Finding the best ways to do good. Made possible by The Rockefeller Foundation.

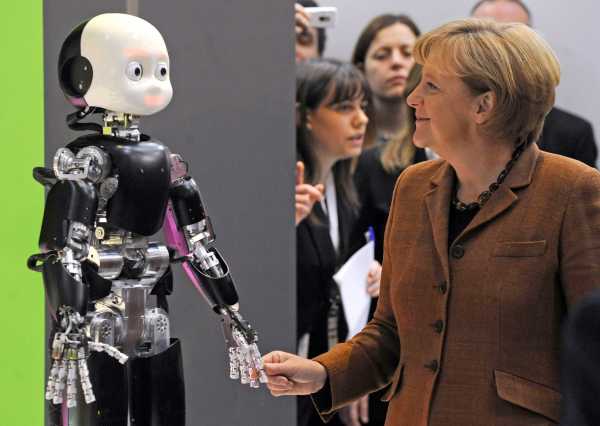

One in four Europeans want artificial intelligence — not politicians — to be making important decisions about how their country is run. In the UK and Germany, the proportion is even higher: one in three. In the Netherlands, fully 43 percent want AI to decide policy.

These striking findings come from a new survey conducted by the Center for the Governance of Change at IE University in Spain, which polled people in eight European countries. The questions explored how citizens feel about the way technology is transforming the world, from the workplace (40 percent think their company will disappear in a decade if it doesn’t make big changes) to the public square (68 percent fear that people will socialize more digitally than in person).

But the finding that 25 percent of Europeans want AI to replace politicians is the most striking — and worrying. That’s millions of people clamoring for a high-stakes change that would have been unthinkable a decade ago.

I understand the respondents’ impulse. Many Europeans are frustrated with their politicians, and for good reason. The impossibly complicated and drawn-out Brexit saga alone feels like reason enough to give up on human policymakers.

Faced with the foibles and failures of politicians, it can be tempting to outsource big policy decisions to machines, which might seem like they can make choices more objectively.

The problem is AI is not as objective as you might think. For one thing, human bias can creep into automated decision-making systems. If the initial data used to train them is problematic, the recommendations they churn out will be problematic, too. For instance, we’ve seen example after example after example of how algorithmic bias can affect facial recognition technology, and researchers warn it could also affect other technologies. There’s reason to suspect this bias problem would show up when AI is deployed in the arena of political decision-making.

Even putting aside the problem of bias, computer models often fail to capture the many factors at work in a human society and how they interact, because societies are incredibly complex behavioral systems. Even if a model accurately identifies all the most important factors in a given situation, that might not map onto a different time and place. As Neil Johnson, a physicist who models terrorism, put it to me last year, a model is “a cartoon of the real world.”

Johnson and I were talking about a specific model that’s being developed in Norway in order to evaluate competing policy options and help the government pick the most effective one. The Modeling Religion in Norway project looks at different policies the government could implement to integrate Syrian refugees, and aims to predict what will happen if one is chosen over another. As I explained in the Atlantic:

It’s an exciting idea that does hold some promise, but as Johnson pointed out, this kind of model should be viewed as offering an opinion rather than a surefire prediction. “It’s great to have as a tool,” he said, but we shouldn’t grant it sole decision-making power.

The quarter of Europeans who want AI to make policy decisions instead of politicians would do well to bear this in mind. AI can be a source of useful insights, but especially in a realm as complex and high-stakes as politics, we need human beings — like policy analysts and politicians — to interpret the insights from AI and determine the scope of their applicability.

Ironically, the same survey that showed many people want AI to drive policy also showed that a majority of Europeans fear robots may replace humans in most professions, and more than 70 percent believe that governments should implement firm policies to limit automation in businesses. This wasn’t lost on the Center for the Governance of Change, which called it “a strange paradox” in a statement.

Diego Rubio, the center’s executive director, said in the statement that Europeans’ desire to empower AI speaks to their disillusionment. “This mindset, which probably relates to the growing mistrust citizens feel towards governments and politicians, constitutes a significant questioning of the European model of representative democracy, since it challenges the very notion of popular sovereignty,” he said.

It’s entirely understandable to be fed up with the current political system. Let’s just make sure we don’t replace it with an AI system that’s just as flawed. That could actually make things worse because AI — and, by extension, its policy decisions — comes with the deceptive veneer of objectivity.

Sign up for the Future Perfect newsletter. Twice a week, you’ll get a roundup of ideas and solutions for tackling our biggest challenges: improving public health, decreasing human and animal suffering, easing catastrophic risks, and — to put it simply — getting better at doing good.

Sourse: vox.com