As a longtime health reporter, I see new diet studies just about every week, and I’ve noticed a few patterns emerge from the data. In even the most rigorous scientific experiments, people tend to lose little weight on average. All diets, whether they’re low in fat or carbs, perform about equally miserably on average in the long term.

But there’s always quite a bit of variability among participants in these studies.

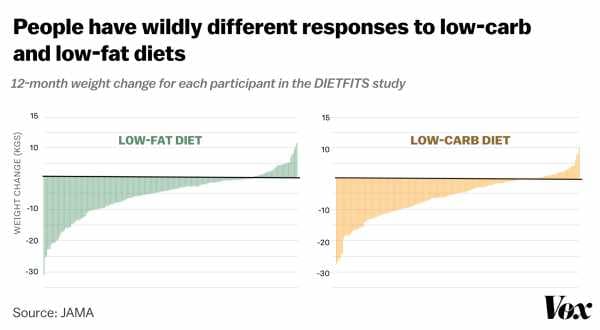

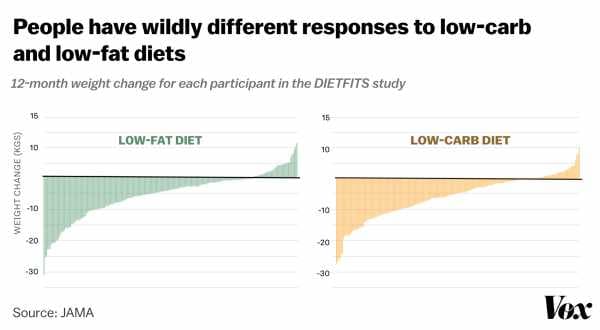

Just check out this chart from a fascinating February study called DIETFITS, which was published in JAMA by researchers at Stanford:

The randomized controlled trial involved 609 participants who were assigned to follow either a low-carb or a low-fat diet, centered on fresh and high-quality foods, for one year. The study was rigorous; enrollees were educated about food and nutrition at 22 group sessions. They were also closely monitored by researchers, counselors, and dietitians, who checked their weight, waist circumference, blood pressure, cholesterol, and other metabolic measures throughout the year.

Overall, dieters in both groups lost a similar amount of weight on average — 11 pounds in the low-fat group, 13 pounds in the low-carb group — suggesting different diets perform comparably. But as you can see in the chart, hidden within the averages were strong variations in individual responses. Some people lost more than 60 pounds, and others gained more than 20 during the year.

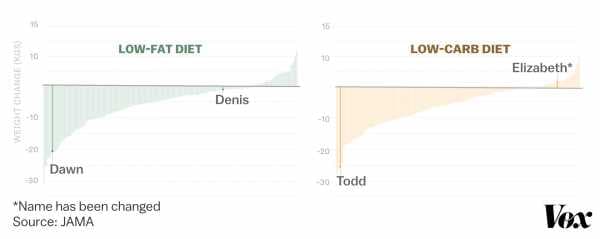

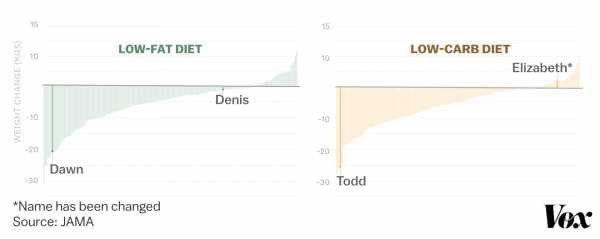

To learn more about why this happens, I asked the lead DIETFITS researcher at Stanford, Christopher Gardner, if he would introduce me to some of the study participants. Over the last week, I’ve spoken to Dawn, Denis, Elizabeth*, and Todd — two low-fat dieters and two low-carb dieters — about their experiences of succeeding or faltering in trying to slim down. Dawn and Todd lost a lot of weight on the study, while Denis lost very little and Elizabeth gained a few pounds. You can see where these participants fell on the chart here:

While these four DIETFITS enrollees are not necessarily representative of the 600-plus people who participated in the research, their stories can teach us a lot about why diets fail and succeed. As it turns out, the keys to their fate during the study had little to do with their low-fat or low-carb eating regimens. Here are four themes that emerged from our conversations.

1) Your job can make it harder — or easier — to lose weight

At the beginning of the study, Todd Moore weighed 269 pounds. After a year on the low-carb diet, he’d lost 58 pounds — making him an outlier and an incredible success.

When I asked him what contributed to all the weight loss, his answer was surprising: It was, in part, a change of job — and a big shift in daily patterns that came with it.

Todd had been working as an electrical technician for a medical company in the Bay Area when he heard about DIETFITS in 2014. His role involved a lot of manual labor — rolling around on the floor, working to repair CT scanners or X-ray machines — and he felt his weight was often getting in his way. He was also driving a lot between appointments in hospitals, often turning to burger joints or Taco Bell for fast and convenient food.

“[I’d] eat to get something in my body and go to the next spot so I could work,” said the 47-year-old father of three. “It was rushed and hurried, and not too much thought was going into what I was putting in my body.”

Joining the study “was really life-changing for me,” he said. Weight had been a problem since his childhood, but he managed to finally get to a body size he’s comfortable with — and he’s kept off the extra pounds to this day.

One of the major reasons for his success? He went from working in the field at hospitals, and spending much of the day on the road, to doing IT support from an office only two miles from his house.

“[It helped with] preparing my meals and staying focused. I had more time throughout my day when I’m not driving,” he said. That meant more time to exercise and to shop for healthier items at the grocery store.

These days, he’s no longer eating low-carb, but he follows a plant-based diet. “[There are] determining factors in our lives making us eat the way we do,” he said. And so he advises would-be dieters to reflect on how their jobs may be nudging them in unhealthy directions.

On the other end of the spectrum, Denis McComb lost only 4 pounds during the study, from a starting weight of 233. And he described how his job got in the way of his success. As a state of California safety engineer, he sits in front of a computer after what can be an hour’s drive to work, or he drives around doing field visits.

“A lot of times at work if I’m on an inspection, I’ll bring a Clif Bar with me or stop [for] fast food and grab something to eat to satisfy [my] hunger,” Denis said. “It’s hard; you have to fight every day, every inch.”

Ultimately, he says he has little time and energy for the physical activity and meal planning he knows he needs to lose weight.

2) The built environment around you matters

Elizabeth Smith* also followed the low-carb diet — but she gained 6 pounds on the study. One thing that hindered her weight loss, she thinks, is the less active lifestyle she’s adopted in America.

Twelve years ago, Elizabeth immigrated to the Bay Area from Germany with her husband and three kids — and weight gain followed. By the time of the study, the number on the scale had climbed to 191 pounds.

The reasons Elizabeth gained weight in America are clear to her: Growing up in Germany, her family rarely ate in restaurants and cooked most of their food at home. She also relied on public transit and walked a lot every day. “It’s super easy to get your 10,000 steps in in Europe,” she said. “You don’t pay attention or have to make any effort.”

In car-dependent California, she’s had the opposite experience. “I have to take at least an hour walk [at lunch] to get close to 10,000 steps,” she said. Eating healthfully outside home feels a lot more challenging too: Many of the default options are highly processed, sugary foods, served in giant portions. “It’s just so insanely exhausting to just have a relatively baseline healthy lifestyle [here],” she said.

Elizabeth didn’t shift her diet much for the study, she says. She had already been cooking a lot at home and focusing on high-quality, fresh ingredients — though she did manage to eat fewer carbs throughout the year. Still, she found it difficult to fit in regular exercise. And the study emphasized food quality rather than cutting calories — something she feels may have also contributed to her weight gain.

“I was substituting the sweet foods with super-yummy low-carb foods. I would make eggs, tomatoes, avocados, which are healthy — but if you eat too much, you’re still going to gain.”

3) Family health concerns can be a nudge to change behavior

Dawn Diaz lost 47 pounds following the low-fat diet for the study, from a starting weight of 215 pounds. And when I asked Dawn why she thinks she succeeded this time after failing in all her many previous attempts to lose weight, she told me about a specific — and very difficult — situation that helped give her extra motivation.

Just before she joined the study, one of her sisters was diagnosed with cancer. The health scare kept making Dawn think she had to find a way to live a healthier lifestyle. Around the same time, her younger daughter began struggling with an eating disorder.

“I thought, ‘I’m not setting a good example [for my daughter] by encouraging excessive food intake,’” she said.

These personal tragedies helped focus Dawn; it was no longer just about getting the number on the scale down. She wanted to fight to be healthy at a time she was seeing her sisters suffer in poor health. And she wanted to fight to be healthy for her two daughters, to set a good example for them.

Similarly, Todd mentioned a scare before joining the study. He had realized his behavior on alcohol often hurt the people around him and decided to quit drinking. “That was the beginning of what happened to me afterward,” he says.

Becoming sober made him reflect on “what kind of person I wanted to be long-term.” He realized he wanted to be a healthy dad and husband, and what he learned about his body and nutrition through the study gave him the tools to achieve that.

4) The quality of your diet may be more important than whether you’re eating low-fat or low-carb

As you can see in the chart, the participants following the low-carb and low-fat diet had virtually identical distributions of weight loss. This fact was not lost on the four participants I spoke to.

In the study, Dawn Diaz was assigned to the low-fat diet, which initially disappointed her. (She had tried the Atkins low-carb diet in the past, and it had helped her lose weight quickly.) But she soon realized focusing on the quality of the foods she was eating, and how she was eating them, probably mattered more for her in the long run than whether she was eating more carbs or fat.

“Eating whole foods [helped],” she said. “It fills you up; you feel like you’ve eaten enough. [And] I try to avoid the fast food.”

Dawn learned this from the researchers, who described quality nutrition to the study participants this way:

Dawn started planning her meals based on groceries she bought and sitting down to eat them (instead of eating in the car, as she used to). She also started organizing activities like walks or hikes with her daughters, rather than her default weekend activity of bringing them to restaurants for big meals. Overall, the study changed her relationship with food, she said.

Perhaps even more importantly, both Todd and Dawn — the pair who lost the most weight — did not feel like their new diets were hardships. They enjoyed learning about nutrition and healthy food preparation. They drew inspiration from the life circumstances they found themselves in. They felt empowered on the diet, and felt that the habits they picked up were sustainable and easy to maintain — at least for the moment.

Interestingly, the focus on quality did not work for Denis and Elizabeth, the pair who did not lose much or even gained in the study. Denis felt he had a hard time saying no to junk foods and didn’t have enough time and motivation to prepare healthy alternatives consistently. He also felt frustrated by the fact that he struggled to apply everything he learned about nutrition. Elizabeth, meanwhile, felt she could have used more advice on how to cut calories and portion sizes, instead of all the focus on eating healthy foods.

And that leads us to one of the burning mysteries of diets: how to explain why some people fail where others succeed — or the extreme variation in responses. Right now, science doesn’t have compelling answers, but the unifying theme from the four study participants should be instructive: The particulars of their diets — how many carbs or how much fat they were eating — were almost afterthoughts. Instead, it was their jobs, life circumstances, and where they lived that nudged them toward better health or crashing.

*Elizabeth asked that her name be changed to protect her privacy.

Sourse: vox.com