The Netflix true crime docuseries Making a Murderer returns for a second season on Friday, October 19, providing a fresh look at developments in the murder case that captivated so many during its first season.

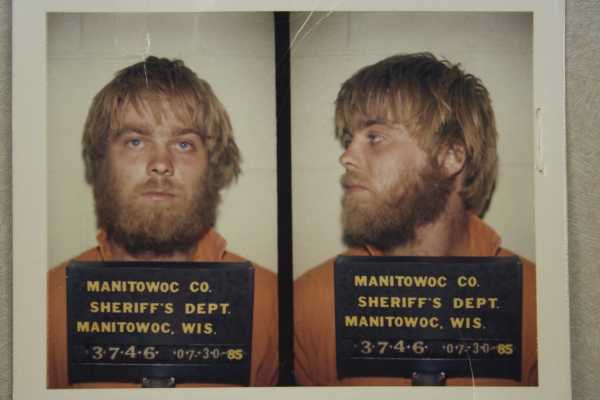

The show, which quickly became a big hit after it debuted in December 2015, dug into the criminal cases of Steven Avery and his nephew Brendan Dassey, both of whom were sentenced to life in prison in Wisconsin for the 2005 murder of Teresa Halbach. The second season will look at what’s happened since the first originally premiered.

Season one of Making a Murderer strongly suggested that Avery and Dassey were framed — that evidence was planted, and that police manipulated Dassey in particular into confessing to crimes that he, the show implied, didn’t commit. It built a lot on a previous false conviction against Avery for an attack in 1985 that DNA evidence would later show he was wrongly accused of.

In this, the first season painted a picture of a criminal justice system that was more interested in protecting itself — particularly from a lawsuit and the embarrassment that came out of the 1985 false conviction — than protecting the people the system is meant to serve. That, unsurprisingly, drew a large response on social media, with people objecting to the way Avery was treated.

The show also gave people a chance to play detective on their own. Lots of debates came about after the show’s release — about whether Avery was guilty, whether the show really presented all the important evidence, who could have been Halbach’s killer if Avery was not, and more. As is typical for true crime series, the show couldn’t and didn’t answer all these questions, leaving a lot of room for viewers to figure it out for themselves and talk to others about it.

At the same time, the first season was heavily criticized for leaving out some evidence that made Avery and Dassey look worse — raising questions about what dramatic liberties, as a TV show, the series took to preserve its overall narrative. While Making a Murderer’s creators answered some of those questions on social media, the second season now offers them a chance to not just look at what happened since the first season came out but also to address the lingering concerns.

All of this — the horror at the criminal justice system’s failures, the room for speculation and debate, and other arguments about what the show left out — culminated in a massive hit for Netflix that drew a lot of attention in the months after it was released.

Making a Murderer’s first season captivated audiences

The initial 10-episode run focused largely on Avery. He was originally convicted in 1985 of trying to rape and kill a woman, but DNA evidence exonerated him 18 years into his imprisonment — and, as the documentary shows, there were several mistakes made in the investigation.

These mistakes are crucial to Making a Murderer’s look at Avery’s second murder conviction in 2007. By showing that Manitowoc County officials and investigators overlooked pieces of evidence that could have exonerated Avery early on (including overlooking a suspect who was actually under surveillance and was later convicted of sexual assault), the documentary established early on that these officials were potentially incompetent or, perhaps, were motivated to go after Avery after he had embarrassed them and filed a lawsuit against them over his first wrongful conviction.

Building on these mistakes, the series questioned Avery’s second conviction. It focused a lot on the DNA evidence that linked Avery to the murder, suggesting that it was planted. It also played video of investigators’ interrogation of Dassey, which suggested that he was manipulated into confessing. In doing so, the series not only raised questions about Avery and Dassey’s innocence, but also about how easy it may be in the American criminal justice system to, well, make a murderer out of an innocent person.

That concern — that anyone could be framed in this way, especially twice — propelled discussions all over the internet about how outrageous Avery’s conviction was, what the show got wrong, what it missed, and the unanswered questions. It made the series a huge success when it first premiered on Netflix.

Netflix does not typically release viewership numbers. And some of the estimates out there suggest that Making a Murderer probably didn’t succeed in numbers of viewers in the same way that, say, Fuller House, Gilmore Girls, or some of the streaming network’s Marvel shows have.

Where Making a Murderer did succeed, though, is in owning the conversation on social media. As Paul Tassi wrote at Forbes at the time, “I have never seen a show consume the pop culture conversation like this outside of when programs like The Walking Dead and Game of Thrones kill off a major character.” (To this point, the Vox explainer I co-wrote with Alex Abad-Santos for the first season is still one of my most widely read articles.)

One reason for all the conversation was the show’s big moments and how it slowly teased out huge reveals in the same way a fictional drama might.

For example, the blood vial. One of the most significant pieces of evidence against Avery is that his blood was supposedly found in Halbach’s SUV (which was found on the Avery family’s property).

But in the documentary’s biggest moment, Avery’s lawyers reveal that the blood may have come from a vial of blood taken from Avery during his 1985 case. The big reveal shows that the evidence box that contained the vial was cut open, and that there was a puncture the size of a hypodermic needle in the vial’s top — something the county lab says it didn’t and wouldn’t do. As a viewer, it was a moment as dramatic and shocking as a Game of Thrones plot twist.

Beyond the major moments, the show also created a lot of room for debate. While it poked holes in the case against Avery and Dassey, it didn’t exactly give satisfying conclusions to some of the lingering questions — like who really killed Halbach if it wasn’t Avery or Dassey.

The show also raised questions about some of the finer details of the Avery case. Why was the key to Halbach’s SUV only found after multiple searches, and why did it have only Avery’s DNA but not Halbach’s, even though Halbach would have used the key for years? How did police find a bullet with Halbach’s DNA on it in Avery’s garage, but no other DNA evidence — not even the slightest traces of Halbach’s blood — in the same garage? Why did police find some of Halbach’s bones right outside of Avery’s home, but also some of them scattered through the Avery family property? Why would Avery move only some of these bones, and why would he move them to other parts of his family’s land, of all places?

All the questions posed by the case are made believable by the puncture in the old blood vial. If it’s believable that police may have planted Avery’s blood in Halbach’s car, what else would they have been willing to do? Plant a key? A bullet? Bones? The documentary pushed on this kind of questioning to build reasonable doubt in the audience’s mind, much like a good defense lawyer would for a jury. But it also left a lot of room for discussion and speculation.

Finally, the prosecution built much of its initial case on Dassey’s testimony. The prosecution announced Dassey’s supposed confession in a big press conference, implying that Dassey had provided a highly detailed account of what happened. But video of the confession later suggested that investigators manipulated Dassey, who was 16 at the time and may have a cognitive disability, into confessing with leading questions. Once Dassey lawyered up, he withdrew his confession, and the prosecution didn’t use it in Avery’s trial due to its very questionable nature.

This added yet another layer of outrage — and reason to doubt what police claimed about Avery.

And more broadly, the show provided an opportunity to discuss America’s criminal justice system. If Avery really is innocent, just how reliable is this system that is charged with incarcerating people, potentially for life, and even executing them? And what could that mean for anyone who’s caught by the system, including, perhaps in the future, the viewer?

Making a Murderer was criticized for leaving some things out

The broader discussion about Making a Murderer also led to criticisms — particularly, that the series left out some evidence.

Ken Kratz, the state prosecutor who led the case against Avery, became very vocal, talking to publications like Maxim, People, and the Wrap to recount key facts that he claimed were purposely excluded from the series. (He is also now taking part in a separate documentary series about the Avery case called Convicting a Murderer.)

Kratz claimed that the series glossed over Avery’s alleged animal cruelty. He also said it excluded DNA evidence, besides blood, that was supposedly found in Halbach’s SUV. And Kratz said the series overlooked the ballistics testing that supposedly tied the bullet found in Avery’s garage to Avery’s own rifle. (These are just some examples. For a more thorough breakdown of the missing evidence, read Vox’s original explainer.)

The show’s creators, Laura Ricciardi and Moira Demos, later responded to some of the claims on Twitter and in interviews. They argued that what was excluded from the show was, generally, evidence that wasn’t important to the trial or was actually excluded from the trial because it was so weak.

From an entertainment standpoint, this is understandable. Making a Murderer simply couldn’t show every moment of footage from Avery’s trial, every single quote from the people who were interviewed, or every single detail of the case. If it had, it would be tremendously boring and hundreds of hours long. Some cuts had to be made somewhere.

The series’ creators have also emphasized that their goal was to highlight not just the problems in Avery’s case but also the broader flaws in the criminal justice system. In that latter sense, the show was a success: At the very least, it shows that Manitowoc County law enforcement officials were very shoddy, if not malicious, in their work — leading to, at a minimum, one wrongful conviction. If that can happen anywhere in America, it points to a big flaw in at least part of the criminal justice system.

Still, some of the questions about the specific details of Avery’s case linger. With a second season, Making a Murderer gets another chance to address the concerns.

A lot has happened since Making a Murderer came out

Since the first season of Making a Murderer came out, there have been some developments in Avery and Dassey’s cases. The first trailer for the second season teases some of that news and how the second part of the series will cover them.

The trailer started with Avery’s reaction to the wave of responses he’s gotten to the first season. (“I didn’t think all of these people would care,” Avery said.) It also hinted at the developments in Avery’s case, like prominent Chicago lawyer Kathleen Zellner joining the defense. And it teased potential new evidence that could help Avery overturn his 2007 conviction.

That’s only the tip of the iceberg of what the show could cover. A lot has happened in the three years since Making a Murderer’s first season.

Here are the major developments in Avery’s case, based largely on continued reporting by the Appleton Post-Crescent in Wisconsin:

- January 8, 2016: Zellner joined Avery’s defense, along with the regional Innocent Project’s Tricia Bushnell. Zellner has 19 exonerations to her name.

- August 26, 2016: Zellner filed a motion for additional scientific testing.

- June 7, 2017: Avery’s defense filed a motion for a new trial.

- October 3, 2017: Sheboygan County Judge Angela Sutkiewicz denied Avery’s motion for a new trial. (A Sheboygan County court was put in charge of the case to avoid a conflict of interest, given Avery’s allegations against Manitowoc County officials.)

- November 28, 2017: Sutkiewicz again denied Avery’s motion for a new trial, following Zellner’s request that the judge rethink her decision.

- June 7, 2018: The Wisconsin Court of Appeals remanded Avery’s case back to Sutkiewicz, asking the lower court to address whether a CD — which Zellner argued was kept from Avery until April but contains exculpatory evidence — can be submitted into the record.

- September 6, 2018: Sutkiewicz denied the motion to add the CD to the record, effectively blocking, once again, a new trial. Zellner said she will appeal the decision.

Here are the major developments in Dassey’s case:

- August 12, 2016: A federal judge overturned Dassey’s conviction — declaring that Dassey’s constitutional rights had been violated and that investigators had manipulated him during questioning. It was, at least for the moment, a huge victory for Dassey, but he remained in prison while the ruling was appealed.

- June 22, 2017: A Seventh Circuit Court panel upheld the lower court order overturning Dassey’s conviction.

- December 8, 2017: After the case was appealed to the full Seventh Circuit Court, the court narrowly ruled against Dassey, leaving his conviction in place. The court’s dissenting judges called the decision “a travesty of justice.”

- February 20, 2018: Dassey’s defense appealed the case to the US Supreme Court.

- June 25, 2018: The Supreme Court declined to hear Dassey’s appeal — ensuring with near certainty that he’ll have to serve his life sentence, with eligibility for parole in 2048, unless his lawyers can convince a judge that there’s compelling new evidence in the case.

The second season will likely cover these events. But it also may get into more: Will it present new evidence in either case that’s not currently known to the public? What will it say about Dassey now that his fate seems set? What will it show about how the lives of Avery, Dassey, and their families have been affected by all the attention due to the documentary?

Waiting for these answers feels a bit like waiting for just about any other TV show on Netflix. But that’s kind of the point; it’s what makes true crime series, from Serial to all those shows on the History Channel, so captivating. They dramatize real-life topics and events that are deadly serious, including murder, with the same flair that you would expect of a fictional TV show like Dexter or The Walking Dead. But by using real-life events, these shows can also up the outrage and need to discuss what’s happening with others — since what’s depicted can, at least we’re often led to believe, happen to any of us.

So we wait for a conclusion to the storyline, or at least some answers, just like we would for other TV shows. With Friday’s second season premiere, we might get that. But maybe not — and we’ll end up filling the void with a lot of chatter on social media.

Sourse: vox.com