There have also been several high-profile police killings since 2014 involving black suspects. In Baltimore, Freddie Gray died while in police custody, leading to protests and riots. In North Charleston, South Carolina, Michael Slager shot Walter Scott, who was fleeing and unarmed at the time. In Ferguson, Missouri, Darren Wilson killed unarmed 18-year-old Michael Brown. In New York City, NYPD officer Daniel Pantaleo killed Eric Garner by putting the unarmed 43-year-old black man in a chokehold.

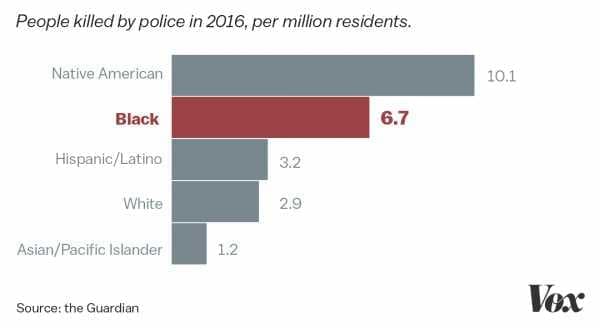

One possible explanation for the racial disparities: Police tend to patrol high-crime neighborhoods, which are disproportionately black. That means they’re going to be more likely to initiate a policing action, from traffic stops to more serious arrests, against a black person who lives in these areas. And all of these policing actions carry a chance, however small, to escalate into a violent confrontation.

That’s not to say that higher crime rates in black communities explain the entire racial disparity in police shootings. A 2015 study by researcher Cody Ross found “There is no relationship between county-level racial bias in police shootings and crime rates (even race-specific crime rates), meaning that the racial bias observed in police shootings in this data set is not explainable as a response to local-level crime rates.” That suggests something else — such as, potentially, racial bias — is going on.

One reason to believe racial bias is a factor: Studies show officers are quicker to shoot black suspects in video game simulations. Josh Correll, a University of Colorado Boulder psychology professor who conducted the research, said it’s possible the bias could lead to even more skewed outcomes in the field. “In the very situation in which [officers] most need their training,” he previously told me, “we have some reason to believe that their training will be most likely to fail them.”

Police need to own up to these problems to do their jobs

It’s these type of statistics, along with cases like Brown’s, that explain the distrust between police and minority communities. But more than simple distrust, these issues also make it more difficult for police to do their jobs and stop crime.

There’s a longstanding criminological concept at play: “legal cynicism.” The idea is that the government will have a much harder time enforcing the law when large segments of the population don’t trust the government, the police, or the laws.

This is a major explanation for why predominantly minority communities tend to have more crime than other communities: After centuries of neglect and abuse, black and brown Americans are simply much less likely to turn to police for help — and that may lead a small but significant segment of these communities to resort to its own means, including violence, to solve interpersonal conflicts.

There’s research to back this up. A 2016 study, from sociologists Matthew Desmond of Harvard, Andrew Papachristos of Yale, and David Kirk of Oxford, looked at 911 calls in Milwaukee after incidents of police brutality hit the news.

They found that after the 2004 police beating of Frank Jude, 17 percent fewer 911 calls were made in the following year compared with the number of calls that would have been made had the Jude beating never happened. More than half of the effect came from fewer calls in black neighborhoods. And the effect persisted for more than a year, even after the officers involved in the beating were punished. Researchers found similar impacts on local 911 calls after other high-profile incidents of police violence.

But crime still happened in these neighborhoods. As 911 calls dropped, researchers also found a rise in homicides. They noted that “the spring and summer that followed Jude’s story were the deadliest in the seven years observed in our study.”

That suggests that people were simply dealing with crime themselves. And although the researchers couldn’t definitively prove it, that might mean civilians took to their own, sometimes violent, means to protect themselves when they couldn’t trust police to stop crime and violence.

“An important implication of this finding is that publicized cases of police violence not only threaten the legitimacy and reputation of law enforcement,” the researchers wrote, but “they also — by driving down 911 calls — thwart the suppression of law breaking, obstruct the application of justice, and ultimately make cities as a whole, and the black community in particular, less safe.”

That’s why, especially in the context of racial disparities in police use of force, experts say it’s important that police own up to their mistakes and take transparent steps to fix them.

“This is what folks who rail against the focus on police violence — and pull up against that, community violence — get wrong,” David Kennedy, a criminologist at John Jay College, previously told me. “What those folks simply don’t understand is that when communities don’t trust the police and are afraid of the police, then they will not and cannot work with police and within the law around issues in their own community. And then those issues within the community become issues the community needs to deal with on their own — and that leads to violence.”

Cases like Brown’s feed into the distrust — by signaling to black communities that police aren’t there to protect them but are instead likely to harass them and use excessive force. In that way, these cases make it a lot harder for police to achieve the basic roles they’re meant to fulfill.

For more on American policing’s problems and how to fix them, read Vox’s explainer.

Sourse: vox.com