Share

Tweet

Share

Share

Sperm counts are falling. This isn’t the reproductive apocalypse — yet.

tweet

share

It’s not just a sci-fi scenario in The Handmaid’s Tale: Actual scientists are worrying about a coming reproductive apocalypse.

You heard me right.

Over the past 30 years, as concerns that environmental changes are harming our reproductive capacity have grown, scientific journal articles have trickled out that look at whether sperm counts are declining. But those studies were often riddled with flaws and limitations, and scientists couldn’t agree on how to interpret them.

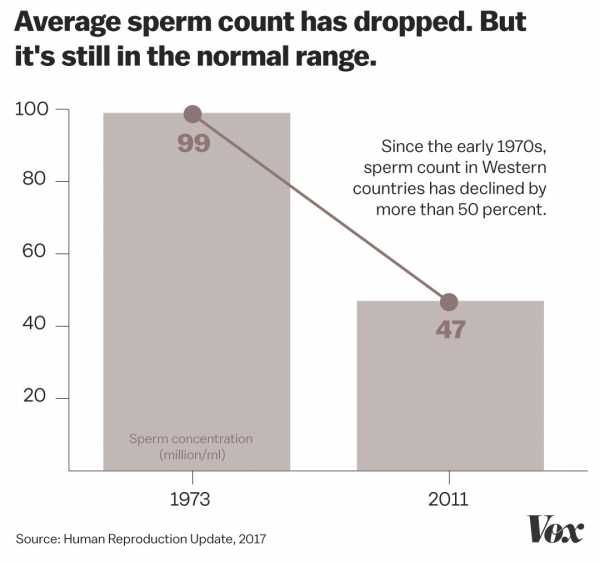

Then came what’s now considered the most definitive study on the question, published in the journal Human Reproduction Update in 2017. The finding that got a lot of attention: The concentration of sperm in semen, also known as sperm count, has halved in the West since the 1970s. The finding that got less attention: Even the new low is still well within a normal range for sperm.

In the press release for the study, the authors declared a sperm-centric public health emergency. “This study is an urgent wake-up call for researchers and health authorities around the world to investigate the causes of the sharp ongoing drop in sperm count,” said Dr. Hagai Levine, the study’s lead author, from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem’s Faculty of Medicine, “with the goal of prevention.”

Since then, online communities known as the “manosphere,” where men fret about being emasculated, have seized on the study as evidence that they are being feminized by modern society. GQ portrayed the decline as an augur of a dystopian future. “Within a generation, men may lose the ability to reproduce entirely,” Daniel Noah Halpern wrote in the magazine in September.

Lost in this conversation, as usual, is nuance about the research. I spent the past week talking to epidemiologists, andrologists (the male equivalent of gynecologists), and fertility doctors who work on male reproductive health and found a pretty stark divide. While the epidemiologists were generally more convinced by the sperm-pocalyse, the front-line practitioners treating men were not.

“If it were true [that sperm counts halved], in all the studies we do on normal young men, we’d see sperm concentrations of 30 million instead of 60 million,” Brad Anawalt, a University of Washington hormone specialist focused on male infertility, told me. “We just don’t see that.”

But even the sperm-pocalyse skeptics I spoke to agreed there’s a trend decline — it just probably looks much less ominous than The Handmaid’s Tale. So here are the sperm questions that are bound to come up — everything from what might be causing the decline to whether men are having a harder time having children — answered.

1) What are healthy sperm, anyway?

Before we get into today’s sperm troubles, let’s start with a quick primer on what healthy sperm are supposed to look like.

Sperm, as you may know, are the reproductive cells in semen, and they’re produced in the testes. “The testicle is a boiler making sperm constantly,” Paul Turek, a California-based researcher and urologist in men’s infertility, explained. And when sperm are made, they’re like a fine wine — they need to be stored and aged for 72 days before they’re ready to travel.

Once mature, they travel from the testes through a network of tubes that propel them out of the penis during ejaculation, picking up enzymes and other ingredients of semen along the way.

When doctors test sperm quality, through a semen analysis, there are a few important measures they look at:

- Sperm count (or sperm concentration): Semen that has at least 15 million sperm per milliliter is more likely to fertilize an egg, so that’s the level of concentration fertility doctors want to see in men hoping to have kids.

- Motility: To get to the egg, sperm have to be able to swim, so movement is another key measure. Men with sperm where at least 40 percent are moving are more likely to be fertile.

- Morphology: The shape of the sperm matters too. They should look just like tadpoles — immortalized in the Woody Allen classic Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex But Were Too Afraid to Ask — with little oval heads and long tails. A man’s chance of conceiving is thought to go up the more normal-shaped sperm he has.

But these measures aren’t perfect. Turek said studies on semen quality in the same man can look 100 percent different sample to sample. Some of this is because of human bias. For example, morphology is a more controversial predictor of fertility, in part because the people reading samples can have varying views on the proportion of abnormally shaped sperm. Lifestyle factors (drinking, smoking, saunas) can also dramatically change sperm quality, so a man’s semen can look very different depending on what he’s been up to recently. (More on this later.)

The sperm quality measures also aren’t always predictive of fertility. While a man with no sperm can’t father a child through intercourse, researchers have found some men with relatively low sperm counts can conceive — and others with more abundant sperm can’t.

“I always say normal is 15 million sperm per mL,” Anawalt said. “That means millions of sperm in the ejaculate. But why is it that some men can conceive and other guys with the same numbers don’t conceive? It’s a great mystery what divides those two groups of men.”

2) What has changed about sperm count in the West?

Okay, so back to the panic over falling sperm counts.

In the Human Reproduction Update paper — a systematic review and meta-analysis — researchers at Hebrew University and Mount Sinai medical school brought together data from 185 studies on sperm samples collected between 1973 and 2011.

These studies involved 43,000 men from around the world — including North America, Europe, Oceania, South America, Asia, and Africa. And they focused on sperm count (because unlike sperm morphology and motility, the sperm count metric hasn’t changed over the years). Specifically, they included only studies that collected the semen via masturbation, and used a “hemocytometer,” a counting-chamber device, to measure sperm counts.

Their major finding: Sperm counts fell by 53 percent in the past four decades in North America, Europe, Australia, and New Zealand. In the early 1970s, men had, on average, 99 million sperm per milliliter of semen. By 2011, that number had dropped to 47 million per milliliter. So with every passing year, men’s sperm count dropped by about 1 percent “with no evidence of a ‘leveling off’ in recent years,” the study authors warned.

“This was the most recent [study] trying to answer the question,” said Harvard’s Jorge Chavarro, a fertility-focused epidemiologist, who was not involved in the study, “and by far the most convincing evidence that sperm counts are dropping.”

3) Are sperm counts really falling that much?

But before we get carried away, a couple of caveats about that meta-analysis.

While the 50 percent drop in the West sounds dramatic, men’s sperm counts are still well within a normal range. As one andrology professor told the Science Media Centre, average sperm counts went from “‘normal’ (99 million sperm per mL) to ‘normal’ (47 million sperm per mL).” And again, doctors don’t start worrying until semen dips below 15 million sperm per mL.

The study authors also found the slope of the sperm count decline wasn’t as significant in the non-Western countries (in South America, Asia, and Africa), where sperm count even went up among men who were known to have fathered a child. (They thought this may be because men in non-Western countries haven’t been exposed to the same chemicals from industrial development as Western men have; more on that later.) But this raises the question of whether there’s something else that’s different about the groups or studies that might explain this variation.

Finally, the study was based on older studies done in different countries and labs. Unlike a new experiment specifically designed to test the question of what’s going on with men’s swimmers, it’s possible these older studies have important confounding factors, or unmeasured variables, that influenced the results.

Male fertility doctors, like Anawalt and Turek, also said they just haven’t seen this dramatic decline in sperm counts during their years in practice, and they’re not convinced there’s an apocalypse coming.

To truly prove sperm counts have halved, you’d need a long-term prospective study — one that looks forward in time, following men over generations, Turek said. But we don’t have that, and the 2017 study is the best data we have. Still, even critics like Turek, who disagree with the dramatic slope of the decline in that paper, believe it signals a trend. “It’s pretty convincing things are trending down,” he said.

4) What’s causing the decline?

Scientists’ best guess is that there are a number of changes in how we live that haven’t been good for sperm. Being overweight or obese is associated with poorer semen quality — and we’ve seen rates of overweight and obesity soar over the past several decades. Smoking, stress, sedentary lifestyles, and alcohol and drug use are all also implicated.

But a major factor (and one that’s surprisingly uncontroversial among scientists) is thought to be the rise of the 20th-century chemical industry.

“The leading hypothesis is that there has been a vast increase in the number and volume of chemicals that have entered the environment during the last 50 years,” Chavarro said.

Think about it. Much of the food we eat and the everyday objects we use these days are stored in or made using plastics, which contain man-made chemicals. These chemicals are also present in our creams and cosmetics, our household cleaning products, and our drugs and medical devices. They leach into our food and water, into the environment, and into our bodies.

Most are thought to be harmless. But as I’ve explained with my colleague Radhika Viswanathan, some can mess with our hormones — as “endocrine disruptors” — in ways that hamper our reproductive capacity.

Specifically, chemicals like BPA, BPS, and phthalates are known to mimic hormones like estrogen, interfere with important hormone pathways in the thyroid gland, and inhibit the effects of testosterone. And even though many companies are now manufacturing phthalate- or BPA-free products, scientists are concerned about substitute chemicals, since they’re often functionally similar to the chemicals of concern.

What this means for men’s sperm counts: Men who are exposed to hormone disruptors in utero have been shown to produce less testosterone and less sperm, and have other physiological changes associated with, as GQ’s Halpern put it, being “less male.”

For example, there’s compelling data that in utero phthalate exposure is linked to a decrease in something called “anogenital distance,” or AGD, in male babies. AGD is the space between the anus and the genitals, and a man’s is usually twice as long as a woman’s. In men, a shorter AGD has been associated with poorer semen quality, less testosterone, and a higher risk of infertility.

One of the scientists to first describe this phenomenon, Mount Sinai’s Shanna Swan, told Vox that these early chemical exposures have lifelong results. “The lowered androgen and alteration of development that happens in utero [results in] changes that are lifelong,” she said. “They are not correctable. Maybe in the future with genetic modification, you can alter a man’s germ cells that produce his sperm — but for now, if those are impacted adversely, a man will have a lowered sperm count his whole life.”

Just because there’s compelling data doesn’t mean we have airtight answers. Since we’re exposed to these chemicals from many sources simultaneously, and we were exposed to them alongside all those other lifestyle changes I mentioned earlier, it’s tricky to tease out cause and effect. For now, though, it’s the best explanation experts have.

5) But wait: are men really having a harder time having children now compared to previous generations?

The short answer: It’s hard to know.

A couple is diagnosed with infertility after one year of unprotected sex. In the US, between 12 and 15 percent of couples are unable to conceive at that point. About a third of the time, the problem is with the man. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the number of couples who would be classified as infertile, and the number of women seeking out fertility services, hasn’t changed much since 2002. (And by some measures, it’s been getting better.)

But even if the numbers were getting worse, we have to keep in mind that couples are waiting longer to get pregnant, and older age is associated with a higher risk of infertility. For that reason, even the measure of couples seeking fertility services — which hasn’t budged significantly over the past two decades — isn’t very telling.

So these aren’t perfect measures of male infertility, and the truth is we don’t have good data on whether we’ve hit a reproductive apocalypse.

In 2015, the National Institutes of Health brought together researchers from around the world to discuss the question. Importantly, they differentiated between fertility (how many kids people have) and fecundity (how many they are capable of having). Fertility rates have fallen dramatically over the past half-century, but they are heavily influenced by social factors: changes in working patterns, access to birth control, wars, the economy, etc.

Fecundity, on the other hand, is not. And the researchers determined that the question of whether fecundity is changing is currently unanswerable based on current data.

Again, even the 2017 study suggests men still have well-above-normal sperm counts on average. So the big question is what happens if average sperm counts continue their trend of decline, to the point where they fall below the levels associated with fertility. That’s what worries people — and not just because there might be fewer kids running around.

6) What if you don’t want kids? Does your sperm quality still matter?

Sperm is increasingly viewed as a little window into men’s health. So even beyond the ability to father a child, there are strong associations between poor semen quality and poor health.

In a very interesting article published in 2009, researchers followed 40,000 men who had sought treatment for infertility, tracking them for up to 40 years, and they found a striking correlation between good semen quality and a lower risk of death. “Mortality decreased as the percentages of normal and motile sperm increased,” they wrote. “Mortality also decreased as the sperm concentration increased up to a threshold of 40 million/mL, which mirrors the finding for the ability to conceive.”

Other papers on different cohorts of men have uncovered similar correlations between mortality, diseases like cancer, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease, and poor sperm quality.

“It’s clear from a number of epidemiological studies that a male’s fertility can be a determinant of his overall health,” said Stuart Moss, the director of male reproductive health at NIH’s fertility and infertility branch. “So a low sperm count is troubling from a number of areas. One is, if the trend continues, I’d imagine at some point in time we could start seeing [fecundity] decrease. But more immediately, it could be a biomarker for poor health in general.”

7) So what can men do about it?

I’m glad you asked. Because men can indeed take steps that are sperm-friendly.

Remember: Sperm take 72 days to mature in the body. After that, the mature sperm wait around to get ejaculated. In men who don’t have sex or ejaculate for a long time, those mature sperm can get funky. So one way to increase your fertility is to … have more sex. But not too much.

“The average healthy 18-year-old can ejaculate every day and recharge in time,” said University of Washington’s Anawalt. But for men in their 30s and beyond, sex two or three times per week is thought to be ideal.

Women will be glad to learn that sex with lots of foreplay is better than a quickie or masturbation when it comes to releasing high-quality sperm. “The longer you wait (to ejaculate), the more sperm come out,” Turek explained.

Besides having regular sex, there are other important things men can do to improve their semen quality (and chances of fathering a child):

- Maintain a healthy weight: Being significantly overweight and obese can mess with hormones, like testosterone, that are important for reproductive health.

- Don’t smoke, do drugs, or drink too much: Smoking is heavily associated with infertility. There’s more limited — but still concerning — evidence that using marijuana and drinking heavily hampers men’s fertility, too.

- Stay away from hot tubs and saunas: Exposing the testicles to hot temperatures is widely accepted to decrease sperm production. The fertility experts I spoke to suggested heated seats in cars, sitting for long periods of time, and holding laptops on the groin can have similar effects.

- Consider boxers: There’s some evidence that men who wear boxers have higher sperm concentrations than brief-wearers.

- Exercise and eat a healthy diet: Exercise improves blood testosterone and sperm production. A Mediterranean-style diet — favoring fresh fruits and vegetables, seafood, poultry, and whole grain — is associated with better semen quality in men.

Remember, it takes a little over two months to replenish a men’s entire sperm population in the testes. So the benefits of any of these changes may take a little while to show up in a semen analysis.

“Treat your body like a temple,” Turek tells his patients. “Pretend you’re training for a race. You need to take great care of yourself. Eat well. Sleep well. Reduce your stress. Exercise. Eat a heart-healthy diet. Your sperm count can be a biomarker of your health.”

Further reading

- Sperm Count Zero

- The US fertility rate just hit a historic low

- The 3 most promising new methods of male birth control, explained

- Is plastic microwave-safe? The short answer: often no

- The Dawning of Sperm Awareness

Sourse: vox.com