“This is what I would hope for – that players who aren’t gay come out strongly against homophobia.”

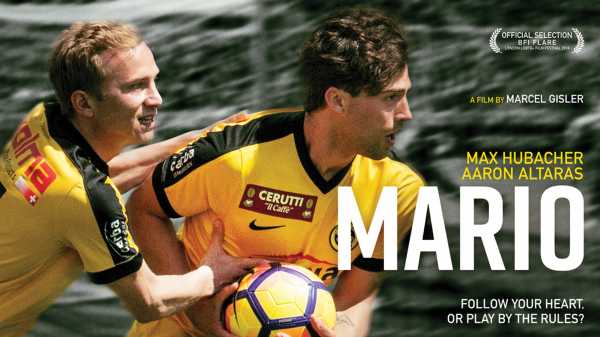

Aaron Altaras wants to see more support for someone like Leon Saldo, the character he plays in the new movie ‘Mario’, which opens in the UK on Friday. He’s sitting across from the film’s director and co-writer, Marcel Gisler, discussing football, forbidden love and their dual hopes of catching the attention of fans – and players – around the world.

“This film was made for all those who love the game,” says Gisler, “and it’s also hugely important to reach an audience that’s not LGBT. It’s just really difficult to reach them.”

However, Gisler and Altaras have cause for optimism with the timing of the release into British cinemas of ‘Mario’, which follows the story of two rising stars in the Under-21 set-up at the Swiss club Young Boys Bern.

Leon is initially the outsider and a challenger to Mario Luthi (played by Max Hubacher, who won Switzerland’s top acting award for his performance). Immediate tension brews between them; both players are talented, driven and prepared to fight for their spot on the first team.

But when the pair are moved into an apartment with one another, they develop a firm friendship which unexpectedly turns into something deeper. As their relationship intensifies, Mario and Leon become inseparable, yet Mario is desperate to hide their love from his team-mates. As rumours begin to circulate, the boys are forced to make a choice – their careers, or each other.

1:41 Watch the trailer for the award-winning 'Mario', which opens in selected UK cinemas on Friday

With England’s World Cup adventure reigniting the nation’s love affair with the beautiful game, and raised awareness around the repressive regime of host country Russia in terms of LGBT+ rights, there could hardly be a better week in the calendar for such a movie to find an audience. It’s the first full-length feature film to go behind the door of the dressing room at a professional club and show the difficulty gay footballers might face.

It’s topical too because late last month, Collin Martin became the seventh male pro footballer in history to come out publicly as being gay or bisexual. Of those seven, the 23-year-old Minnesota United midfielder joins Justin Fashanu and Anton Hysen in being the only players to have spoken of their sexuality while still being active in the sport (although Fashanu was actually between clubs at the time of his tabloid ‘coming out’ interview in October 1990).

Martin is following in the footsteps of Robbie Rogers, who had retired from football shortly before he came out, only to put his boots back on to play for Los Angeles Galaxy. The welcoming response Rogers received from both his Galaxy team-mates (with whom he became an MLS champion for the second time in his career in 2014) and the wider football world helped convince Martin that he didn’t need to hide that part of himself either.

“It’s still an amazing story, though. In Germany, Jogi Low once said that he wouldn’t recommend young players who were gay to come out, because they’d be crushed by the media. He felt it would be such a sensation, and that it would only work if a group who were gay or bi came out together.

“But I do think it’s going to happen soon, maybe in the Bundesliga or the Premier League. Perhaps if the anti-homophobia campaign was on the same scale as the anti-racism campaign… why don’t we have that? It needs big-name players, who have a standing in society. Whatever they said would have an impact.”

Altaras believes watching ‘Mario’ would give those stars the empathy to get involved in such a campaign. Gisler began work on the screenplay for the film back in 2010, taking the plunge into a subject he knew little about – “I’m not a big football connoisseur”. Swiss by birth, he has lived in Berlin since the early 80s, winning various festival prizes for his previous films and documentaries. He admits he was initially unsure if the subject matter of this movie was a good fit for him. “I had to be persuaded because it’s completely different to my other work. My last feature was more autobiographical, about a mother who doesn’t want to go into a home for old people. So this was a big challenge.

“But I was interested in the contradiction – a film about homosexuality in a workplace where it seems impossible to be gay, even now. There are inner conflicts there for your characters.

“Initially, my co-writer and I had different ideas on how to tell the story. He wanted something more like ‘Brokeback Mountain’, where the two guys have wives and children and their love story is a secret from everyone. I thought that was a little bit old-fashioned; I wanted to put a more modern, younger focus on the story.”

“Nowadays, no public figure in a world like professional football is a vocal homophobe because it’s not politically correct to be. The problems are not so much personal – it’s more systemic or industrial.”

He was also wary of how quickly society and sports are moving with regards to LGBT inclusion and visibility.

“When we finished the first draft of the screenplay, I always thought that by the time the film was released, we might look a little late with it as several players might have come out by then. So the fact that gay or bi players still don’t feel able to be out openly… well, it’s a bad surprise.”

Gisler concentrated his efforts on creating an authentic world and quickly won the trust and co-operation of officials at Young Boys Bern, one of the Swiss Super League’s biggest clubs (they won the domestic title last season, for the first time in 32 years).

Filming locations include their Stade de Suisse stadium and training ground, while the match action shows Mario and Leon convincingly forming an effective strike duo for the ‘Nachwuchs’ U21 team. Eventually, Mario and his agent Peter (Andreas Matti) are called into a meeting when the rumours of the forward’s relationship with Leon reach the boardroom; the ultimatum given is tough to take for the player, and might have reflected badly on Young Boys.

“They read the screenplay, and had no comments – so we did the film!” says the director. “I thought maybe they didn’t quite read exactly what it was about, and that when we showed them the finished film, they would maybe have a problem. But there was no problem. I talked with one of the directors on the board; he thought it was a realistic reaction. So there was no censorship at all from the club, and that was really great.”

Altaras says he and Hubacher were made welcome by everyone at Young Boys; it’s hard to think of a Premier League club permitting such access to a film crew and cast. “They got VIP tickets for me and Max, sitting next to the injured players who all knew who we were. They treated us very well.

“They were proud of the project, proud that they were the club doing it, and that’s just amazing. Because who else would do that? There’s a lot of anti-homophobia campaigns going on at different clubs, but this was on a different level. They gave us players as extras and the club name, everything they have… and we had complete creative control. The club doesn’t look too good in parts, but they accepted it all.”

The actor, 22, sees the film’s release in European territories in the coming months as a great opportunity for football clubs to show they are serious about tackling homophobia. “It deserves to be shown in stadiums, and in the youth teams, because that’s exactly how you would solve the problem.

“You need to give people an image of what it shouldn’t be like for players like Mario and Leon. You could then raise a different generation of football players. We all know that, in these youth teams, they live there all day, they get their education there, so it’s not impossible to do it.”

The drama peels back the layers of a complex football dressing-room environment – the competition between individual players, the hypermasculinity, and the casual sexism lingering under the surface, which allows homophobia to fester from a lack of awareness. At one point, Mario asks his best friend Jenny (Jessy Moravec) to pretend to be his girlfriend so he can fit in with the group once again and get his career back on track.

“All these guys together doing this sport, and this virility – it’s a lot of testosterone,” says Gisler. “It’s hard to explain… maybe in the military, it’s the same thing. When a lot of men come together, there is always a certain intention to prove their virility, and to put on a front.

“The weakness of the others is always used to strengthen their own position. There is a hierarchy in teams, especially the last year in the U21s before the decision comes as to whether you become a professional or not. Only one or two will go on, so the competition is harder.”

Altaras agrees, adding that competition often manifests itself in discussions around sex, from which closeted gay and bi players would feel excluded or put under pressure to conform. “There’s an underlying truth that the mistreatment and the lack of respect for women is often the root of homophobia. When you grow up in such a male-dominated world, you know where it’s coming from.”

So what would a real-life Mario, a closeted professional footballer, think about the movie? Gisler doubts such a player would get to see it. “Sadly, I think they’d be too afraid to go – even a young player,” he says. “I remember what Corny Littmann told me. He was the former president of St Pauli, an openly gay man working in football.

“He said if you want to know which player is gay, you have to look at which one has collected the most red cards. Because it’s the guys who press so much on the pitch, to prove that they are real men. Then nobody would have the idea they could be gay. Maybe he was being a little bit sarcastic, but there is some truth in it.”

The film certainly doesn’t flinch on the football – the tackles are full-blooded, there’s energy and enthusiasm from Hubacher, Altaras and their on-screen team-mates, and it’s all set in a fully realised, authentic club atmosphere, both on the pitch and off it. Through it all, Mario and Leon are determined to remain professional, but ultimately it’s a challenge that puts their love under enormous pressure.

Altaras says it is the old stereotypes that should break, and not the spirit of the players affected. “I want people to take away that you can be really tender as a person, but you can still be a good sportsman. It’s not mutually exclusive. You can be tough and soft at the same time.

“Mario and Leon are both like that – they are tender and loving with each other at home, and then amazingly aggressive footballers.”

Strong characters, playing with conviction… there’s a lot for fans to learn from ‘Mario’ and it’s sure to spark a few conversations for audiences on the way out of cinemas. Altaras says it’s perfect for a football club to screen to their squads too – “we’ve done it all for them, it’s a finished project!”

As Collin Martin said late last week, in an interview with The Athletic, the reaction to gay footballers shouldn’t be something to fear. Asked for his advice to any players in the closet, he replied: “Give your team-mates a chance… These are your friends, these are the people that you love and care about, so just be honest with them.

“I think you’ll find that there’s going to be no problem with your sexuality and how you go about life – because they’ll appreciate you for the person that you are.”

A few more players stating that they would be supportive, perhaps after seeing ‘Mario’, might just be an additional cause for celebration for English football this summer.

‘Mario’ is released in selected UK cinemas by Peccadillo Pictures on Friday.

Also See:

Sourse: skysports.com