Jared Kushner may soon get his first big legislative breakthrough — with a prison reform bill.

The efforts of President Donald Trump’s son-in-law earned an endorsement last week from the president himself, who said at a White House summit on prison reform that if lawmakers get a bill to his desk, “I will sign it.” On Tuesday, Kushner’s favored bill, the First Step Act, was passed by the House of Representatives.

The bill would not reform or reduce how long people are sentenced to prison for, which has been the prime target of criminal justice reformers over the past few years. Instead, the bill focuses on rehabilitating people once they’re already in prison by incentivizing them, with the possibility of earlier release, to partake in rehabilitation programs. As Kushner explained at the White House summit, “The single biggest thing we want to do is really define what the purpose of a prison is. Is the purpose to punish, is the purpose to warehouse, or is the purpose to rehabilitate?”

But the second major step for the bill is the Senate, where it’s likely to face much stiffer opposition. The Senate opposition is all over the place — some prominent Democrats and Republicans argue that the bill doesn’t go far enough, while a Republican who blocked previous criminal justice reform efforts, Arkansas Sen. Tom Cotton, appears to be working in secret to build opposition to the First Step Act because it goes too far.

Even if it does pass, though, the bill wouldn’t amount to a very big change in America’s criminal justice system. That’s in part because the federal prison system makes up a relatively small portion of the US’s incarcerated population. Beyond that, the bill pursues some fairly mild reforms; after all, it couldn’t have gotten approval from Trump, who’s described himself as “tough on crime,” if it did a lot to reduce America’s prison population.

Still, if it passes, the First Step Act would be the first major federal criminal justice reform in years.

What the First Step Act does

The First Step Act, short for Formerly Incarcerated Reenter Society Transformed Safely Transitioning Every Person Act (Congress will do anything for a good acronym), is a fairly mild criminal justice reform bill. The bill’s limited reach is even written into its name, meant to indicate that the bill is only the first step in reforming the federal criminal justice system.

To understand why, it’s important to first understand the two main kinds of prison reform: the “front end” and “back end.” Front-end reforms are what people typically describe as sentencing reform: They focus on reducing the amount of time people spend in prison on the front end — meaning, when people are actually sentenced to prison. Back-end reforms, meanwhile, focus on cutting prison time once people are already incarcerated — by, for instance, offering credits for good behavior that may let someone get out earlier than they were sentenced for.

The First Step Act focuses exclusively on the back end. In doing this, the bill doesn’t help address the core cause of mass incarceration — that prison sentences are simply too long. But, advocates argue, it will still work to reduce the federal prison population.

The bill would do this in several key ways:

- The bill encourages inmates to participate in more vocational and rehabilitative programs, by letting them get “earned time credits” that allow them to be released early to halfway houses or home confinement. Not only could this mitigate prison overcrowding, but the hope is that the education programs will reduce the likelihood that an inmate will commit another crime once released and, as a result, reduce both crime and incarceration in the long term. (There’s research showing that education programs do reduce recidivism.)

- The bill increases the amount of “good time credits” that inmates can earn. Inmates who avoid a disciplinary record can currently get credits of up to 47 days per year incarcerated. The bill increases the cap to 54, allowing well-behaved inmates to cut their prison sentence by an additional week for each year they’re incarcerated. The change applies retroactively, which could essentially allow some prisoners to be released the day the bill goes into effect.

- Since the vocational and rehabilitative programs that already exist in federal prisons have a huge waitlist, the bill would authorize more funding — $50 million a year over five years — to support more programs. It also directs cost savings toward reentry and anti-recidivism programs. (Although any allocation of funds will need to be approved through Congress’s formal appropriations process in the future.)

Not every inmate benefits from all the changes. The system would use an algorithm to initially determine who can cash in earned time credits, with inmates deemed higher risk excluded from cashing in although not from earning the credits (which they could then cash in if their risk level is reduced).

But algorithms can perpetuate racial and class discrimination; for instance, an algorithm that excludes someone from earning credits due to previous criminal history may overlook that black and poor people are more likely to be incarcerated for crimes even when they’re not more likely to actually commit those crimes.

In a letter to lawmakers, the advocacy group Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, which typically backs criminal justice reform, wrote that the algorithm risks “embedding deep racial and class bias into decisions that heavily impact the lives and futures of federal prisoners and their families.”

The bill does put checks on and offers ways around the algorithm, but critics of the bill worry that those would not do enough.

The bill also excludes certain inmates from earning credits entirely, including undocumented immigrants and people who are convicted of high-level offenses. The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights criticized this too, arguing that “excluding entire groups of people from receiving early-release credits will undermine efforts to reduce prison overcrowding and improve public safety since such exclusions weaken the incentive to participate in recidivism-reduction programming.”

There are other complaints about the bill’s provisions, including claims that the funding it authorizes simply isn’t enough to overcome the giant waitlists for rehabilitation programs and concerns that it may facilitate more privatization of prison services.

The bill also makes other changes aimed at improving conditions in prisons, including banning the shackling of women during childbirth and requiring that inmates are placed closer to their families. These portions face very little opposition from just about anyone.

What the bill won’t do, though, is reduce or limit mandatory minimum sentences for drugs or other offenses. That’s in large part because the Trump administration, particularly Attorney General Jeff Sessions, really oppose anything that actually reduces prison sentences.

As a senator, Sessions blocked a previous criminal justice reform bill in large part because it would have effectively reduced prison sentences for some low-level offenses. As attorney general, Sessions characterized a bill that would reform mandatory minimums as “a grave error” — effectively killing the legislation.

By avoiding the front end reforms, then, the First Step Act tries to avoid opposition from the Trump administration and Sessions in particular. But in doing so, it’s drawn criticism from politicians and activists who are normally on the side of criminal justice reform.

The bill has led to some pretty bizarre battle lines in Congress

In the Senate, Democrats Cory Booker (NJ), Dick Durbin (IL), and Kamala Harris (CA) are normally on the side of criminal justice reform. But when it comes to the First Step Act, they have strongly opposed the bill — sending a letter on Thursday condemning the legislation as “a step backwards” and urging their Democratic colleagues to vote against it.

The prominent Democrats have been joined by several civil rights groups that typically back criminal justice reform, including the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Right and the American Civil Liberties Union. These groups sent out another letter this week, similarly asking House members to vote against the bill.

Other criminal justice reform groups, such as #Cut50 and Right on Crime, support the bill.

So what’s going on here? As noted above, the politicians and activist groups have some complaints about certain provisions in the bill (which you can read more about in their letters). But the primary concern isn’t really what’s in the bill; it’s what’s not in the legislation.

The letter from Booker, Durbin, and Harris makes this very clear — explicitly noting that they would have tolerated some of their concerns with the First Step Act’s provisions if such provisions came with broader criminal justice reform.

“We have supported prison reform legislation with some of the deficiencies outlined above as part of broader criminal justice reform legislation that includes critical reforms to federal sentencing laws,” the Democrats wrote. “We have done so only because it was necessary to secure sufficient support for sentencing reform in a Republican-controlled Congress. However, we are unwilling to support flawed prison reform legislation that does not include sentencing reform.”

Part of the reasoning here is that prison reform on its own is too little. Without cutting how many and how long people are going into prison, you can never hope to fully address mass incarceration and prison overcrowding.

But the opposition is also partly strategic. Without the more widely accepted prison reform provisions, a criminal justice bill with sentencing reforms is simply much less likely to pass Congress. So passing this bill now could pose a threat, the thinking goes, to future criminal justice reform efforts.

Rep. Hakeem Jeffries (D-NY), who introduced the First Step Act in the House with Rep. Doug Collins (R-GA), shot back at the criticisms in his own letter to his colleagues. He claimed that the Booker-Durbin-Harris letter is “riddled with factual inaccuracies and deliberately attempts to undermine the nationwide prison reform effort.”

Jeffries argued that the bill’s critics aren’t properly considering the political realities of the current situation, with a Republican in the White House and Republican control of Congress. “For this reason, it is not clear how exactly the opposition proposes to achieve comprehensive criminal justice reform without first considering the bipartisan prison reform legislation pending in the House,” he wrote.

From this view, it’s better to pass something that makes a bit of progress than nothing at all.

Still, the Democratic opposition means the First Step Act faces tough odds in the Senate, where it will likely need 60 votes, including at least nine Democratic votes, to pass. Senate Judiciary Chair Chuck Grassley (R-IA), who oversees criminal justice issues in the chamber, also reportedly opposes the bill because it doesn’t include sentencing reform — leading Politico to label it as “DOA in the Senate.”

While all this is going on, at least one major opponent of criminal justice reform appears to be trying to stop the First Step Act in the Senate by other means. Although Sen. Cotton hasn’t taken a public position on the bill, emails obtained by Politico suggest that his office has been reaching out to law enforcement agencies to get them to oppose the bill. One organization, the Federal Law Enforcement Officers Association, appeared to drop its support of the bill following Cotton’s request.

Cotton, for his part, has argued that the US actually has an “under-incarceration problem.” From his perspective, stiffer prison penalties deter crime, keeping Americans safe.

This goes against the empirical evidence on the topic, which has consistently found that more incarceration and longer prison sentences do little to combat crime. A 2015 review of the research by the Brennan Center for Justice estimated that more incarceration — and its abilities to incapacitate or deter criminals — explained about zero to 7 percent of the crime drop since the 1990s, though other researchers estimate it drove 10 to 25 percent of the crime drop since the ’90s.

And other studies have shown that more incarceration can even lead to more crime. As the National Institute of Justice concluded in 2016, “Research has found evidence that prison can exacerbate, not reduce, recidivism. Prisons themselves may be schools for learning to commit crimes.”

The First Step Act starts to chip away at this problem at the federal level, although its overall impact is unlikely to be very large.

Even if the bill passes, its effect on mass incarceration will be relatively small

The bill still faces a tough road ahead through the Senate. But assuming it passes, even its most ardent supporters acknowledge that it will have a fairly small impact on the size of the federal prison system — contributing only bit by bit to reductions in incarceration over time if inmates take up rehabilitation programs, behave well, and therefore earn more credits to get out of prison early. In a broader national context, this means the bill will have a very little effect on mass incarceration overall.

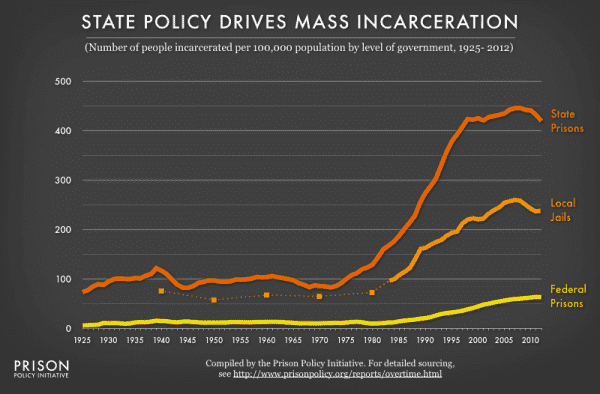

That’s because the federal prison system, which is what this bill focuses entirely on, is only a small part of the overall US prison system.

Consider the numbers: According to the US Bureau of Justice Statistics, 87 percent of US prison inmates are held in state facilities (and most state inmates are in for violent, not drug, crimes). That doesn’t even account for local jails, where hundreds of thousands of people are held on a typical day in America. Just look at this chart from the Prison Policy Initiative, which shows both local jails and state prisons far outpacing the number of people incarcerated in federal prisons:

One way to think about this is what would happen if Trump used his pardon powers to their maximum potential — meaning he pardoned every single person in federal prison right now. That would push down America’s overall incarcerated population from about 2.1 million to about 1.9 million.

That would be a hefty reduction. But it also wouldn’t undo mass incarceration, as the US would still lead all but one country in incarceration: With an incarceration rate of around 593 per 100,000 people, only the small nation of El Salvador would come out ahead — and America would still dwarf the incarceration rates of other developed nations like Canada (114 per 100,000), Germany (78 per 100,000), and Japan (45 per 100,000).

Similarly, almost all police work is done at the local and state level. There are about 18,000 law enforcement agencies in America, only a dozen or so of which are federal agencies.

While the federal government can incentivize states to adopt specific criminal justice policies, studies show that previous efforts, such as the 1994 federal crime law, had little to no impact. By and large, it seems local municipalities and states will only embrace federal incentives on criminal justice issues if they actually want to adopt the policies being encouraged.

Criminal justice reform, then, is going to fall largely to municipalities and states, and a bill that might slightly cut incarceration on the federal level isn’t going to have a very big effect. (To this end, many cities and states are actually way ahead of the federal government when it comes to criminal justice reform, with many passing the kinds of sentencing reforms that the federal system has struggled to enact.)

That’s not to downplay the work of criminal justice reformers who are trying to reduce the size and burden of what amounts to a fairly large prison system at the federal level. But to understand the bill, it’s important to put its full impact on mass incarceration in the broader national context.

Sourse: vox.com