2023 will break more weather records as the southern hemisphere heads into spring.

Umair Irfan is a correspondent at Vox writing about climate change, Covid-19, and energy policy. Irfan is also a regular contributor to the radio program Science Friday. Prior to Vox, he was a reporter for ClimateWire at E&E News. The Vox guide to extreme heat

El Niño, the warm phase of the Pacific Ocean’s temperature cycle, has already pushed temperatures around the world to levels never recorded before. Humanity this year experienced the hottest July, the hottest August, and the hottest September ever measured across the planet.

The temperatures didn’t just inch past the prior records; they blew right through them. September’s heat beat the previous high by nearly a whole degree Fahrenheit, “a staggeringly large margin,” according to Robert Rohde, a climate scientist at Berkeley Earth.

The first global temperature data is in for the full month of September. This month was, in my professional opinion as a climate scientist – absolutely gobsmackingly bananas. JRA-55 beat the prior monthly record by over 0.5C, and was around 1.8C warmer than preindutrial levels. pic.twitter.com/mgg3rcR2xZ

— Zeke Hausfather (@hausfath) October 3, 2023

But while the northern hemisphere is cooling off as autumn sets in, it’s only getting hotter south of the equator. And around the world, El Niño is likely to continue pushing weather to greater extremes into next year.

This autumn, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration forecasted that a “strong” El Niño would persist in the northern hemisphere through March 2024, sending shock waves into weather patterns.

Historically, El Niño years tend to set new heat records, energize rainfall in parts of South America, fuel drought in Africa, and disrupt the global economy. It may already have helped fuel early-season heat waves in Asia this year.

“This will have far-reaching repercussions for health, food security, water management and the environment,” said Petteri Taalas, secretary-general of the World Meteorological Organization, in a statement in May. “We need to be prepared.”

This winter, NOAA anticipates that El Niño will contribute to drier and warmer than normal conditions across the northern continental US while causing more snow and rain across the south and much of the east coast.

Some of El Niño’s biggest effects are playing out across the southern hemisphere now. South America is emerging from one of the hottest winters ever experienced on the continent. That created the conditions fueling wildfires in Argentina’s Cordoba province that forced evacuations in October.

Awful situation unfolding right now in Villa Carlos Paz, Argentina as a fast-moving wildfire is approaching the city. Multiple structures on fire. Urgent evacuations are underway. pic.twitter.com/6741nRG2ZV

— Nahel Belgherze (@WxNB_) October 10, 2023

“In Central Argentina there is an enormous lack of precipitation, and unfortunately, the forecast says there will be no rain in coming days,” Matilde Rusticucci, a professor of atmospheric sciences at the University of Buenos Aires, wrote in an email. However, through the rest of the year, El Niño is likely to bring downpours to the country as spring turns to summer, said Rusticucci, who also works as a researcher at Conicet, Argentina’s national science research council. That would alleviate fire conditions, but could lead to flooding.

This El Niño will likely be costly to the global economy. The one in 1997-98, one of the most powerful in history, led to $5.7 trillion in income losses in countries around the world according to a study published in May in the journal Science. That’s much higher than prior estimates of as much as $96 billion. It was also blamed for contributing to 23,000 deaths as storms and floods amped up in its wake.

Rising average temperatures are poised to amplify these effects further. Even if every country met its existing pledges to cut greenhouse gas emissions to limit climate change, El Niño events could lead to $84 trillion in economic losses by the end of the century, according to the Science study.

“[T]hese findings together suggest that while climate mitigation is essential to reduce accumulating damages from warming, it is imperative to devote more resources to adapting to El Niño in the present day,” the authors wrote.

This might seem like a whole lot of impact from a weather phenomenon driven by slightly warmer than average water in the Pacific. But it turns out that the planet’s largest ocean, covering about one-third of its surface, is a powerful engine for weather around the world. Seemingly small shifts in temperature, wind, and current in the parts of the Pacific Ocean near the equator can alter weather patterns for months.

Scientists have improved their ability to predict when these cycles will rise and how severe they will be, buying us time to prepare. Yet humans are also changing the climate while building more ports, homes, and offices in areas that are vulnerable to disasters worsened by El Niño. That’s why such events can be so costly — but there are measures that can dampen some of their worst effects.

How does El Niño work?

Fishers off the coast of Ecuador and Peru coined the term El Niño in the 19th century to describe a warm water current that regularly built up along the west coast of South America around Christmas (“El Niño” means “the boy,” a reference to the Christ child.)

The warm water turned out to be part of a much larger complicated system connecting seas and skies all over the world. Scientists now know that the Pacific Ocean cycles between warm, neutral, and cool phases roughly every two to seven years, inducing changes in the ocean and in the atmosphere. This back-and-forth is called the El Niño Southern Oscillation, or ENSO. It’s “the strongest fluctuation of the climate system on the planet,” said Michael McPhaden, a senior scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). (You can read a more detailed explanation of El Niño’s mechanics here.)

The key thing to understand is that the Pacific Ocean is huge. Huuuuge. Huuuuuuuuge. And that’s just the surface area; the Pacific averages 13,000 feet in depth but can dip as low as 36,000 feet. Water isn’t just moving north, south, east, and west, but up and down. These currents are driven by wind as well as temperature and salt gradients.

Earth’s oceans also act as a giant thermal battery. They’ve absorbed upward of 90 percent of the warming humans have induced from burning fossil fuels, and the Pacific, at least, appears to be warming particularly fast.

All this adds up to a world-changing amount of energy packed into one big ocean.

During ENSO’s neutral phase, wind pushes warm water in the Pacific around the equator from east to west. This lets warm water pool near Indonesia and raises sea levels there by 1.5 feet (0.5 meters) above normal compared to the coast of South America. The warmer water near Asia evaporates more readily and fuels rainstorms there. And as surface waters get pushed away from South America, water from deeper in the ocean rises, bringing with it valuable nutrients like phosphorus and nitrogen. This phenomenon is called upwelling, and it’s critical for nourishing sea life. About half the fish in the world are caught in upwelling zones.

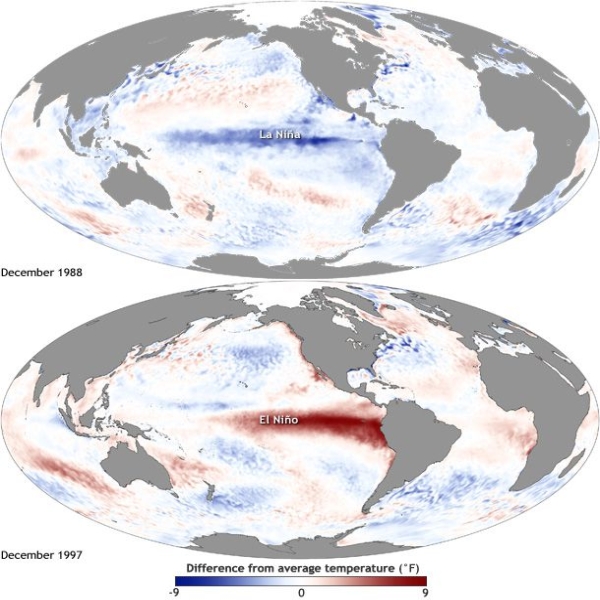

When El Niño starts picking up, this engine shifts gears. The trade winds slow down and the warm water near Asia starts sloshing back eastward across the Pacific, reaching the coast of South America. The drift in warm water also moves evaporation and rain such that southeast Asia and Australia tend to get drier while Peru and Ecuador typically see more precipitation.

“It creates a lot of convection and a lot of thunderstorms in a part of the world that doesn’t always have that activity,” said Dillon Amaya, a research scientist at NOAA. “You release a lot of energy and a lot of heat into the atmosphere and this creates waves that propagate in the Northern Hemisphere and in the Southern Hemisphere symmetrically.”

These perturbations can then deflect weather patterns across the world. For instance, in the US, El Niño typically leads to less rainfall in the Pacific Northwest and more in the Southwest. But it’s one of several factors that influences the weather, making it tricky to anticipate just how it will play out in a given year. “It’s not always a one-to-one relationship,” Amaya said.

The guidelines for declaring an El Niño are sea surface temperatures in the equatorial Pacific that stay 0.9 degrees Fahrenheit (0.5 Celsius) above the 30-year average for three months. The signal can be obscured by the noise of the changing seasons. That’s why scientists waited until June to say for certain that the world is in an El Niño year. “Once you get on the other side of spring, our forecast skill goes way up,” Amaya said.

This engine can also shift into reverse. Tradewinds blowing east to west across the Pacific get stronger, cooling the region around the equator, a phenomenon known as a La Niña. This tends to have a cooling effect over the whole planet.

What can we expect this year?

El Niño typically picks up over the summer and shows its strongest effects over the winter in the Northern Hemisphere. This year, forecasts drawing on ocean buoys, sensors, satellite measurements, and computer models showed that a strong one was brewing as the eastern Pacific Ocean steadily warmed up just below its surface.

“The vast majority … are assuming that we’re going to have a big El Niño this winter,” said Amaya. “I think we’re definitely expecting to break global temperature records this year.”

Part of what’s making this so jarring is that ENSO is coming out of an unusually long La Niña phase. They typically last one to two years, but the world has been in one since 2020. “There’s only been three triple-dip La Niñas in the last 50 years: One in 1973 to 76, one from 1998 to 2001, and then this one,” said McPhaden. That has allowed more heat energy to accumulate in the ocean and may have helped cushion some of the warming due to climate change. However, the World Meteorological Organization noted that the past eight years were still the hottest on record.

So the warming water detected in the equatorial Pacific and the rebound from La Niña pointed toward a strong El Niño. “All the ingredients are in place and the soup is cooking,” McPhaden said. “The ocean is uncorked. All that heat that was stored below the surface of the ocean is going to come out.”

The other big factor is that the planet itself is heating up. El Niño is part of a natural cycle. Human activity is amplifying some aspects of it, but not always in a straightforward way. Researchers expect that climate change will increase the chances of strong El Niño and La Niña events, but are still chalking out how they will manifest. Exactly how that extra heat is distributed across the ocean and the atmosphere will alter which regions see more rain, which ones will suffer drought, and where the biggest storms will land.

And while the rising El Niño this year will eventually cycle back to its cool phase, it won’t be enough to offset humanity’s consumption of fossil fuels. “What really matters from the long-term point of view is this relentless rise in greenhouse gas concentrations,” McPhaden said. “You cannot escape that there will be continued warming because of that.”

These forecasts, however, buy precious time to prepare. While El Niño can push some disasters to greater extremes, tools like early warning systems, disaster shelters, evacuations, and climate-resilient building codes can keep the human toll in check. It’s going to be an extreme year, but it doesn’t have to be a deadly one.

Update, October 12, 2 pm: This story was originally published on May 30 and has been updated with new temperature records and NOAA’s updated El Niño forecast.

Source: vox.com