Keren Landman is a senior reporter covering public health, emerging infectious diseases, the health workforce, and health justice at Vox. Keren is trained as a physician, researcher, and epidemiologist and has served as a disease detective at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

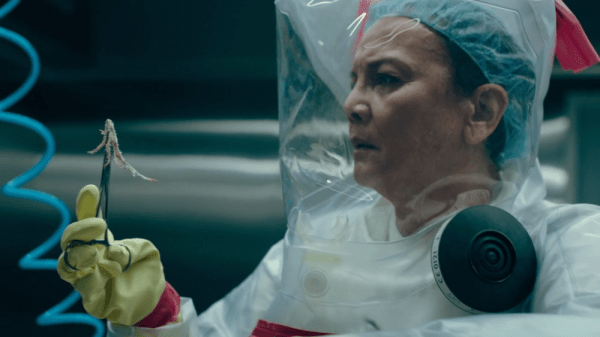

The second episode of the HBO hit The Last Of Us opens with a scene in Jakarta, Indonesia. It’s set in 2003, at the beginning of a (fictional) fungal pandemic that goes on to destroy the world as we know it. After an expert in fungal biology evaluates the body of an infected factory worker, she speaks quietly to a military official who has asked for her help controlling the pathogen’s spread.

“There is no vaccine,” she says to his stricken face.

It was true in real-world 2003, and it’s true now: Although vaccines against bacterial and viral diseases abound, no vaccines against any fungal pathogens are licensed for human use.

It’s not for lack of trying: Dennis Dixon, who leads bacterial and fungal research at the National Institutes of Health, said there’s been “continuous activity” aimed at developing fungal vaccines for decades. But a variety of challenges both scientific and economic have conscripted even more promising fungal vaccine candidates to the pharmacologic dustbin — to the detriment of human health.

The zombie-causing fungus in the show is mostly fictitious — at least, as a human pathogen. In reality, most severe fungal infections in humans affect immunocompromised people, including people with untreated HIV infection and those receiving cancer treatment, organ transplants, or medications for autoimmune diseases. (These usually manifest as lung and bloodstream infections or meningitis, and not zombification.)

However, some affect people with normal immune systems — ever had a yeast infection, or heard of valley fever? — and the global burden of fungal infections is expected to increase as the number of people receiving immunosuppressive drugs continues its upward climb and climate change accelerates.

The urgency of finding a vaccine to prevent any fungal infection — or ideally, preventing multiple types of fungal infections with one vaccine — is not new, but it’s growing.

Which raises the question: Why, in the year of our lord 2023, do we still not have any fungal vaccines? The answers highlight challenges in both the science and economics of vaccine development — and some idiosyncrasies about a kingdom of life already known for its very specific (and highly telegenic) weirdness.

A fungal vaccine would help prevent a lot of infections

Fungi are all around us: in the air we breathe, on the surfaces we touch, and all over the insides and the outsides of our bodies. Still, most of us are at low risk for fungal infections, as long as our immune systems are functioning normally.

The worst fungal infection likely to affect a person with a healthy immune system is probably one caused by a member of the Candida genus, which are technically yeasts (yes, yeasts are a type of fungus, as are mushrooms and molds). Vaginal yeast infections are an especially common form of candidal infection that often affects healthy people, leading to 1.4 million clinic visits a year in the US alone. Worldwide, an estimated 138 million women get four or more yeast infections a year. Other fungal infections common to healthy people include ringworm — which, surprise! isn’t caused by a worm at all — and infections of the nails on fingers or toes.

But fungal infections (including and beyond yeast infections) are a much bigger threat to people with compromised immune systems. Worldwide, fungi cause 13 million infections and 1.5 million deaths every year. And in 2018, treating these infections cost Americans nearly $7 billion.

Fungal infections are most common in immunosuppressed people. That complicates developing and deploying fungal vaccines.

The fact that the most severe fungal infections primarily affect immunosuppressed people creates some big challenges when it comes to developing vaccines to protect against them.

First of all, this makes it complicated to find participants for clinical trials testing fungal vaccines.

To determine whether a vaccine works, scientists need to test promising vaccine candidates — usually, prototypes that have successfully prevented the disease in experimentally infected animals —in large groups of humans. Because we live in a world with medical ethics, scientists can’t experimentally infect humans. Instead, they need to wait for people in the trial to naturally encounter the disease they’re trying to prevent.

The more rare that disease, the more people scientists need to follow (and for a longer time) to look for the disease. And while severe fungal infections are a growing problem, they’re still relatively uncommon.

Karen Norris, an immunologist at the University of Georgia’s veterinary school who leads a team developing a fungal vaccine candidate, said her team had “done the math” on the time it would take to study a hypothetical vaccine targeting a single fungal infection. “It’s doable, but it would take a couple of years to enroll that many patients,” she said.

It’s also hard to design vaccines that work for the immunocompromised people who need them the most. An effective vaccine works by training a person’s immune system to respond quickly to a certain germ — and suppressed immune systems are hard to safely train.

In some cases, it’s possible to predict immunosuppression — for example, when a person is preparing to receive chemotherapy or another immunosuppressive treatment. But not always: People with HIV and those who are born with immune system disorders can’t plan or predict the state of their immune systems.

That creates big challenges for scientists, who ideally want to develop vaccines that protect both people with healthy immune systems who go on to have immunosuppression, and those whose first diagnosis involves immunosuppression.

Another problem: Fungal cells have more similarities to human cells than do viruses or bacteria. That makes it more complicated to design a vaccine that trains the immune system to attack fungal cells without attacking our own cells.

The biggest barrier to fungal vaccines might be economic

Even if a vaccine is shown to be safe and effective in clinical trials, that doesn’t mean it will get to mass production and market: For that, it also needs to have the potential to make a profit. “The testing of a vaccine in this space is, to be honest, not that attractive to big pharma, etc., because they are not infections that occur at a high frequency in a lot of patients,” said Norris.

Even if a vaccine prevents a lot of illness and death in a group of people — and reduces the costs of their medical care — those benefits accrue to individuals and health care systems, not to the pharmaceutical companies who incur the costs of developing and producing the vaccine.

“It’s going to take someone to develop that tough market for this to go forward,” said Dixon. A viable vaccine will need to not only be effective at preventing disease, but effective at doing so in enough people to make producing the vaccine at scale a worthwhile investment for pharmaceutical companies.

Still, people are working on fungal vaccines, and there are a few promising candidates

Regardless of the obstacles, people are working to develop fungal vaccines — and have been for decades.

To overcome the economic inviability of developing vaccines that prevent only a small number of infections, several scientists are developing vaccines that prevent multiple fungal infections — or better yet, all of them.

Norris’s group has developed a prototype targeting three fungi responsible for 80 percent of all infections in immunocompromised people: Candida, Aspergillus, and Pneumocystis. The prototype significantly reduced illness and deaths due to these infections in experimental mice and primates. A wide variety of other candidates are also being studied.

Three fungal vaccines have made it into the human clinical trial stage to date. In the early 1980s, a trial of a vaccine to prevent infections with Coccidioides — the fungus that causes valley fever — didn’t reduce infections, and produced lots of side effects. More recently, two vaccines aimed at preventing Candida (i.e., yeast) infections had good results in human safety trials, one of which went on to show promise at preventing recurrent vaginal infections in a small, placebo-controlled trial. But without an investor to take testing to the next level — a clinical trial comparing the vaccine to standard preventive therapy — development stalled out, said Dixon.

Norris said additional animal safety studies of her team’s prototype could take another year. If those go well, the next step — a safety trial in humans — would also take about a year. After that, at least several more years of work await before her team has a licensed vaccine produced at scale.

So while any progress on fungal vaccines feels momentous, it’s wise to stay grounded about the timeline of progress in this space, said Dixon. “It’s certainly going to be a while to figure out how to get the science right, to get the protection right,” he said, “and get to the goal line.”

Sourse: vox.com