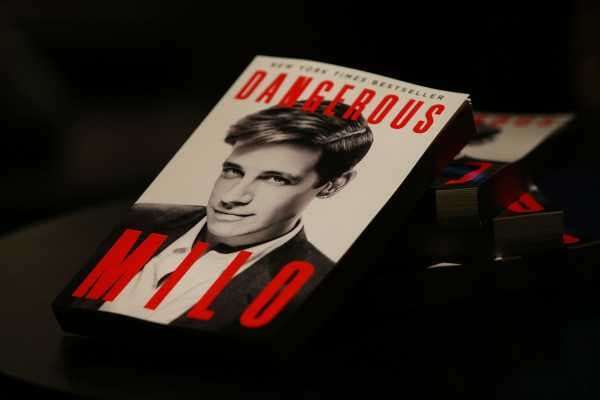

Milo Yiannopoulos is broke.

The provocateur, once one of the most prominent far-right voices in the country, lost his access to major conservative platforms in early 2017 after some comments that seemed to endorse pedophilia came to light. Without access to major publications and speaking engagements, he has entered a financial tailspin. Documents obtained by the Guardian showed that he was more than $2 million in debt as of October, $1.6 million of which was (inexplicably) owed to his own company.

Yiannopoulos confirmed his insolvency in a statement on his Facebook page, which includes pictures of him sipping a cocktail while wearing a T-shirt with the words “Broke Hoe” in big, bold letters.

“I was shocked to read more lies in the press about me today. They say I owe $2m. I don’t! It’s at least $4m. Do you know how successful you have to be to owe that kind of money?” he writes in the Facebook post.

Yiannopoulos openly concedes that his desperate financial situation — and that’s what this is, braggadocio aside — is the result of the concerted campaign against him by his opponents. “I am pretty broke, relatively speaking,” he says. “Two years of being no-platformed, banned, blacklisted and censored…has taken its toll.”

What this episode shows is that under the right circumstances, the controversial no-platforming tactics — which range from activists noisily disrupting speeches to big tech corporations banning provocateurs from their platforms — really can work. There’s no evidence that Yiannopoulos’s no-platforming led to his ideas and personality gaining a kind of underground popularity, as some free speech advocates believe happens when speech is repressed. Instead, they simply went six feet under.

But before Milo’s critics celebrate too much, they should be aware of the flip side to all this: The same tactics that can be used to repress awful speech can be used against speech that’s just unpopular or threatening to people in power. Today, no-platforming may shut down speech you don’t like. Tomorrow, it might threaten speech you do.

Now, that’s not to say no-platforming is an entirely illegitimate tactic. I think at times it’s justified against particularly vile speakers, and Yiannopoulos arguably fits the bill. It’s just that anyone who’s thinking about launching a no-platforming campaign needs to reckon with the inherent risks.

No-platforming works

You might think that Yiannopoulos’s flameout is an exception to the general rule of what happens to a no-platforming target. Part of his shtick was being ostentatious, flashing expensive jewelry and wearing absurd outfits. He was probably uniquely vulnerable to being cut off from the organized conservative movement and high-profile speaking engagements.

But he’s not the only noxious figure on the fringe right to suffer as a result of being no-platformed.

In August, key social media platforms — Facebook, YouTube, and Apple News — banned conspiracy theorist Alex Jones and his factually challenged site Infowars. Jones claimed after the banning that it would only make him more popular, that “the more I’m persecuted, the stronger I get.”

But a New York Times investigation published in September showed that this wasn’t actually true: In the three weeks following the ban, the average views of Infowars and Alex Jones videos examined by the Times fell by half. Two days after the Times published its investigation, Twitter permanently banned Jones from its platform, likely leading to an even steeper decline in access to his content.

This cutoff really threatens Jones’s bottom line. His profit model centers on selling medically dubious supplements to a mass audience, a lucrative business that brought in around $20 million in revenue in 2014 (the last year for which figures are readily available). If Jones is getting fewer people to buy into his worldview, he’ll have difficulty maintaining a mass audience for Infowars supplements.

And the Yiannopoulos-Jones story is typical, not the exception. Joan Donovan, a researcher at the Data & Society think tank who studies no-platforming, told Vice that her research finds consistent drop-offs in audiences after personalities are kicked off of social media platforms.

“Generally,” she explained, “the falloff is pretty significant and they don’t gain the same amplification power they had prior to the moment they were taken off these bigger platforms.”

There’s a reason far-right, anti-Muslim “journalist” Laura Loomer chained herself to Twitter’s Manhattan office doors last week to protest her ban from the service: It could very well lead to the end of her always-tenuous relevance.

The flip side of no-platforming: it can be used against anyone

But anti-racist activists aren’t the only people who can mount pressure campaigns against social media giants and university administrations that can veto speaking engagements. The right has a long and storied history of enforcing its own version of political correctness. According to one study, between 2015 and 2017, more professors were fired for left-wing political speech that offended someone than speech with a right-wing valence.

Just last week, CNN contributor and Temple University professor Marc Lamont Hill got in trouble for comments about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict that he made in a speech at the United Nations. The flashpoint was his call for “a free Palestine from the river to the sea,” an old Palestinian Liberation Organization slogan that’s typically understood as a call for the destruction of Israel.

Hill later clarified that he did not intend to justify killing Israeli Jews or to call for the forcible overthrow of the Israeli government, but the damage was done. Right-wing pro-Israel groups, alongside mainstream Jewish advocacy organizations like the Anti-Defamation League, condemned the comments almost immediately. Within 24 hours of the news breaking, CNN had fired Hill.

And the controversy didn’t end. This Monday, the chair of Temple University’s board denounced Hill, telling Philly.com that “free speech is one thing. Hate speech is entirely different,” adding, “We’re going to look at what remedies we have.” That’s one lost job for Hill already, and another potentially in jeopardy. The whole episode is strikingly similar to what happened to Yiannopoulos — some comments emerge that offend a large group of people, and a public figure’s access to major media platforms is in jeopardy or cut off.

Hill’s comments clearly aren’t as offensive as seemingly endorsing pedophilia, but there’s a debate as to just how bad they are. As a Jew with fairly left-wing views on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, it’s definitely not language I’m comfortable with. It really does echo calls for genocidal violence, and Hill should have been aware of that.

But it’s clear, at the same time, that Hill is not an equivalent figure to Yiannopoulos or Jones, who is famous principally for spreading hate speech and false conspiracy theories. Hill’s academic work has mostly focused on hip-hop and racism in the US, though he’s also done some research and advocacy on Palestine.

Yet he’s now at risk of facing a similar fate as those two provocateurs, being locked out of mainstream media and cut off from key sources of personal revenue.

Pressure campaigns really are effective at shutting down offensive speech. But no one has a monopoly on being offended — which means the more these campaigns spread, the more likely they are to curtail speech from people you agree with.

Again, that’s not to say no-platforming is never justified. I think Alex Jones’s ban from social media was a particularly clear case when removing a platform is a justified response. There’s no good way to stop the spread of fake news once it starts, and Jones’s entire raison d’être is spreading hateful conspiracy theories. Tech companies needed to draw the line somewhere, and it looks like Jones and Infowars were it.

But it’s not always that clear-cut. And the sheer power of no-platforming, the demonstrable ability to ruin media figures’ careers and thus have a chilling effect on controversial speech, suggests it should be used with caution.

Sourse: vox.com