambitious child allowance plan any major US politician has put forward in recent memory.

The cost would be significant. A group of leading poverty experts have offered a very similar proposal and estimated its cost at $108 billion per year on top of existing child tax benefits. That plan doesn’t phase out for high earners, so Bennet-Brown likely costs less. And in any case, $108 billion per year is a totally manageable sum in the context of the federal budget. Medicare-for-all, which most 2020 Democratic contenders already support, would add some $2.5 trillion in annual expenses to the federal budget. Next to that, a child allowance is extremely cheap, and it would almost certainly do more to fight poverty.

My point isn’t to pit the ideas against each other. But if we can afford Medicare-for-all — and likely candidates from Bernie Sanders to Kamala Harris to Elizabeth Warren to Cory Booker think we can — then we can certainly afford to cut child poverty in half.

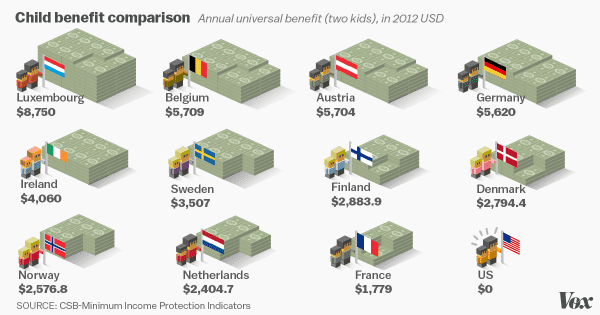

Child allowances are common abroad, and they work

A child allowance or similar policy exists in almost every EU country, as well as in Canada and Australia. In many countries, the payments are truly universal; you get the money no matter how much you earn. In others, like Canada, the payments phase out for top earners but almost everyone else benefits. France has an unusual scheme where only families with two or more children get benefits, as an incentive to have more kids.

But the core principle is the same in every system: Low- and middle-income families are entitled to substantial cash benefits to help them raise their children.

This helps explain why European countries are so much better at fighting child poverty than the US is. While about 11.8 percent of US children live in absolute poverty (as indicated by the US poverty line), only 6.2 percent of German children do, and only 3.6 percent of Swedish children do (note, though, that the absolute poverty data from LIS isn’t updated regularly and is a bit out of date).

The numbers get even worse when you define poverty like most European countries do, as living under half the median income. By that standard, 20 percent of children in the US live in poverty, compared to only about 10.3 percent in Germany or 4.9 percent in the Netherlands. This isn’t exclusively due to child benefits, but they play a crucial role.

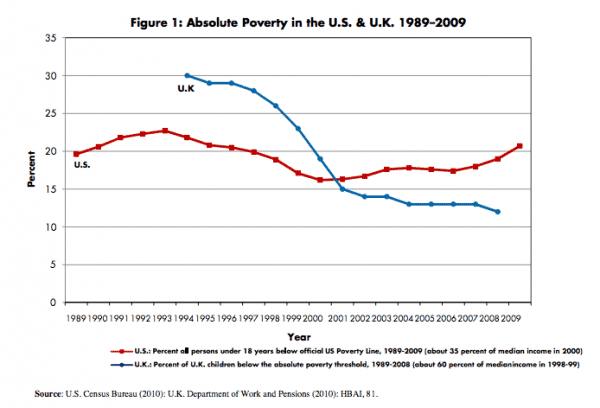

For instance, in 1999, Tony Blair and the Labour Party dramatically increased cash benefits for families with children in the UK. The measure was part of a broader set of proposals meant to tackle child poverty, including tax credits, means-tested programs, a national minimum wage, a workers’ tax credit, universal pre-K, expanded child care, and much longer parental leave.

The result was that absolute child poverty fell by more than half from 1999 to 2009, while relative poverty (the share of children under 60 percent of the median income) fell by 15 percent. The decrease in relative poverty was smaller because while things got dramatically better for the poor, the middle class gained, too.

While child poverty in the US declined slightly over the same period, a comparison of the two trend lines put together by Columbia professor of social work Jane Waldfogel is still startling:

After Blair took office in 1997, the child poverty rate in Britain began to plummet and just kept plummeting as the reforms were implemented through 2001. Then it continued to gradually decline. In the US, by contrast, child poverty fell with the late-’90s boom, and then rose in the 2000s.

The UK benefit and tax credit increases from 1997 to 2005 caused incomes for the bottom 10 percent of households to grow 20 percent, according to researchers Tom Sefton, John Hills, and Holly Sutherland.

While concerns over “welfare queens” living high on the hog and misspending benefits have often stopped the US from expanding safety net programs, there’s no evidence that child benefits would be used this way. Sam Houston State University’s Christian Raschke has found that Kindergeld, the delightfully named German child benefit program, leads families to spend more on food but not to drink more alcohol.

One study of the US’s earned income tax credit, a government benefit for working low-income families, found that receiving cash actually makes mothers more likely to get prenatal care, which in turn reduces the amount they smoke and drink. A Canadian study found that each dollar spent on child benefits reduced spending on tobacco by 6 cents and spending on alcohol by 7 cents.

What’s more, a growing body of evidence suggests that investments in early childhood development can pay off in lower crime, higher earnings, and greater educational attainment later on.

Programs that give families cash, according to UC Irvine economist Greg Duncan, result in better learning outcomes and higher earnings for their kids. One study found a $3,000 annual income increase for poor parents is associated with 19 percent higher earnings for their child once he or she grows up. That implies that a child allowance of that size could dramatically improve the lives of children decades later.

There’s plenty of other research where that came from:

- When the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians’ casino began paying dividends to its members, psychological problems among children decreased, crime rates dropped, and on-time high school graduation rates increased, according to Duke’s Jane Costello.

- Canada’s child benefit expansions boosted test scores and health outcomes, the University of British Columbia’s Kevin Milligan and University of Toronto’s Mark Stabile found.

- A short-lived universal child benefit program in Spain increased the time mothers spent with children in the first year of life, according to a study by Libertad González at Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona, and reduced the risk of couples with newborn babies breaking up.

Cash subsidies can even extend lives. Brown’s Anna Aizer, University of Toronto’s Shari Eli, Northwestern’s Joseph Ferrie, and UCLA’s Adriana Lleras-Muney looked at the Mothers’ Pension program, the first federal welfare program in American history, which ran from 1911 to 1935. They found that male children of mothers who were accepted for the program lived one year longer, got more schooling, and had incomes 14 percent greater than children of mothers who were rejected.

A child benefit would even have some effects that social conservatives might like. It encourages having more kids, and would likely reduce abortion rates by making it less costly to raise children. Money troubles are also a leading cause of marital strife, family instability, and divorce. Endicott College sociologist Josh McCabe has argued for a universal child benefit in pieces for National Review on exactly these grounds.

Why 2020 candidates should support a child allowance

The moral case for supporting a child allowance is clear: It helps children escape poverty in a really clear and easy-to-administer way. If you put the plan in the hands of the Social Security Administration and got rid of the phaseout for top earners, it would be even easier to administer. You’d help a lot of people.

But there’s also a political argument for the bill.

Earlier this year, Scott Walker, the now-outgoing governor of Wisconsin, announced that Wisconsin parents could receive $100 checks just by going online and filling out an application. The benefit was framed as a refund for “sales and use tax paid on purchases made for raising a dependent child in 2017.” His political opponents were furious. State Sen. Kathleen Vinehout, who was running for the Democratic nomination to challenge Walker at the time, said voters were being “bribed with a $100 payment.”

The implicit idea is that just giving cash to every family is so popular, so obviously beneficial and inclined to make voters like you, that it’s borderline unfair to do it. If handing out cash to parents is that politically popular and also dramatically cuts poverty rates, we should do it! One of the most difficult aspects of making policy better for poor people is aligning the interests of politicians with those of the poor. Extremely tacky, credit-grabbing cash checks to families do exactly that.

Jack Meserve, the managing editor of the center-left journal Democracy, wrote an influential piece last year calling on progressive politicians to “keep it simple and take credit.” Don’t, as Obama did as part of his stimulus package, structure tax cuts so that the government just withholds less from paychecks and people basically never know that they were getting them. Make the payments public and noticeable so voters know who sent them, like FDR did when unveiling Social Security, or George W. Bush did when he sent out $600 rebate checks as part of his 2001 tax cuts.

2020 Democrats should plan on doing that too. Maybe junk the bill’s differing payments for young versus old kids, and maybe junk the phaseout too. If you’re a 2020 contender, like Bernie Sanders or Beto O’Rourke or Amy Klobuchar, the strategy is simple: Tell voters you will give them $300 per month, per child, in a check in the mail that has your smiling face on it. Call them BernieBucks or BetoBucks or KlobKash. You will materially help people out. And you’ll have a monthly reminder sent to the homes of all your constituents, reminding them that you, unlike Trump, actually helped them out.

There’s a great bit in the pilot episode of The Carmichael Show where Jerrod Carmichael’s dad, played by David Alan Grier, confesses that he voted for George W. Bush in 2004. His liberal black family is shocked and horrified. But his explanation is simple: Bush gave him a $1,600 check in 2001. “He sent me that stimulator check. No president ever sent me $1,600. Nobody ever sent me $1,600. You can bomb whoever you want long as you send me $1,600.”

I don’t know how common a reaction that was to the 2001 tax cut checks; I haven’t read a well-designed study on the question. But I would be shocked if Bush’s checks didn’t swing some votes. And why shouldn’t they? Part of how democracy is supposed to work is by aggregating the self-interests of everyday people, so their needs and desires are represented in government. There are few better ways to show that you understand their interests than by cutting them big checks every month.

Do you ever struggle to figure out where to donate that will make the biggest impact? Or which kind of charities to support? Over five days, in five emails, we’ll walk you through research and frameworks that will help you decide how much and where to give, and other ways to do good. Sign up for Future Perfect’s new pop-up newsletter.

Sourse: vox.com