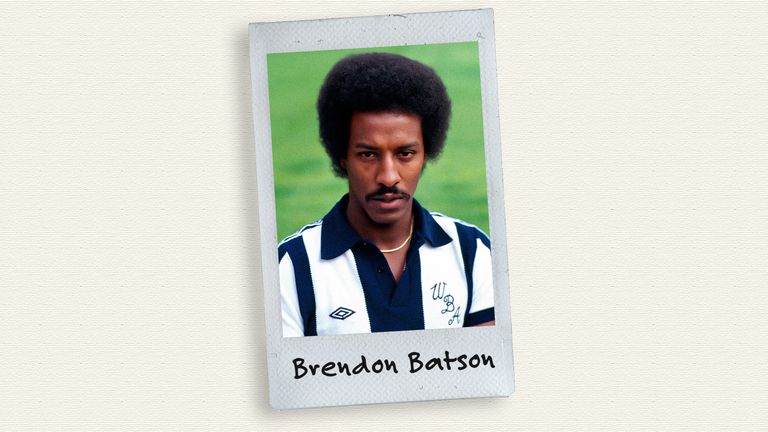

Following the release of his autobiography, The Third Degree, former West Brom defender Brendon Batson speaks exclusively to Sky Sports about Len Cantello’s controversial testimonial at the Hawthorns, the ‘Three Degrees’ and “breaking down barriers” in football

Image: Brendon Batson speaks exclusively to Sky Sports following the release of his book The Third Degree

Brendon Batson had never been in a dressing room like the one he found himself in before Len Cantello’s West Brom testimonial in 1979. He was surrounded only by Black players.

Remarkably, the game pitted an all-Black team against an all-white team.

“It couldn’t happen today,” Batson tells Sky Sports following the release of his autobiography The Third Degree. “There’s no need for it to happen now,” he adds. “I don’t think we had a conscious thought about it, but it was a way of breaking down barriers.”

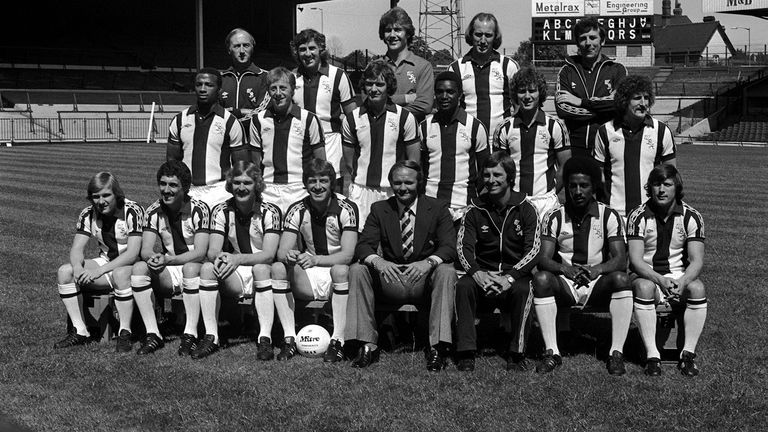

Image: The Cyrille Regis XI line up at the Hawthorns before Len Cantello's testimonial in 1979

Batson played for West Brom at the time, with Cyrille Regis and Laurie Cunningham. They were known as the Three Degrees. It was the first time three Black players were regulars in the same top-flight side in Britain.

Cantello’s testimonial, now known as the ‘Blacks vs Whites’ game, was a wholly different proposition though. Black players from up and down the country had come to the Hawthorns to represent their community. For once, being Black didn’t make them the odd one out.

“We all knew as individuals and collectively what our journey had been like to get to that dressing room,” says Batson. “We knew what we had to go through. We knew what our parents had to go through. And we knew what, in terms of the wider Black community, we knew what they were having to go through.”

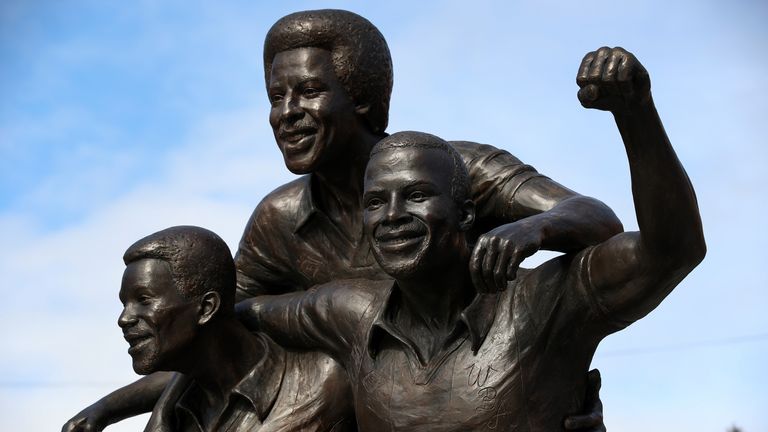

Image: A statue of Laurie Cunningham, Brendon Batson and Cyrille Regis stands outside the Hawthorns

Batson, a child of the Windrush generation, had never known football before arriving in the UK as a nine-year-old. From being told, ‘Maybe cricket is your game’, after his first trial to slipping over a banana thrown from the crowd on his West Brom debut, Batson was reminded at every turn that the game wasn’t for ‘people like him’.

His story, sadly, was not an exception. There was a shared lived experience in that dressing room, which is why this was more than a testimonial to the team captained by Regis.

“We as players said, ‘We are representing our community, so let’s make sure that we flipping win’,” Batson recalls. This was a chance to set the record straight. To quash the ill-conceived, bigoted notion that Black players were somehow less than their white counterparts simply because of the colour of their skin.

“There was a whispering campaign around Black players,” says Batson. “‘They’re lazy. They’re not brave. They don’t want the cold. They can’t tackle’. All that sort of rubbish.” These were the stereotypes Batson and his generation had to endure on their journey to becoming professionals and throughout their careers.

Image: Batson was part of an exciting West Brom team that finished third in the 1978/79 season after their title bid faltered in the second half of the campaign

It was, understandably, an environment that drove many away. “A lot of Black parents were saying to their boys, ‘No, you’re not going to take up that apprenticeship contract’,” says Batson. “There was almost a discouragement because we weren’t seeing any Black players within the Football League.”

Cantello’s testimonial certainly addressed the issue of visibility. “We could’ve fielded two teams,” Batson adds, “I didn’t realise there were so many Black players about to be honest.”

Football stadiums were almost exclusively white spaces at the time. Racism on the terraces was overt. The sheer volume of the abuse was striking, Batson says in his book. It could be heard on broadcasts, but was rarely called out.

Commentator Gerald Sinstadt was one of the first to do so when he referenced the booing West Brom’s Black players were subjected to at Old Trafford in December 1978. This act, though fleeting, would become defining in the legacy of one of sport’s most recognisable voices. Catch the moment from 0:20 in the video below.

YouTube Due to your consent preferences, you’re not able to view this. Open Privacy Options

The game was a thriller that West Brom won 5-3, but Batson’s overriding memory was this acknowledgement. “It was a big thing,” he says. “I don’t recall any commentators saying that. Gerald deserves a lot of plaudits for being brave enough to do it.”

Other than these rare moments of recognition, Batson was left to fend for himself. “My view was, ‘I’ll see you next week. I’ll see you next month. I’ll see you next year. This is my chosen profession. You’re not going to drive me away from the pitch’,” he says.

“That was the attitude for most of the Black players around at the time,” Batson adds. “That’s why I’ve got great admiration for those players around my era, despite everything else going on, despite the lack of support from the authorities, the Black players kept on coming forward in ever-increasing numbers.”

Cantello’s testimonial was a chance to showcase that. “It was going to be unique,” says Batson. “There were hardly any Black supporters at the time. We thought it would encourage more spectators to come into the ground and support.” The atmosphere around the Hawthorns that day was quite different to regular match days, Batson recalls.

Image: Brendon Batson continued to have an impact after his retirement in his role as PFA deputy chief executive

“There were a lot of Black supporters within the ground, but there was also a lot of excitement outside,” he says. “It was like a big party; I think people put stalls up and were cooking jerk chicken and rice and peas. We didn’t see a lot of that, but we knew it was going on.”

The 6,750 in attendance were treated to “an evening of first-rate entertainment”, according to the Birmingham Daily Post’s report. The Cyrille Regis XI were victorious, beating Cantello’s West Brom XI 3-2 after coming from behind with goals from Cunningham, Stoke’s Garth Crooks and Hereford United’s Stewart Phillips.

The report added: “Fears that the black versus white contest – the first ever at professional level – could be explosive were soon dispelled and the game took place in front of a crowd determined to enjoy the skills on view.”

As was so often the case, that generation of Black players were making history without knowing it. They helped to shape the English game into what we know it to be today. Speaking to Batson, a true footballing trailblazer, it becomes obvious how little space there was to acknowledge the defining role he played.

Image: Batson, pictured at Highbury playing against Arsenal, made 10 appearances for the Gunners before joining Cambridge

Batson was, after all, the first Black player to play for Arsenal. This is a fact he wasn’t aware of until the 1990s, years after his career had finished, when he was introduced at an anti-racism event at Stamford Bridge.

“I must have had a bit of a jolt because I thought, ‘I never knew that’,” he says. “It was a bit of a shock to me. It never occurred to me or had any real significance at the time.”

For Batson, the greatest achievement of his career was simply being recognised as a professional player. “I was very proud of that,” he says.

You can buy Brendon Batson’s autobiography, The Third Degree, here for £19.95.

Sourse: skysports.com