What is happiness?

It’s a very old question. And no one really knows the answer, although theories abound.

Aristotle was one of the first to offer what you might call a philosophy of happiness. For him, happiness consisted of being a good person, of living virtuously and not being a slave to one’s lowest impulses. Happiness was a goal, something at which humans constantly aim but never quite reach. Epicurus, another Greek philosopher who followed Aristotle, believed that happiness was found in the pursuit of simple pleasures.

The rise of Christianity in the West upended Greek notions of happiness. Hedonism and virtue-based morality fell somewhat out of favor, and suddenly the good life was all about sacrifice and the postponement of gratification. True happiness was now something to be attained in the afterlife, not on Earth.

The Enlightenment and the rise of market capitalism transformed Western culture yet again. Individualism became the dominant ethos, with self-fulfillment and personal authenticity the highest goods. Happiness became a fundamental right, something to which we’re entitled as human beings.

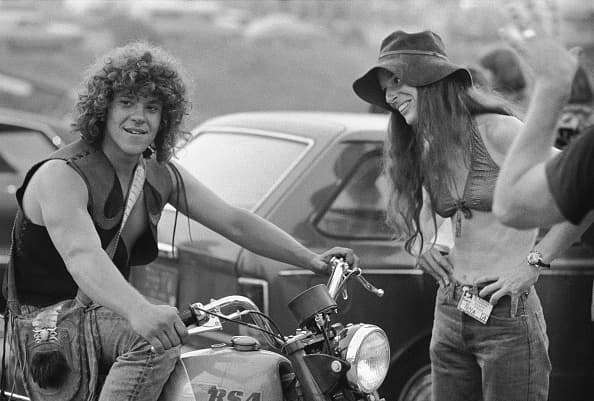

A new book entitled The Happiness Fantasy by Carl Cederström, a business professor at Stockholm University, traces our current conception of happiness to its roots in modern psychiatry and the so-called Beat generation of the ‘50s and ‘60s. He argues that the values of the countercultural movement — liberation, freedom, and authenticity — were co-opted by corporations and advertisers, who used them to perpetuate a culture of consumption and production. And that hyper-individualistic culture actually makes us much less happy than we could be.

I spoke to Cederström about how this happened and why he thinks happiness ought to be seen as a collective project that promotes deeper engagement with the world around us.

A lightly edited transcript of our conversation follows.

Sean Illing

The prevailing conception of happiness today is something like self-actualization, which is rooted in the “human potential movement” of the 1960s. The idea is that we’re happy if we reach our full potential as human beings and live authentically.

You call this our “happiness fantasy.” Why?

Carl Cederström

I think there have been happiness fantasies during all periods. My point is that it’s impossible to actually know what happiness is. But you can see happiness as reflecting the accepted values during a particular era, and those values evolve over time. So there’s always a strong connection between popular morality and how we think of happiness.

What’s interesting to me is that it’s not really until the Enlightenment era that we get this ideal of happiness as something that we, as human beings, can fully achieve in our lives. And it’s not really until the middle of the 20th century that this vision of happiness becomes the dominant cultural norm in Western society.

Sean Illing

How did that happen? What cultural forces conspired to cement this view of happiness?

Carl Cederström

Well, as with all histories, you can choose how far back you want to go, but I trace it back to the early psychoanalytic movement at the beginning of the 20th century. Although Sigmund Freud didn’t think human beings were especially designed for happiness, there were other figures who emerged from that movement, people like the Austrian psychoanalyst William Reich, who popularized this idea that happiness was connected to free love and free sexuality. These ideas got picked up by the early Bohemians of the 1940s in the US and later in the ‘60s and ‘70s countercultural movement.

Happiness became increasingly about personal liberation and pursuing an authentic life. So happiness is seen as a uniquely individualist pursuit — it’s all about inner freedom and inner development. This is still the foundation of how our culture tends to conceptualize happiness.

“This mania for individual satisfaction and this idea that buying and collecting more stuff will make us happy has produced a spectacularly unequal world”

Sean Illing

How did an anti-corporatist movement in the 1960s built on the idea of personal liberation and sexual freedom get co-opted by the very thing it was rejecting — consumer culture?

Carl Cederström

This is really what most of my book is about. By the end of the ‘60s, there’s a feeling that society is not allowing people to be authentic, that corporations are the enemy. People are thirsting for solidarity, and they see corporate life as dead and two-dimensional. And this is very powerful stuff that upends society.

But what happens as you move through the ‘70s and into the ‘80s is that the political conditions start to shift and corporations start to address all these concerns. You actually see articles in places like the Harvard Business Review about how to attract a “revolutionary spirit” and bring the youth into the corporate world.

Obviously, there’s a lot to say about how this happened, but the short version is that corporate America and the advertising industry changed their tactics and vocabulary and effectively co-opted these countercultural trends. At the same time, there were leaders like Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher who were advancing a very individualistic notion of happiness and consumerism, and all of this together had a huge impact on our culture and politics.

Sean Illing

You’ve hit on something that I think has to be unpacked. So I think Karl Marx got a lot of things wrong, but one of the things he got right was his idea that cultural values are a reflection of the prevailing economic order, and not the other way around. As you note in the book, our idea of happiness has been transformed to make us better consumers and producers, and that’s not an accident.

So is there any way for us to truly change our collective conception of happiness without also changing the underlying economic structure?

Carl Cederström

Wow, that’s a really good question. I think the honest answer is probably no, but it’s tricky. Part of what I want to say in this book is that the view of happiness we have now could not have come about if we didn’t have the kind of economic order we have.

The main point of the book is that the idea of happiness we now have, this pursuit of authenticity and personal freedom, may have once been a genuinely noble goal, but over time, these values have been co-opted and transformed and used to normalize a deeply unjust and undesirable situation.

There really is no way to accurately compare happiness today with happiness 50 or 100 years ago, but this mania for individual satisfaction and this idea that buying and collecting more stuff will make us happy has produced a spectacularly unequal world, and it has, in my opinion, left people less fulfilled and more empty inside.

Sean Illing

Do you think our hyper-individualist culture has set us up for disappointment? In other words, can we be genuinely happy if our primary aim is self-satisfaction?

Carl Cederström

I don’t think so. I think that ends where we are now, with a culture of extreme individualism and extreme competitiveness and extreme isolation. I think we do end up in a situation where people feel constantly anxious, alienated, and where bonds between people are being broken down, and any sense of solidarity is being crushed.

I think a meaningful sense of happiness would need to be a collective one. For a very long time, we’ve looked at ideas of collective happiness as ugly or creepy or totalitarian, but they need not be. I believe we desperately need to reimagine what collective happiness might look like in 2018.

“Capitalism has been very successful at presenting human life as an individual pursuit, but that’s a lie”

Sean Illing

I want to circle back to that potential reimagining, but first I think there’s an uncomfortable idea worth engaging. Capitalism is built on a set of assumptions about human nature: We’re self-interested, obsessed with status and prestige, and inherently competitive. If all of these assumptions were wrong, it’s highly unlikely that capitalism would work as well as it does.

What does all this suggest to you?

Carl Cederström

I think there’s a fundamental human desire to feel connected to other people. I also think capitalism has been very successful at presenting human life as an individual pursuit, but that’s a lie. Human life is far more complicated than that, and we’re all dependent on other people in ways we rarely appreciate.

You’re right, though. Like any political or economic ideology, capitalism appeals to something real about human nature. And the justification for capitalism has always been enjoyment and satisfaction — and that’s a powerful message. Human beings don’t have to be narcissistic and ultra-competitive, but if we’re thrown into a system that incentivizes these things, it’s obvious that we will be.

Sean Illing

Your book is focused on the Western world, but do you think the East, with its very different religious and cultural traditions, in general has a better view of happiness that the Western world?

Carl Cederström

No question about it, but I have to be honest and say I don’t understand enough about those traditions to speak in any detail about them. I will say this, though. I think Western culture has adopted some of these traditions and practices, like meditation, in order to be better at coping with our own situation. But maybe we’re missing the other, more important part, which is about letting go of yourself.

Sean Illing

That’s interesting, and seems right to me. I find that a lot of people borrow practices like meditation or yoga and then divorce them from their cultural or spiritual roots, and then they become just another tool of self-fulfillment.

Carl Cederström

I think that’s absolutely right.

Sean Illing

You said earlier that we need to reimagine a new happiness fantasy, one that is less self-involved and more grounded in the world around us. What does this conception of happiness look like, and how do we build it?

Carl Cederström

One thing I noticed while tracing this happiness fantasy over time was that I almost exclusively came across male voices. It was always men articulating the vision of happiness, and they were affirming values that were important to them and their sense of fulfillment and pleasure. I think that’s worth noting.

As for your question, I think a new happiness fantasy would, first of all, acknowledge that these values have been used to exploit people at work, and have been used to normalize a situation of precarity and austerity. And to imagine a new one, we would need a fundamentally different set of values. And I think that starts with a more collective consciousness.

Instead of obsessing over the self-actualized perfected person, maybe we should care more about equality, community, vulnerability, and empathy. Maybe we should get out of our heads and be more present in the world around us. I think that’s how we build a better world.

Sourse: vox.com