Michael Moynihan

Nothing beats being there, according to the old advertising slogan, and at Gaelic games, attendance is often its own reward.

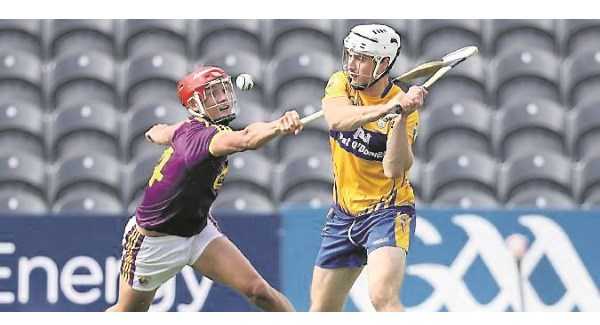

There were plenty of empty seats at the weekend’s All-Ireland hurling quarter-finals

Last Sunday in Thurles, after the minor game between Galway and Kilkenny, one of the Galway defenders found his family sitting in the stand and clacked his way up the steps to them, where he was hugged by one and all. One small boy in maroon, a brother or nephew perhaps, grabbed him tight and was embraced in return, while the slaps on the back from the adults spoke volumes.

It was a moving sketch of what the GAA means to people, but there were only 18,596 in the stadium to witness it.

Thurles wasn’t the only place with the ribs of the stadium showing last weekend. There were 10,255 people in Páirc Uí Chaoimh for Wexford versus Clare last Saturday, and the low attendances weren’t confined to hurling; just over 30,000 were in Croke Park for Sunday’s double-header of Super 8 games, Kildare-Monaghan and Galway-Kerry.

There were 53,500 people in Croke Park on Saturday evening for the Dublin-Donegal and Tyrone-Roscommon double-header, but that still represents a fair drop from last year’s quarter-finals. One of those quarter-final double-headers (Armagh-Tyrone and Dublin-Monaghan), for instance, filled Croke Park, and was thus, at 82,000, almost as well-attended as the four Super 8 games last weekend.

Is this a temporary blip or the start of a long-term decline? Any economist would laugh at drawing conclusions from a sample size that small, but the GAA may need to take note of long-term trends in other sports and other jurisdictions.

In America, for instance, attendances are down in most of the big professional leagues, with the NBA — played in smaller venues than the large open-air stadia of baseball, American football, and soccer — the outlier which bucks the trend.

In an interesting piece for New York magazine, writer Will Leitch pointed out that whereas for decades every US sport based its revenue on getting people to pay into venues, that is no longer as big a driver in sports income there. Leitch referred to the profits being reaped by Major League Baseball from “expanded partnerships, local television ratings, and its own media-rights deals”, for instance, while the wildly profitable NFL attributed its improvement to a new “Thursday Night Football television package and increased media payments from other properties”.

The analogy with the GAA doesn’t quite stack up, of course. The NFL generates around $14 billion (€12bn) in overall revenues. The GAA remains heavily dependent on bums on seats for income. The focus on the organisation’s income from broadcasting rights for Gaelic football and hurling — significant but still dwarfed by attendance revenues — is an easy stick with which to beat the GAA, and one which can provoke a ‘here we go again’ reaction, but it needs to be teased out.

Why? Because it affects attendance revenues, which in turn affect broadcast deals.

Last week in these pages former Wexford All-Ireland winner Tom Dempsey expressed his concerns about attendance for the Wexford-Clare game in Páirc Uí Chaoimh:

There were plenty of other contributions along those lines: football columnist John Divilly expressed his surprise here yesterday at the lack of atmosphere in Croke Park for Kerry-Galway, where he could hear Kerry forward Paul Geaney’s instructions to teammates from where he was sitting in the stands.

The significance of these low attendances is that in the GAA’s financial ecosystem — and like every other financial ecosystem, the word ‘delicate’ is taken as understood — everything is connected. The crowds create the atmosphere and the sense of occasion, and those are strong selling points of the GAA in discussions with broadcasters.

If that atmosphere is lacking or sense of occasion underwhelming, that has an adverse effect on negotiations between the two, obviously enough.

Another complicating factor is one of the most basic influences on attendances: the identity of the teams taking part. The departure of Mayo from the football championship, for instance, deprives the latter stages of the competition of a significant cohort of followers as well as a well-known quest narrative, both of which generate interest and revenue.

On the other hand, Croke Park will be happy with the arrival of Cork and Limerick in the hurling semi-final in a couple of weeks, as these (relatively) new sides traditionally bring big support to the capital.

This is the ‘known unknown’ of financial planning in the GAA, the way counties can drift to the front of the peloton and energise the championship for long or short periods.

The known known is the need to be more spectator-friendly in fixture locations. The GAA has proved willing in the past to tinker with rules that show up poorly when road-tested. Next year some more joined-up thinking will be needed to help attendances recover.

PaperTalk GAA Podcast: Dalo on a different Limerick, Divo on Galway’s plan and Kerry’s collapse

Sourse: breakingnews.ie