Despite an opioid crisis, most ERs don’t offer addiction treatment. California is changing that.

This is what it looks like when we stop treating addiction as a moral failure.

By

German Lopez@germanrlopez

Updated

Jan 8, 2019, 11:25am EST

Share

Tweet

Share

Share

Despite an opioid crisis, most ERs don’t offer addiction treatment. California is changing that.

tweet

share

Finding the best ways to do good. Made possible by The Rockefeller Foundation.

Part of

Confronting America’s opioid epidemic

SACRAMENTO, California — When Michael Curci still used opioid painkillers and heroin, he didn’t see himself living beyond his mid-20s.

“I didn’t even think I was going to make it,” Curci told me, while at the El Dorado County clinic where he receives treatment for opioid addiction. “I didn’t think I was going to have any type of future.”

Curci is now 28. The moment that helped him survive came in October 2017, when he went to an emergency room not due to an overdose or an injection-related infection but to seek treatment for addiction. Unlike most hospitals in the US, Marshall Medical Center, an hour’s drive east of Sacramento, provided him with real treatment — particularly, buprenorphine, a highly effective medication that treats opioid addiction by mitigating withdrawal and cravings for the drugs.

For Curci, the approach has worked — after years of drug use, parties, doctor-shopping to get painkiller prescriptions, and even prison time due to two robberies meant to help get money for more drugs. There have been setbacks and one brief relapse since Curci got into treatment, but “now I know I’m going to have a future,” he said. “Now I know that I can do these types of things. I can have a job. I can do whatever I want with my life.”

If Curci had gone to the emergency room at most other American hospitals, his story might have ended differently. Patients in ERs with other chronic conditions, like heart disease or diabetes, typically meet with a specialist quickly to start the long-term process of managing their condition. A patient with drug addiction, on the other hand, is often sent on his way with a pamphlet for treatment options, a few talking points, and not much else — even though the evidence suggests that this hands-off approach does little to reduce the serious risk of overdose and death.

Curci, though, encountered a still-unusual approach of treating addiction in the emergency room — one that California, Massachusetts, and other states are now expanding in earnest as the country deals with an opioid epidemic.

At the core of this work is a straightforward idea: treating addiction like any other medical condition, and building treatment for addiction into the rest of the health care system.

If done right, this idea could dramatically expand access to addiction treatment across the US. Instead of relying on expensive, infrequent, and siloed addiction treatment facilities, people with addiction could go to their doctor or local hospital to get help. They could pay for that treatment not out-of-pocket — as remains common — but with health insurance, making treatment much more affordable. The medication they use would be viewed not as a crutch — a common view of buprenorphine — but as akin to insulin, aspirin, or any other medication for chronic conditions. And as with other conditions (from diabetes to cancer to heart disease), relapse wouldn’t be treated as a moral failure, but a normal part of recovery.

The ER is one place where this broader approach can begin. Most emergency rooms across the country, though, do not offer this care. Much of that is caused by stigma toward drug use and addiction, which can make it difficult to persuade ER doctors to do something they historically haven’t done. But even if health care providers do want to offer addiction treatment, there are concerns: How do you do it? Will it be expensive? Where will patients go for continuing care after they leave the emergency department, especially in a country where treatment options are often inaccessible or nonexistent?

California and other states’ experiences, though, suggest an ER addiction treatment program isn’t only possible, but that it works. California is now gearing up to expand the idea, with the state’s Bridge Program and Public Health Institute gearing up to award more than $8 million to as many as 30 hospitals in the coming weeks. By making treatment more like other kinds of health care, the state is hoping to see more stories like Curci’s.

As America’s opioid epidemic continues, the approach is increasingly necessary. Drug overdoses were linked to a record 70,000 deaths in 2017, more than two-thirds of which involved opioids, and 2018 appears to have been about as bad. And beyond the overdose deaths, federal surveys have found that there are more than 2 million people addicted to opioids in the US — and experts say that is, if anything, an underestimate. Those are millions of people who could potentially benefit from treatment if it’s made more available.

Filling America’s addiction treatment gap

Most people in the US with drug addictions struggle to get treatment. A 2016 surgeon general report found that just 10 percent of people with a substance use disorder get specialty treatment, in large part due to a lack of access to care. Even when specialty treatment is available, federal data indicates that fewer than half of treatment facilities provide evidence-backed medications like buprenorphine or methadone.

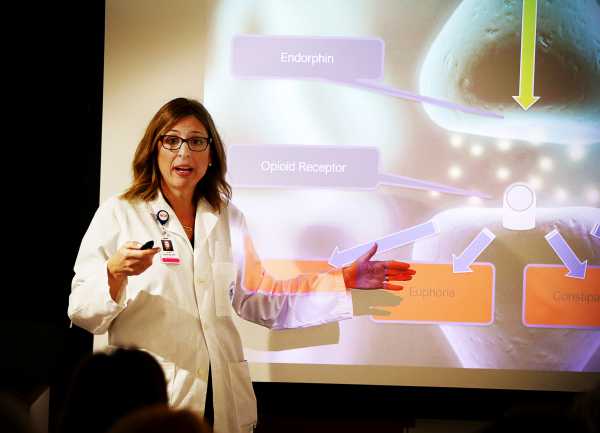

These medications have been around for decades. Studies show that they reduce the all-cause mortality rate among opioid addiction patients by half or more and do a far better job of keeping people in treatment than non-medication approaches.

But misconceptions remain about buprenorphine and methadone, in large part because they are opioids themselves. Curci himself told me that he worried the medication was just “substituting one drug with another.” But the problem with addiction isn’t that someone is using drugs or even opioids. The problem is when drug use turns compulsive and harmful, leading to health problems, broken relationships, crime, and other negative consequences. So if buprenorphine or methadone helps someone stabilize his life, as was true in Curci’s case, then the medications really do treat the addiction even if they’re taken indefinitely.

But as the federal data indicates, these medications remain difficult to get in America.

In theory, health care providers can prescribe buprenorphine, but not many do. According to the White House opioid commission’s 2017 report, 47 percent of US counties — and 72 percent of the most rural counties — have no physicians who can prescribe buprenorphine. Only about 5 percent of the nation’s doctors are licensed to prescribe buprenorphine. And if a health care provider does want to get certified, the process can be time-consuming — requiring, under federal law, a special training course that’s eight hours for doctors and 24 hours for nurse practitioners and physician assistants.

Methadone is similarly inaccessible. It’s siloed off into special clinics, which face arduous federal, state, and local regulations, and are frequently forced to operate in low-income and minority neighborhoods due to not-in-my-backyard attitudes. Many places don’t have any methadone clinics at all — including El Dorado County, where Curci got help at Marshall.

Traditional addiction treatment clinics can also offer the medications, but, based on the federal data, the majority don’t. That’s a result of the kind of stigma Curci previously held: Despite the evidence of effectiveness, many traditional addiction treatment programs don’t see people as genuinely in recovery if they use buprenorphine or methadone.

The opioid epidemic, however, has led policymakers and people in addiction treatment to reevaluate the evidence and to try to dramatically expand access to addiction treatment. That’s now extended to ER-based solutions.

The idea is not that someone has to come into the ER through an overdose or injection-related infection to start getting into treatment. As Arianna Sampson, who helped set up the ER program at Marshall Medical Center, told me, the possibility of withdrawal — which is characterized by terrible flu-like symptoms, along with crippling anxiety — is enough of an emergency to start getting people into treatment. In short: If someone wants help, they can get it at the ER 24/7.

“We have an open door,” Sampson said.

Seeking help at the ER

One patient, whom I’ll call Claire, went to the the UC Davis Medical Center in Sacramento in withdrawal and wanted to start on buprenorphine for her opioid addiction. At 48, Claire had most recently been using opioids for five years, though she had struggled with drug use for much of her life.

Claire carried around a large bag, which, among other items, held phones that she played games on to distract herself from the withdrawal pain that she was currently going through. Asked where she felt the pain, she responded, “Everywhere.” On a scale of 1 to 10, she rated her pain an 11.

Claire found out about the ER program through its substance use counselor, Tommie Trevino. But when she showed up, she was skeptical it would work. “I’m in withdrawal,” she said. “I’m scared it’s not going to be enough.”

The UC Davis ER staff checked her vital signs and asked her about her previous medical history, which included pancreatitis, hepatitis C, and a fractured back. They asked when she last used heroin, since buprenorphine requires at least partial withdrawal to work. Claire said she had last used at 8 pm, a bit over 14 hours before she showed up at the ER. That’s enough time for withdrawal.

In between doctor and nurse check-ins, Claire opened up to Trevino about struggling with addiction, an abusive husband, and better times before she fell down into heroin use once again. She complained about the withdrawal pain, which she said was causing her to hurt all over her body. She talked about her 5-year-old granddaughter. “She’s my life,” Claire said. She joked, “I don’t even like my kids anymore.”

A nurse gave Claire a first dose of buprenorphine, then, when it wasn’t enough (which is pretty typical), another dose. Within an hour, Claire was relaxed. Her heart rate calmed. When she first came in, Claire was restless and in pain, refusing food because she was nauseated from withdrawal. Now she could sleep. She said she was hungry and got a sandwich shortly before she left.

“That stuff works pretty fast,” Trevino said.

By the time Claire left, she had begun setting goals for her recovery and said she felt “great” and was “grateful” for the chance to get treatment.

There is growing evidence for the ER approach

Watching the ER visits, the most striking thing about them was how normal they were and how much the clinicians involved simply treated addiction like any other health problem. Patients had their vital signs taken. Doctors and nurses checked for other medical needs. Patients got other care as necessary. The discussion about addiction, too, seemed largely like any other doctor’s visit — with a back-and-forth about the patient’s problems and desires, and how that could be balanced out with what the health care provider considers best.

This is not how America has, by and large, confronted addiction in the past. Addiction has notoriously been characterized as a moral failure. The most common response I get to any addiction story argues that overdoses are just “Darwin’s theory in action.”

A growing body of scientific evidence, though, shows that this has never been the right way to approach addiction, and addiction should instead be treated much like the ER visits that I witnessed.

One big study, published in JAMA in 2015, randomized participants at Yale New Haven Hospital in Connecticut into a more typical ER approach for addiction that referred patients to treatment elsewhere, another approach that tried to more directly motivate patients to seek treatment, or buprenorphine treatment. A month in, the patients who got on buprenorphine treatment in the ER were around twice as likely to remain in addiction treatment compared to other participants, and reported less than half the days of illicit opioid use per week as the other groups.

A follow-up study published in Addiction in 2017 also concluded that buprenorphine treatment is cost-effective compared to other approaches.

One hitch to the initial study: While buprenorphine patients reported less illicit opioid use per week, all patients — regardless of approach — were about as likely to test positive for opioids in urine tests.

Gail D’Onofrio, lead researcher on the study, argued that this doesn’t mean that the buprenorphine treatment was less effective, because urine tests can pick up opioid use from days ago. So if someone has reduced their opioid use but is still using to a lesser degree — still a welcome, if imperfect, development — that wouldn’t show up with a urine test, but it would in the self-reports.

D’Onofrio did caution, though, that the study’s promising results don’t necessarily mean that the ER approach will work everywhere. Yale’s hospital, which is highly respected and connected to a lot of local treatment resources, may be able to do this kind of work better than most others. (Even the standard, referral-only approach that the study used was more extensive than what most ERs do.) The same might not be true in other parts of the country.

So research will likely need to validate the approach in other areas. Some of the people involved in California’s work — along with the National Institute on Drug Abuse, a federal agency — are working to produce those studies. But there’s good reason to think it’ll work, given the Yale study and the overall evidence behind buprenorphine.

Treatment is needed after the ER, too

The hardest part of getting addiction treatment in the emergency department may not be anything in the ER itself. Instead, leaders of ER programs in different states told me that the biggest hurdle may be ensuring that a patient has a place to get longer-term care after the ER starts that patient on addiction treatment.

At the UC Davis emergency room, Claire left with a buprenorphine prescription to tide her over, and staff set up an appointment with a county clinic for low-income patients like her that can usually see new patients within a week.

It was, Trevino told me, the typical process: A patient comes in with withdrawal, overdose, or an injection-related infection; gets started on medication treatment; and is set up with another health care provider for longer-term care.

A bit east, at Marshall Medical Center, it was the same process that Curci went through when he was referred to El Dorado Community Health Centers, where he’s still a regular patient. It’s what anyone would expect from the ER with any other medical condition.

But longer-term care is a thorny problem. Even if an ER starts people on addiction treatment, it’s possible, even likely, that there won’t be a treatment clinic around, or a clinic will have a waiting period of weeks or months. It’s the equivalent to having the ER stabilize someone with a heart attack and giving them some short-term medication, but there being no cardiologists or other specialists around for follow-up care.

This is one of the most common concerns that ER health care providers raise about offering addiction treatment, said Sarah Wakeman, an addiction doctor and the medical director at the Massachusetts General Hospital Substance Use Disorder Initiative. As Massachusetts, one of the states hardest hit by the opioid crisis, has enacted legislation to get more ERs to do opioid addiction treatment, a lot of its focus has gone to making sure there is a source for follow-up care. But the process of rolling out this legislation and related programs hasn’t been easy.

“It was a tough sell to get the emergency medicine doctors interested in or excited about getting waivered for buprenorphine without knowing what would come after the ED,” she explained.

Overcoming that hurdle has required linking existing addiction treatment providers, who needed to coordinate with each other to work more efficiently and take in more patients overall. But in some cases, the existing pool of providers wasn’t enough, so new clinics or providers had to be established from the ground up.

In California, the same concerns were raised. Much of the work in Sacramento has focused on simply finding more addiction treatment providers and clinics to follow up with patients, said Aimee Moulin, who’s helped set up the ER program at UC Davis Medical Center.

One of the clinics the ER partnered with in Sacramento, Transitions Clinic, has an incredible backstory: Its founder, Neil Flynn, was on the front lines of HIV/AIDS during the height of that epidemic in the 1980s and ’90s. As he saw some of his HIV patients get addicted to opioid painkillers and as the opioid crisis worsened, he moved to the front lines of another epidemic, got certified to prescribe buprenorphine, and began treating addiction.

When I asked what buprenorphine treatment had done for them, patients at appointment after appointment at Transitions all said the same thing: “It changed my life.” They told me about how now they could attend to their families, maintain a job, and get back to other interests. One patient was very excited she had been hired for a voice acting gig for a major video game company.

But all this came at a steep cost for patients: $200 per month. Transitions does not accept insurance.

The $200 a month paid for as many appointments as patients needed. When I was there, Flynn often told someone to come for a follow-up a week later, free of charge. But it still came down to $200 a month, completely out of pocket.

If he took insurance, Flynn said, there’s a good chance that his clinic — which was barely breaking even, he emphasized — would actually lose money, because health insurance didn’t pay much, and he’d have new expenses, such as hiring staff for billing and working with insurance companies. That’s a common problem with addiction treatment, for which insurance reimbursement rates are often low.

But $200 a month is a lot to ask for, particularly for people with opioid addiction who may not have been able to keep a job due to their illness. The good news is insurance will pay for the buprenorphine itself when a patient goes to pick it up at the pharmacy, but that doesn’t cover the other expenses.

Moulin and Trevino acknowledged the problems with Transitions. But they noted that Transitions had a big advantage: It could take patients within a couple days. The other partner that UC Davis worked with, a county clinic, did accept insurance, particularly Medi-Cal (California’s equivalent of Medicaid), but it typically could only see patients after a wait time of a week. Claire, as someone who’s jobless and on Medi-Cal, had to go to the county clinic.

This is the difficulty of finding partners, particularly in rural regions but even in some well-resourced areas like Sacramento: The options can be so scarce that pros and cons have to be worked around, with providers left hoping that someone or something else — like, say, a federal infusion of funding — will help finally solve the underlying problems that lead to too few addiction treatment providers.

Wakeman argued for another solution: getting more traditional health care providers certified to prescribe buprenorphine. Under federal law, doctors, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants can obtain a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine. But it requires a special training course, meaning health care providers must be committed to doing this. If they do it, though, they could help dramatically expand access to opioid addiction care.

The integration of addiction treatment into health care

At the core of all the ER work is a straightforward idea: treating addiction like any other medical condition and building treatment for addiction into the rest of the health care system.

When I asked Moulin how she saw her own role in California’s ER program, she responded, “At the heart of it, I’m just an ER doctor.” This is how she wishes other people saw this work: that treating addiction is simply part of the job of working in health care.

The major hurdles to accomplishing that, Moulin and others told me, are a mix of stigma, misconceptions about addiction, and institutional inertia.

The modern understanding of addiction stresses treating addiction as a medical condition, with social and environmental contributors. But even among doctors, it’s still very common that people perceive addiction not as a medical condition, but as a moral failure. Some health care providers also question why they should care about addiction, given that they typically haven’t had to in the past. Both biases can be overcome with education — but they are lingering problems.

Other providers worry that treating addiction will cause patients with substance use disorder to flood their offices and clinics. But this, D’Onofrio of Yale said, misunderstands the reality: “They are already in your ED, because they’re there with withdrawal or other complications. … In fact, you got a good chance you’re going to reduce your ED visits once you get them into treatment.”

Another problem that Moulin pointed to is a widespread belief that opioid addiction is untreatable. A lot of news coverage focuses on the dire statistics about opioid addiction, but not solutions — leading many to think that the situation is grim and unsolvable. ER doctors also often see patients with addiction come back after multiple overdoses; that, over time, makes them jaded about whether these people are actually getting better.

But treating addiction also requires acknowledging that setbacks can happen and are even common. After Curci’s first visit to the emergency room that got him into treatment, he entered a 90-day residential program. Once he got out, he got a job, a car, and his own place to live — all things he could never hold onto before. But a few months in, Curci said, he messed up — letting his ex-girlfriend, who was using heroin, back into his life. That led to a relapse.

Relapse is common for all sorts of chronic conditions, from cancer returning after remission to a sudden depression episode after years of a calm mind. Relapses with other diseases can even be caused by patients’ actions — like the patient who continues eating too many hamburgers despite heart disease, or the person who takes her insulin improperly and has her diabetes flare up. Yet health care providers wouldn’t let patients suffer just because they messed up.

“We don’t say, ‘Okay. You didn’t take your insulin right, so I’m not going to prescribe it anymore. I’m going to let you die right here,’” D’Onofrio said.

To address these misconceptions, ER leaders emphasize the successes. “Once we have a patient that works well, I will go back to the nurses and say, ‘Hey, it was really great that so-and-so came in and we got them in treatment, and they are still in treatment,’” Moulin said. That makes doctors and nurses “feel like they made a difference,” Moulin added.

Sometimes, convincing staff that treatment works is as simple as getting them to do some treatment on their own. Sampson, of the Marshall Medical Center, told me about a patient who came in miserable, in withdrawal from opioids. Within 30 minutes of administering buprenorphine, the patient was visibly better — looking, in Sampson’s words, “human.” He got signed up into treatment after that.

At the end of it all, the nurse working with Sampson at the time, once a skeptic of buprenorphine treatment, told her, “We saved that person’s life. That was remarkable.”

Policymakers could do more to support addiction treatment

If there was a universal complaint among the people I talked to, it’s that different levels of government aren’t doing enough to support ER-based addiction treatment. In some cases, governments are even standing in the way.

Within emergency rooms, a consistent concern is all the regulations around prescribing buprenorphine. There is a special rule that allows providers in the ER to administer — but not prescribe — buprenorphine for up to 72 hours, particularly to treat withdrawal. But if a patient requires a longer-term prescription to tide them over before a follow-up appointment, providers have to be able to prescribe buprenorphine — and overcome all the hurdles that proper certification requires.

The providers I spoke to acknowledged that some regulations around buprenorphine are needed, since it’s an opioid that can be diverted for misuse. But the training requirements add an extra hurdle — one that doesn’t exist for medications for other medical conditions — that can prevent providers from treating addiction. And the strict regulations may even be self-defeating, since research suggests that the biggest reason people turn to illicit means of obtaining buprenorphine is a lack of legal access to it for addiction treatment.

The broader problem, though, is the lack of government support for addiction treatment in general. Over the past few years, the federal government has approved new funding here and there in response to the opioid epidemic that is going to addiction treatment. Some of that money has benefited the California ER program.

But the funding falls far short of the tens of billions that experts estimate is necessary to fully confront the opioid crisis. Not only that, but the new funding programs are typically limited grants, which will expire in a few years and only fund programs on the ground for one or two years at a time.

Imagine how this works for the ER program: You may not get enough funding to do the whole program to begin with, particularly to support not just the ER side of things but also the providers and clinics that will do follow-up appointments. Then, the funding will be limited to one or two years. So you’re starting this program that will presumably involve some costs for years to come, but the limited funding is only guaranteed for one or two years.

This is why experts have consistently told me that funding levels not only need to be much higher, but sustained over the long term, too. Wakeman, Flynn, and others invoked the Ryan White Care Act, passed in response to the HIV/AIDS epidemic, as a model; that law set up a permanent federal program that directs funding to ensure just about everyone can access HIV/AIDS treatment. There are also changes with health insurance programs, such as those Virginia took with Medicaid, that could ensure insurers not only pay for addiction treatment, but do so at rates that actually cover the costs of treatment.

Only once such steps are taken can the massive coverage gaps found in federal reports, from the surgeon general’s to the White House opioid commission’s, start to really close.

This extends to other kinds of addiction and other types of addiction treatment, beyond medication, too. In my time at the ER in UC Davis, I saw multiple cases that involved drugs besides opioids — particularly alcohol, which is linked to more deaths each year in the US than all drug overdoses combined. Better care is needed in these other areas as well.

“We’re working hard to not create a one-drug system of care,” Kelly Pfeifer, director of the High-Value Care Team at the nonprofit California Health Care Foundation, told me. “We’re trying to use the money and attention to the opioid epidemic to support our efforts to build a robust addiction treatment structure that is integrated with our health care system so that any person with addiction can get the care they need.”

That, at least, is the hope, even if it’s far from what the US does today.

“Everything we’re talking about is what we do for every other health condition,” Wakeman said. “This is really just bringing addiction treatment into the medical mainstream.”

The good news is that if this work is done, we may start to see fewer stories about all the overdose deaths each year and instead see more stories like Michael Curci’s.

Back at El Dorado County Community Health Centers, Curci reiterated how grateful he was for California’s ER program — the hope it gave him, after a life of feeling like he had little to look forward to. He reflected on reconnecting with family and friends, working, getting his own place and car, and the possibility of going to college.

“I know I’m going to get this right,” Curci said. “Because I’m going to do everything in my power to get this right. I do not want to be that person again.”

Do you ever struggle to figure out where to donate that will make the biggest impact? Or which kind of charities to support? Over 5 days, in 5 emails, we’ll walk you through research and frameworks that will help you decide how much and where to give, and other ways to do good. Sign up for Future Perfect’s new pop-up newsletter.

Sourse: vox.com