Carbon taxes are in the news these days. Longtime conservative pollster and wordsmith, Frank Luntz, recently ran a poll on behalf of the Climate Leadership Council (CLC), a group led by senior Republican statesmen James Baker and George Shultz.

The CLC is pushing a “carbon dividend” policy, which would implement a rising carbon tax and refund the revenue directly to taxpayers — while also rolling back some (allegedly) unnecessary regulations. The CLC is backed by a PAC, Americans for Carbon Dividends, run by ex-senator lobbyists Trent Lott and John Breaux. (I wrote about the CLC proposal here.)

Luntz polled the carbon dividend policy in May. It got two to one support among Republicans, four to one support overall, six to one support among Republicans under 40, and eight to one support among swing voters under 40. Once it was explained to voters in focus groups, most of them got behind it.

Related

Frank Luntz vs. Grover Norquist: the GOP’s climate change dilemma in a nutshell

Carbon taxes also came up in the first Democratic debate on Wednesday. Moderator Chuck Todd raised it with this question: “A lot of the climate plans include taxing carbon in some ways. Whether it’s Washington state where voters voted it down and you had the yellow vest movement and in Australia one party get rejected out of the fear of the cost of climate change. If pricing carbon is politically impossible, how do we pay?”

John Delaney, a former congressman from Maryland, was eager to answer: “I introduced the only carbon tax bill and economists believe it works, you have to do it right. You can’t put a price on carbon and not give the money back to the American people. My proposal, which is put a price on carbon, give dividends back to the American people.”

The existence of these proposals does indicate a heightened level of awareness of and interest in carbon taxes. So now seems like a good opportunity to review some of the basics.

Luckily, the Center on Global Energy Policy (CGEP) at Columbia University (in conjunction with several other research organizations) in 2018 issued a series of four research papers covering those basics. The research didn’t turn up anything particularly shocking; it mostly confirmed what policy wonks have long understood about the dynamics of carbon taxes.

But those dynamics aren’t necessarily well understood by the public. With the (slim but growing!) chance that a federal carbon tax could be the subject of serious national debate, it’s a good time for everyone to get up to speed.

A carbon tax is just what it sounds like — a per-ton tax on the carbon dioxide emissions embedded in fuels or other products. (Other greenhouse gases, like methane, are translated into their carbon dioxide equivalent, or CO2e, for easier comparison.)

Here are the top five questions advocates, policymakers, and informed citizens should be asking about a carbon tax:

Let’s walk through what the research shows, one answer at a time.

1) A carbon tax can lower emissions, but it needs to be pretty damn high

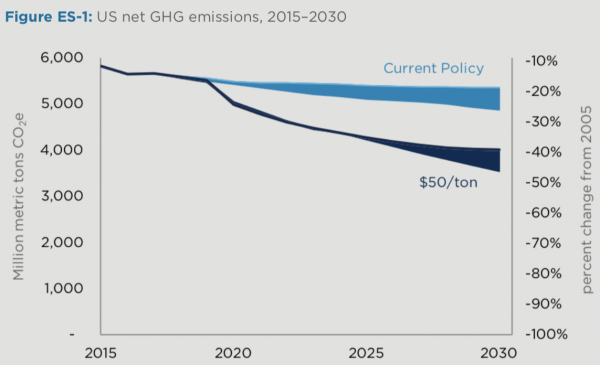

The CGEP research pivots around a few shared scenarios. Researchers modeled three different carbon taxes — starting at a per-ton rate of $14 (rising 3 percent a year), $50 (rising 2 percent a year), and $73 (rising 1.5 percent a year) respectively — with a range of fairly conservative assumptions about energy prices and technology development. The $50 tax served as the central case.

In all cases, the tax would be charged “upstream,” where carbon enters the economy, at the wellhead, mine shaft, or import terminal. The tax would ultimately cover more than 80 percent of the economy’s total greenhouse gas emissions.

The independent research firm Rhodium Group, which analyzed the energy and emission effects of a tax for CGEP, found that, sure enough, it will reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Under the $50/ton scenario, emissions fall 39 to 46 percent below 2005 levels by 2025, putting the US well ahead of its pledged Paris goal of 26 to 28 percent by 2025. (Current policy, as Rhodium’s previous research has shown, is not enough to hit that goal.)

However, none of the taxes considered are likely to achieve the long-term US emission goal of 80 percent below 2005 levels by 2050 (a target we now realize is woefully insufficient) “absent complementary GHG policies, significant improvements in technologies that can act as direct substitutes for fossil fuels, and/or significantly faster electrification of the transportation, buildings, and industrial sectors than we considered in this analysis.”

As the low-hanging fruit is consumed, emission reductions start getting more expensive. To get to 80 percent (or more appropriately, 100 percent) reductions, carbon prices would likely need to exceed $100/ton by mid-century.

2) A carbon tax hits coal first, hardest, and, at least early on, almost exclusively

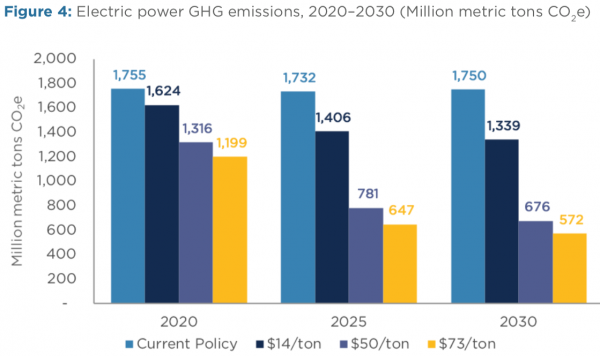

A carbon tax can reduce emissions quickly, but in the early years, reductions come overwhelmingly from a single industry: electricity.

The most striking result of the Rhodium research is that more than 80 percent of the emission reductions achieved by a carbon tax through 2030 would come from the electricity sector. More specifically, they would come from the accelerated decline of coal.

The same is not true for other sectors of the economy.

“Due to nonprice barriers, stock turnover constraints, higher capital cost to operating cost ratios, and a smaller set of abatement opportunities,” Rhodium writes, “end-use sector emissions see modest declines in emissions.”

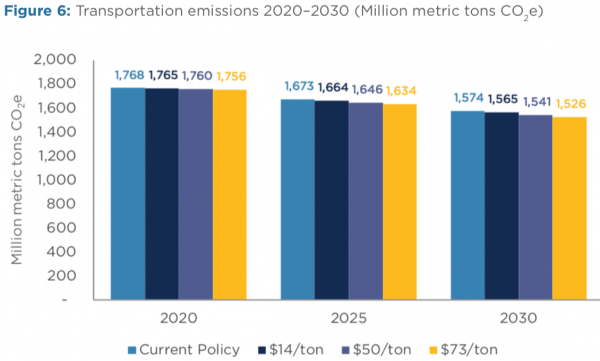

In particular, transportation appears stubbornly resistant to carbon prices. Through 2030, a $50 carbon tax would reduce emissions from the transportation sector all of … 2 percent.

Why the stark difference?

First, there aren’t easily available short-term substitutes in transportation like there are in electricity. In the electricity sector, operators can easily ramp down coal plants and ramp up natural gas plants. But in transportation, without commercially available liquid-fuel alternatives, the only way to reduce emissions quickly is to drive less, and driving behavior has proven resistant to price pressure.

Second, carbon taxes put more pressure on operating costs than on capital costs. The electricity sector is weighted toward operating costs (the power plants are mostly already built), while the transportation sector is weighted toward capital costs, i.e., the cost of buying the vehicle. A carbon tax affects the cost of running a power plant much more than it affects the cost of buying a car.

The results are not quite as stark for the industrial and building sectors, but they are pretty close. Those sectors are somewhat more amenable to price-driven carbon reductions than transportation, but not nearly as amenable as electricity (though the researchers note that uncertainty is higher in those sectors, since reporting and data are not as consistent).

3) The macroeconomic effect of a carbon tax depends on how the revenue is spent (but it’s small)

Republicans’ favorite attack on a carbon tax (or any clean air, water, or energy policy) is that it will raise costs and slow economic growth — that it will be, in the words of the anti-carbon-tax resolution the House just passed, “detrimental to the United States economy.” (By the way, 39 of the 43 Republicans in Curbelo’s House Climate Solutions Caucus voted for that resolution.)

Is it true?

The Baker Institute for Public Policy at Rice University did the research on a carbon tax’s macroeconomic effects. In a nutshell, the macroeconomic effect of a carbon tax varies depending on what the government does with the revenue.

The key point, though, is that in every scenario, the macroeconomic effect is small — well under 1 percent of GDP in either direction. The fact is, even a relatively large carbon tax won’t dramatically affect a $20 trillion economy. In practice, the macroeconomic effects of any carbon tax are likely to be lost amid larger demographic and economic trends.

The research examined three uses of the revenue through 2030:

- Using it to reduce payroll taxes would result in a net increase in GDP (of around 0.5 percent), along with boosts in “total investment, consumption, and labor supply,” because payroll taxes are distortionary and reducing them leads to more optimal economic performance;

- Using it for per-capita dividends results in a modest decrease in both GDP (0.4 percent) and consumption (0.6 percent), because “the carbon tax-induced increases in consumer prices that lead to reductions in real wages are not offset by the recycling of carbon tax revenues”;

- Using it to reduce the national debt boosts GDP 0.3 percent but reduces consumption by 0.4 percent.

As I said, all of these effects are relatively small, which suggests to me that macroeconomic effect should not be the deciding factor in how to design a carbon tax. It may be that a small marginal decline in the rate of GDP growth is a small price to pay for more justice, or emission reductions, or political durability.

One other note here: It is irksome that the only scenarios modeled are revenue-neutral. All the revenue is returned, none left for government spending.

As I’ve written before, that is an essentially conservative restriction on carbon-tax design. There’s no reason climate hawks should go along with it. The US is nowhere near overtaxed and we have lots of big spending needs if we’re going to address climate change (like, say, a Green New Deal).

So why not rebate (or reduce payroll taxes) enough to protect low- and middle-income Americans and then use the rest for clean energy infrastructure and transition assistance for vulnerable communities?

I asked Noah Kaufman, who directs the carbon tax research effort at Columbia’s School of International and Public Affairs, about this. He said it was less about researchers’ preferences than “modeling limitations.”

“Economic models in this space are typically not designed to do revenue positive scenarios,” he told me, “and in my experience, modelers are uncomfortable with the idea of projecting the economic impacts of additional government spending.” He hopes, as do I, that modelers get a little more adventurous in this respect. Of all the reasons to make a carbon tax revenue-neutral, “difficulty modeling anything else” is among the worst.

4) The equity of a carbon tax also depends on how the revenue is spent

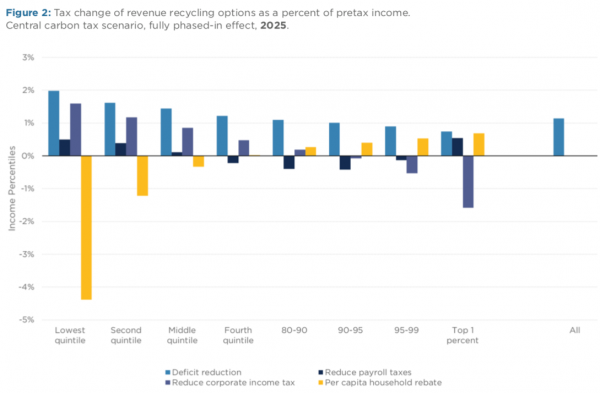

A carbon tax is, in and of itself, somewhat regressive. It hits the poor harder than the rich because the poor spend a larger percentage of their income on energy services. However, it also generates a lot of revenue — between $740 billion (in the $14/ton scenario) and $3 trillion (in the $73/ton scenario) over 10 years — which can be used to offset the regressivity.

So the distributional effects of the tax depend on how the revenue is used. We can design a progressive carbon tax if we want one.

The Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center did the research on the “Distributional Implications of a Carbon Tax.” The researchers modeled four possible uses of the revenue: “reducing the federal deficit, reducing payroll taxes, reducing the corporate income tax, and providing per capita household rebates.”

Here’s how they summarize the results:

Here’s a chart that sums it all up:

So if you’re aiming for the most net-progressive tax, you use the revenue for rebates — helps the low-income, raises taxes on the high-income. If you’re aiming to appeal to the middle class, you use the revenue for payroll tax reductions — helps the middle, increases taxes on either end.

If you’re looking to be a soulless plutocrat, you use the revenue to (even further) reduce corporate taxes, thus helping your wealthy buddies and screwing everyone else. And if you’re a daft “centrist” gripped by baseless fears about the deficit, you use the revenue to pay down the debt and pat yourself on the back even as everyone is worse off. Ahem.

It’s pretty clear that anyone concerned about the welfare of low- and middle-income Americans is obligated to support a carbon tax design that sends at least some of the revenue back to them — at least enough so that they suffer no net harm to their pre-tax income.

But, again, I’m irritated by the background assumption that all the revenue must be automatically returned, that the tax must be revenue-neutral. I’d like some modeling that reveals exactly how much of the revenue must be returned to hold low- and middle-income Americans whole. I suspect there would be quite a bit left over to spend on clean energy.

5) Carbon prices are too low everywhere they exist; they must be supplemented

Here we depart from the Columbia research and I add one answer of my own.

The economic theory behind carbon prices is that, if carbon is priced correctly — i.e., at the true “social cost of carbon” — then the economy will respond with the optimal level of carbon reduction.

There are all kinds of difficulties with this theory, not least determining the social cost of carbon, which is as much art and ethics as it is science.

But the main problem is less theoretical than practical: Political resistance has kept carbon prices well below any reasonable social cost of carbon pretty much everywhere carbon prices have been implemented. Nowhere in the US, certainly not in the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative or the Western Climate Initiative, or even the carbon tax in BC, has carbon prices close to $50/ton, which is the central case in the Columbia research. (Prices in the EU’s carbon trading system are just over $19/ton.)

And some researchers believe that the true social cost of carbon may be much higher than today’s estimates, as high as $250/ton.

Theoretically, carbon taxes can achieve any level of emission reduction. Just crank the price up — change the model inputs until you get the outputs you need. But politically, carbon prices have been constrained far below optimal levels. Nowhere, in practice, are they doing enough on their own.

Carbon taxes are a useful tool but a dangerous fetish

To me, all of the above suggests a simple conclusion: Carbon taxes are good policy, an important part of the portfolio, but unlikely ever to be sufficient on their own. It’s worth getting a price on carbon anywhere it can be gotten, but climate hawks should not believe, and definitely shouldn’t be saying in public, that a carbon price is enough, that it’s worth trading anything and everything for, that when we implement it, we are done.

For one thing, it’s unlikely to be high enough. For another, it strikes me as unwise to leave other sectors unreformed for a decade or two while we clean up electricity. If that happens, we could reach 2030 or 2040, run out of coal to retire, and find ourselves needing very rapid, very large reductions from those other sectors, for which we will be ill-prepared.

I asked Kaufman, the director of Columbia’s School of International and Public Affairs, about this as well. He noted that “it’s a feature rather than a bug of a carbon tax policy that its near-term effects are concentrated in one industry.” That should serve to reduce political opposition from oil and gas.

But he also added, “if I were developing an optimal climate policy portfolio, I’d absolutely include a host of other policies, like funding clean transportation infrastructure, efficiency standards, and a boatload of support for innovation.”

John Larsen, director of the Rhodium research, told me that the sectoral analysis of carbon tax effects can show policymakers “where to focus additional policy action.”

“A very reasonable case can be made from our results,” he said, “that more action across the economy is required if the US is going to do its fair share in tackling climate change.”

Carbon pricing, whatever form it comes in, will almost certainly need to be supplemented with technology research, development, and demonstration policies; pollution regulations; and spending on infrastructure, adaptation, and transition assistance. A carbon price supports, funds, and accelerates the effects of those other policies (which is great!), but it is not a substitute.

The proper target for advocacy is action sufficient to reduce emissions to net-zero carbon as fast as practicably possible. What limits that effort is not ultimately the choice of policy instruments, but the constraints of political attention, organization, funding, and intensity. Loosen those constraints and everything, including a carbon tax, gets easier.

Sourse: vox.com