The Medicare-for-all paradox

Passing single-payer means disrupting health insurance for 160 million people who get coverage through their jobs.

By

Dylan Scott@dylanlscott

Updated

Dec 16, 2018, 2:30pm EST

Share

Tweet

Share

Share

The Medicare-for-all paradox

tweet

share

Jessica Salfia knew the pay wasn’t going to be great when she became a teacher in Martinsburg, West Virginia, but she did have really good health coverage. She felt like she could go to see any doctor she wanted. The copay for an emergency room visit was just $15. She had three kids over the years, and health care was one thing Salfia didn’t feel like she had to worry about.

“The one thing about being a public schoolteacher was you knew that was taken care of,” Salfia, a teacher of 16 years, tells me. “But in the last four to six years, it’s been death by a thousand cuts.”

The state legislature kept cutting taxes, and copays for teachers kept going up — eventually costing Salfia and her family $100 just to show up at the emergency room or urgent care. On top of that, their health plan started to restrict which specialists they could see. Suddenly, some teachers had to travel as far as five or six hours to see a doctor.

Salfia’s daughter’s sore throat quickly spiraled into a $650 bill, as the rest of the family got sick. “My husband and I had to sit down and decide what bills we’re gonna pay or what bills we’re not gonna pay,” Salfia says.

The West Virginia teachers went on strike over rising health care costs, eventually securing a pay bump and a freeze on insurance premiums. But their plight reveals the cracks, increasingly difficult to ignore, in the bedrock of American health care: employer-sponsored insurance.

Half of all Americans get health insurance through their jobs. That’s by design. Doctors and hospitals in the mid-20th century saw a rash of government-run systems being set up in Europe and they lobbied hard to avoid one of their own, vastly preferring private coverage. Employee benefits were exempted from wartime price controls during World War II, giving employers an incentive to offer them at a time when it was nearly impossible to offer raises. Labor unions got on board too, sensing an opportunity to expand the safety net for workers without needing to pass another massive piece of social reform so soon after the New Deal.

But employer-sponsored insurance did not deliver a health care utopia. More than 30 million people still lack health coverage. Premiums and out-of-pocket costs for employer-sponsored plans have been rising steadily.

“Right now if you look at a lot of the labor disputes that go on, very often they have to do with health care. They have to do with employers saying, hey, you know what, we’re raising deductibles, raise your copayments,” Medicare-for-all proponent Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) told Vox in 2017. “What we can say to those workers is they will be better off financially and that their business that they work for will be better off financially.”

In a great historical irony, the evident faults of employer-sponsored insurance are helping fuel a new appetite for Medicare-for-all, a single-payer system where everybody gets health coverage from the government. But the work-based system, for all its flaws, could also be the biggest barrier to enacting single-payer. Shifting 160 million people from the coverage they currently get through their jobs to a new government plan is a lot of disruption — and disruption, especially in health care, makes a lot of Americans nervous.

If Medicare-for-all is ever to become more than a campaign slogan, its proponents must solve that riddle.

Ending work-based insurance is still a humongous challenge

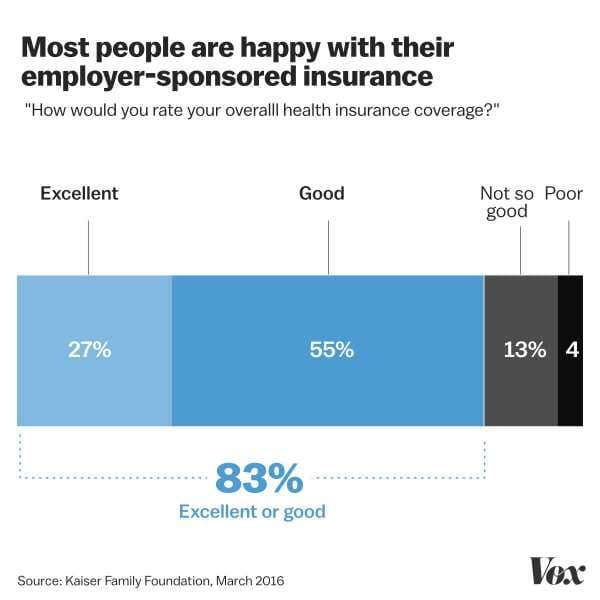

Medicare-for-all has become incredibly popular among the Democratic base, but the primary problem it will face is that many people are fine with the insurance they have today. They might not love it, but they are familiar with it, and for the people who don’t incur regular medical bills but want to be protected from an emergency, the benefits you receive through work-based insurance are probably sufficient.

“It’s a real barrier to doing anything big,” says John Holahan at the Urban Institute, who helped create a proposal explicitly designed not to disrupt work-based insurance. “Most people with employer plans are reasonably happy with them.”

When Vox conducted focus groups on single-payer, led by opinion researcher Michael Perry, one recurring concern we heard was from people who mostly like the insurance they have and were worried about losing it under Medicare-for-all.

“I wouldn’t like that,” Richard M., a federal official who gets his insurance through his work, said when told he would have to give up his insurance. “I like having an option. And I mean at this stage, I’m working full time, I should have an option.”

The polling bears out this sentiment: 83 percent of people with employer-sponsored insurance said in March 2016 that they thought their health insurance was excellent or good, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. The status quo is powerful in American health care — while there are problems, people are worried about big changes that could upend the system they rely on today.

Employer health insurance does do a few things quite well. It covers a lot of people, of course. It helps pool risk — companies, particularly larger ones, are almost by default a useful mix of healthy and sick people, helping to spread costs around, because they were not formed for the purpose of providing health insurance.

The price for insurance in the employer market has always been significantly less than buying insurance in the individual market. So its costs are lower, at least compared to what has been the alternative in this country for a long time, and people usually get pretty good benefits.

But Sanders and other stalwart single-payer proponents see health care as fundamentally different from other commodities and believe the government should guarantee health coverage. Their proposals would move every American out of private insurance and into a new government plan. (Supplemental private coverage would be permitted under Sanders’s bill, but the government’s benefits would be so generous that it’s hard to imagine much of a private market remaining.)

Medicare-for-all supporters argue the current system isn’t really working all that well anyway. Their evidence: Out-of-pocket costs are rising, millions of people are still uninsured, and yet America still somehow spends more money on health care than any developed country.

Other Democrats and left-leaning think tanks — cognizant of how deeply ingrained work-based insurance is in our health care ecosystem and of how allergic many Americans are to massive change — have introduced more incremental approaches, like Medicare buy-ins or a supercharged Obamacare that melds with Medicaid. Most of those plans would let private companies continue offering insurance.

Sen. Jeff Merkley, an Oregon progressive with stated presidential interests, co-sponsors Sanders’s Medicare-for-all bill — but he has also introduced his own narrower proposal with Sen. Chris Murphy of Connecticut to give people the option to buy a government plan.

“You have folks who will say, ‘Wait a minute, I don’t have a choice,’ and they will provide resistance,” Merkley tells me. “And, of course, the private insurance companies, which would be replaced, will put up massive resistance.”

The other argument made in favor of employer-based insurance is that it’s a constant experiment in how to better structure benefits and deliver health care. Hundreds of private companies are (the argument goes) constantly working to figure out how to offer insurance at a lower cost while still providing quality health care to their workers.

“A debate we’re constantly having is what’s the right way to cover the services we cover?” Paul Fronstin, who oversees the health insurance program at the Employee Benefits Research Institute, tells me. “My concern about moving away from the employer system is you lose that. Where does the innovation come from?”

But other experts are skeptical — they don’t see much evidence yet that employers are actually spending a lot of time or resources on these initiatives. “They haven’t proven that successful at improving health or managing costs,” Caroline Pearson, a senior fellow at NORC-University of Chicago, says. “What they’re investing in hasn’t shown any return yet. Behavior change is really hard. Frankly, we have no idea how to do it well.”

Salfia noted that the West Virginia school system tried to set up a wellness program at the same time as it was shrinking doctor networks and increasing copays. Teachers would be rewarded if they exercised or ate healthy or went to the doctor. They just had to wear a tracking device and upload the data to an online platform — in a state where many people still lack access to broadband Internet or cellphone service.

“The whole thing was crazy,” she says. The program was eventually dropped.

Employers are asking employees to pay more money for health care

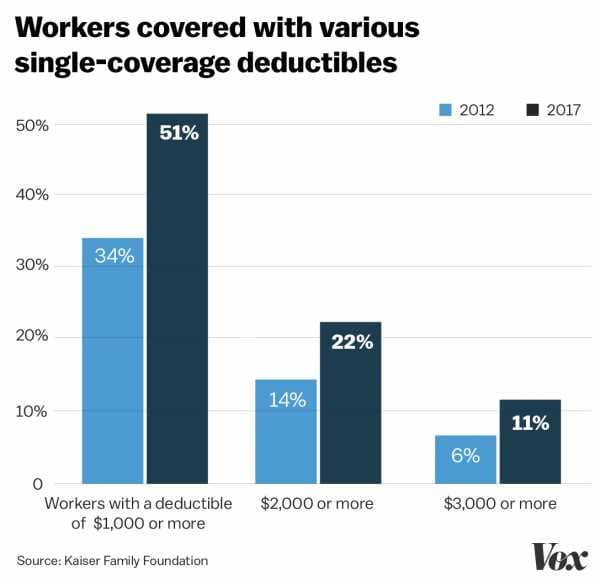

What happened in West Virginia isn’t that different from what’s happening in companies across the country. As health care costs rise, workers over the past decade have been asked to pay more and more money out of their own pockets, as their businesses shift toward less generous benefits.

“Our system is a policy disaster. If there weren’t some strong locked-in features of our system, nobody would accept it,” says Jacob Hacker, who studies health policy at Yale University. “It’s a great system when people had something closer to lifetime employment and employers were providing good benefits, but it’s a really crappy system when that’s not true.”

The percentage of workers with a deductible of more than $1,000 has increased significantly, from 34 percent to 51 percent since 2012, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

“When times are tough, employers start to cut back on the generosity of their benefits,” Fronstin says. “Deductibles go up. People are paying more money out of pocket.”

The foundation of our work-based insurance system — that health insurance benefits are tax-free to companies and workers — also makes the problem worse.

The economics are pretty straight-forward: Employers save on taxes when they spend money on health care instead of wages. They provide more generous insurance than they would if benefits were taxed and because the benefits are more generous, employees use more health care.

“That makes health care more expensive and makes the health care market bigger,” says Austin Frakt, a health economist at Boston University.

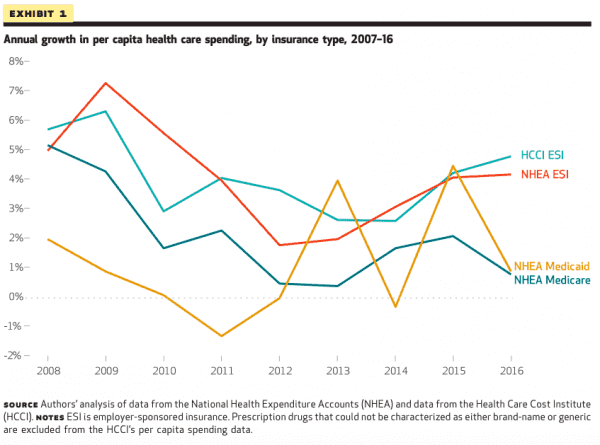

Health care spending for job-based insurance increased by 44 percent from 2007 to 2016, according to researchers at the Health Care Cost institute. Its growth rate was consistently higher than that of Medicare or Medicaid, the major government insurance programs.

Making matters worse, from a left-leaning economic perspective, the current system favors large employers and higher-income employees.

“The higher the tax bracket of the employee, the bigger the subsidy, which accounts for hundreds of billions of dollars each year,” Stanford University’s Victor Fuchs wrote in JAMA recently. “Perversely, most of the tax subsidy is received by employees with above average incomes.”

This is the opening for single-payer supporters: While you might be used to the health insurance system we have now, it isn’t nearly as good a deal as you might think it is and a single-payer program would be more equitable.

A surprising number of Americans might be persuaded by the argument: Kaiser found in June 2018 that 20 percent of people with work-based insurance said they’d had problems in the past year paying their medical bills. Just because you’re technically covered doesn’t mean you can’t face onerous medical bills. Medicare-for-all offers a coverage guarantee and eliminates out-of-pocket costs.

One development to watch is whether businesses themselves come to decide that they might be better off under single-payer. This is an argument that I’ve heard from Medicare-for-all supporters who won House races this year, like Katie Porter in Orange County, California. It’s also an argument that Sanders, the godfather of single-payer, has made.

Companies have found it worth their while to offer insurance for the better part of a century. Good benefits help attract good workers. The benefits are tax-free. “They’ve felt there was a lot of value for them to offer it,” says Fronstin.

But these days, the cost of covering workers is going up for companies — the average employee contribution rose from $3,300 in 2007 to $5,700 in 2017, but the average employer cost also went up, from $8,800 to $13,000 — and administering health care benefits requires staff, time, and money.

Companies are at least starting to ask the question, Fronstin says: “Are we doing better than Medicare-for-all?”

“That’s the thing they have to wrestle with,” he adds, “which they’ve never really had to wrestle with before.”

Should your employer really determine your health insurance?

One of the promises of Obamacare was that it might loosen the ties between work and health coverage. It hasn’t. Some people see that as a sign of the current model’s strength.

“There’s no indication that the employer market is at a breaking point,” Pearson says.

When President Obama and Democrats in Congress settled on a health care plan, they largely left big employer plans alone. That was a political calculation, but Democrats still reaped the whirlwind of more than 4 million canceled insurance plans that didn’t meet the new standards they set. Transitioning to single-payer in the near term requires canceling plans for 160 million people.

Work-based insurance is so untouchable that, though economists to the right and left agree its tax benefits should be limited, both Democrats and Republicans ended up ducking the issue when it came time to actually pass a health care bill. The ACA’s ‘Cadillac’ tax on high-end insurance plans, a different means to similar ends, has never actually been enforced; Congress has, on a bipartisan basis, repeatedly delayed it. House Republicans caved with just the whiff of industry pressure in 2017, quickly pulling such a provision from their plan.

Single-payer supporters see this as another failure of the ACA and the need for more ambitious reforms. They condemn a system that tethers people to their jobs, even if they don’t like them, strictly so they can hold on to their insurance.

“You also talk to people who say, ‘You know, I really don’t like my job, I really hate my job, but I go to my job because my wife is ill and I have to make sure that I have good coverage to take care of her.’ Is that a way to run an economy?” Sanders told Vox. “So there are a lot of reasons why I think we need to do what virtually every other country has done, and get private insurance companies out of the essential health care.”

There is a foundational question here, one often lost in debates about premiums and health care expenditures and uninsured rates or rates of growth: Should your employer be allowed to decide what kind of health insurance you have?

The Trump administration has recently relaxed the ACA’s requirement that all insurance plans cover contraception, allowing even major Fortune 500 firms to refuse to cover birth control over any religious or moral objection.

One anti-abortion Christian woman told the Senate Judiciary Committee during the Brett Kavanaugh Supreme Court hearings about how her faith-based health plan, contracted through her church-affiliated employer, refused to pay for her IUD. She and her husband cut back on their student loan payments to cover the $1,200 bill.

“I have experienced firsthand what it is like to struggle to afford birth control when someone else’s religious beliefs deny it to you,” Rev. Alicia Baker Wilson told senators earlier this year.

Single-payer skeptics talk a lot about freedom and choice, which they say would be lost under Medicare-for-all. Many Americans seem to genuinely share those concerns.

But there should be no illusions: Your freedoms can also be compromised when your employer decides how much you must pay for health care or what kinds of medical services you can get covered.

As Jacob Hacker put it, drawing on the language so often deployed by Medicare-for-all supporters: “Our system will not create health care as a right.”

Sourse: vox.com