Part of

Understanding the Trump era

President Donald Trump is a Republican. But often, and more so than any president in memory, he lacks a consistent political ideology.

During the campaign, Trump took five different positions on abortion in three days. On other issues, his policy preferences have been clear as mud: “I don’t want to have guns in classrooms, although in some cases, teachers should have guns in classrooms, frankly,” he told Fox News in 2016.

And where he is more consistent — like in his deference to Russian President Vladimir Putin, most stunningly in the recent joint press conference in Helsinki — he is often at odds with many prominent figures in his own party.

All this makes this period of history extremely interesting for political scientists and psychologists to study.

“We’ve never had a federal elected official, let alone the leader of a party or the president of the United States, who is so easily moved from one position to another without offering any sort of justification or apology or explanation,” Michael Barber, a political scientist at Brigham Young University, said last year.

“It’s very hard to find instances where prior policy views seem to drive later voting or decisions”

Researchers like him have long tried to understand the power of leaders and the willingness of the public to hold them accountable. And rarely do they get a real-life experiment like Trump to help them answer some huge questions at the heart of democracy:

How much power do presidents have in swaying public opinion? Will the base always follow even if a president swings wildly from one position to another?

And there’s another key question at play here that matters a lot for the future of Trump’s presidency: If prominent Republican leaders start breaking away from Trump because they don’t like his ideas or temperament, will the base also break?

In essence, Trump is providing an unprecedented opportunity to test the “follow the leader” theory of political science — and to see if Trump will push his followers to a breaking point.

The research here predicts there won’t be a pivotal moment where Republicans around the country stop supporting Trump en masse. Polls show it too. An Axios/SurveyMonkey poll released July 19 found that 79 percent of Republicans approved of Trump’s press conference with Putin. And they approved despite the overwhelmingly negative press that followed it, and even after prominent Republicans — like Sen. John McCain, a former GOP presidential nominee — were harshly critical.

Voters will follow their leader. Trump gives political scientists the chance to find out how far.

A recent experiment found Republicans are more likely to adopt liberal policies when Trump supports liberal policies

Yes, Trump has been extremely consistent in some areas: He’s made policies that make it harder for people who live in Muslim-majority nations to enter the United States, he shares Republican animosity toward Obamacare, and he’s reducing the role of the Environmental Protection Agency and other federal agencies. But for a president, Trump is historically scattershot.

In January 2017, Barber and his BYU colleague Jeremy Pope designed an experiment to take advantage of that fact. Its publication is forthcoming in the political science journal the Forum. In their test, they wondered: Are Trump’s supporters ideological, or will they follow him wherever his policy whims go? Right after Trump’s inauguration, they ran an online experiment with 1,300 Republicans.

The study was pretty simple. Participants were asked to rate whether they supported or opposed policies like a higher minimum wage, the nuclear agreement with Iran, restrictions on abortion access, background checks for gun owners, and so on. These are the types of issues conservatives and liberals tend to be sharply divided on.

Barber and Pope wondered: Would Republicans be more likely to endorse a liberal policy if they were told Donald Trump supported it?

One-third of the participants read statements where they were told Trump supported a liberal position, like this:

The control group of the experiment saw these questions, but they didn’t mention Trump. And another arm of the experiments tested what happened when Trump was said to support conservative policies.

The answer: “On average, across all of the questions that we asked, when presented with a liberal policy, Republicans became about 15 percentage points more likely to support that liberal policy” when they were told Trump supported it, Pope says. They follow their leader. “The conclusion we should draw is that the public, the average Republican sitting out there in America, is not going to stop Trump from doing whatever he wants.” The effect even held true on questions about immigration. If Trump supported a lax immigration policy, his supporters said they did too.

Past experiments with liberal participants have found a similar effect: Liberals are more likely to support conservative policies when told their leaders support conservative policies. And even creepier: other research in psychology finds that people aren’t always consciously aware when they change their minds in this manner. That is, it’s possible we forget what we once believed when our ideological stances change.

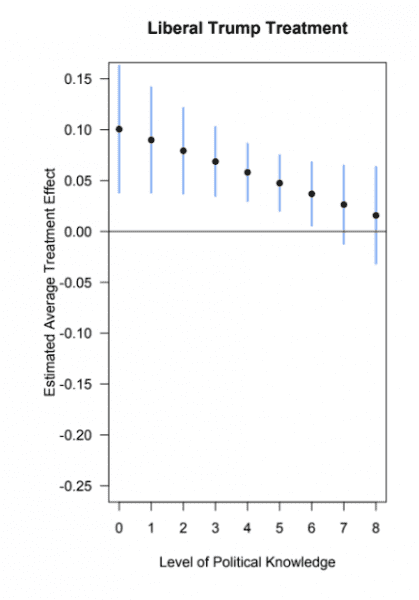

It’s important to note that not everyone is so easily swayed by their leaders. In their study, Barber and Pope found the people most likely to follow Trump’s lead were those who didn’t know much about politics but still strongly identified as Republicans. The most knowledgeable in their sample were hardly swayed at all. To a certain extent, the effect may be the result of people not thinking too hard when filling out a questionnaire. But then again, that’s how most of us come to our political opinions: by not thinking too hard about them.

There are real-life examples of this leadership-down process of opinion that go back years. In 1971, Republican President Richard Nixon made a surprise decision to impose a 90-day freeze on wages and prices (to halt inflation, a move that runs counter to conservative economic policy), and even ardent conservative supporters followed suit.

“A Columbia survey … found a 45-point increase from 32 percent to 82 percent ‘virtually overnight’ among Republican activists — precisely the people who ought to have been most resistant to the policy shift on ideological grounds,” explains Larry Bartels, a political scientist at Vanderbilt University and a leading expert on how public opinion forms.

Other research has found that many of us will change our opinions after merely learning that a leader supports an idea.

In 2014, political scientists David Broockman and Daniel Butler conducted a field experiment where they had real state legislators’ offices send letters to constituents who the researchers knew, via another survey, disagreed with the legislators’ policies. The letters simply stated what the legislators believed. A control group got no letters. The letters were sent by Democratic lawmakers, but they didn’t state their affiliation in the letters.

The letters — sent to people regardless of the political affiliation — made a small but meaningful effect. They “caused the voters who disagreed with the legislator to become about 6.5 percentage points more likely to agree with the legislator,” Broockman and Butler wrote.

A follow-up experiment added another variable to the mix: Some of the constituents got letters that contained lengthy explanations of their leaders’ policy views. Others just got short summary statements. And “constituents who received lengthy arguments from legislators justifying their positions were just as likely to change their opinions as constituents to whom legislators provided little justification,” they wrote.

The experiment is a demonstration that it doesn’t take all that much to get voters to flip-flop their political opinions. They might not even realize they’re doing it at all.

Trump may have caused some massive swings in public opinion among Republicans

Consider this recent one.

In 2015, just 12 percent of Republicans held a favorable view of Russian President Vladimir Putin, according to Gallup. It’s not surprising this figure was so low. Just three years earlier, Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney had declared Russia to be our “top geopolitical foe.”

Flash-forward to 2017. Then, 32 percent of Republicans had a favorable view of Putin, according to Gallup. That’s a huge jump. And during that time, if anything, Putin lived up to Romney’s prediction.

What changed in just two years? Donald Trump, and his reluctance to criticize the Russian leader.

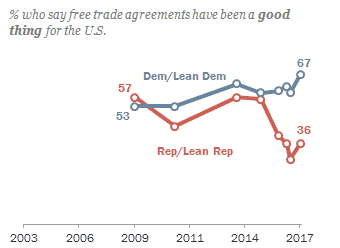

Or take the issue of free trade: Typically conservatives are in favor of it. It lowers costs for American businesses that want to outsource labor or buy materials from overseas.

“Since Donald Trump entered the 2016 presidential campaign by descending a golden escalator, Republican support for free trade has similarly declined,” Barber and Pope write in their paper. As Pew finds, from 2015 to 2017, Republican support of free trade plummeted from 56 percent in support in 2015 to just 36 percent in 2017. That’s a 50 percent change in opinion.

Trump has massive power to sway public opinion among his followers.

In March 2017, a CBS poll found that 47 percent of Americans — and a full 74 percent of Republicans surveyed — believed it’s “likely” or “somewhat likely” that President Trump’s offices were wiretapped during the 2016 presidential campaign. Trump had tweeted that “Obama had my ‘wires tapped’ in Trump Tower” during the campaign. But there was no credible evidence this happened.

Since then, it was revealed that Trump’s former campaign manager Paul Manafort had been under surveillance, which confuses the matter. Still, Trump said it happened, and many believed.

And there’s an opposite of the follower-the-leader effect at play too. When Trump takes a position on something, liberals are sure to oppose it. Vox’s Matthew Yglesias has documented these swings in public opinion here.

Very few people have stable policy views. They do have stable party affiliations.

We have a vision of democracy where a virtuous public steers the decisions of leaders, Barber says. But over and over again in experiments — and in the real world — that vision turns out to be a mirage.

The researchers I spoke to admit there’s a bit of a chicken-and-egg problem in this research. Can we really know that Trump caused the change of opinion on free trade, or did Republican voters change their minds and then endorse an anti-free trade candidate?

Both seem to be going on. But there’s a compelling case that Trump caused it.

Gabriel Lenz, a political scientist at UC Berkeley and author of Follow the Leader? How Voters Respond to Politicians’ Performance and Policies, has analyzed decades’ worth of data from the American National Election Studies, a long-running study assessing voter preferences and knowledge about politics. The study data allows Lenz to track the very same voters over decades of political change.

One of the biggest findings in all this data: Voters aren’t all that knowledgeable about politics. Lenz finds only 50 percent of the public can accurately match policy preferences to the correct party or candidate. And about 20 to 40 percent of the public holds stable views on policy, Lenz finds in a forthcoming paper in the Journal of Politics.

“A lot of people don’t know how the parties describe themselves,” he says. “And when they learn my party’s conservative [or is against free trade, etc.], they start saying they’re conservative too. … It’s very hard to find instances where prior policy views seem to drive later voting or decisions.”

A lot of us are like Trump in that regard.

In his research, Lenz finds some people are more likely to be consistent on certain topics, like marijuana legalization, abortion access, and anything related to racial identity. But overall, “we have ample evidence that people are amazingly good at ignoring contradictions.” People can say they support free trade one year and say they’re against it the next, and not really notice their opinion has changed.

That’s partly because when people answer public opinion polls, they rely on mental shortcuts. They may replace a hard question (“How do I feel about international trade taxes?”) with an easy question (“What team am I on, and how would they answer this question?”).

“These shortcuts can be political ideology; it could be religiosity, deference to scientific authority,” Dominique Brossard, a psychologist who studies public opinion at the University of Wisconsin, said in an interview last year. “People don’t see themselves as being irrational doing this.”

One reason Trump is particularly influential: he’s a “toxic meme” machine

Trump has a powerful ability to sway opinions among his base — and create polarized opinions among his detractors. We see this play out all the time.

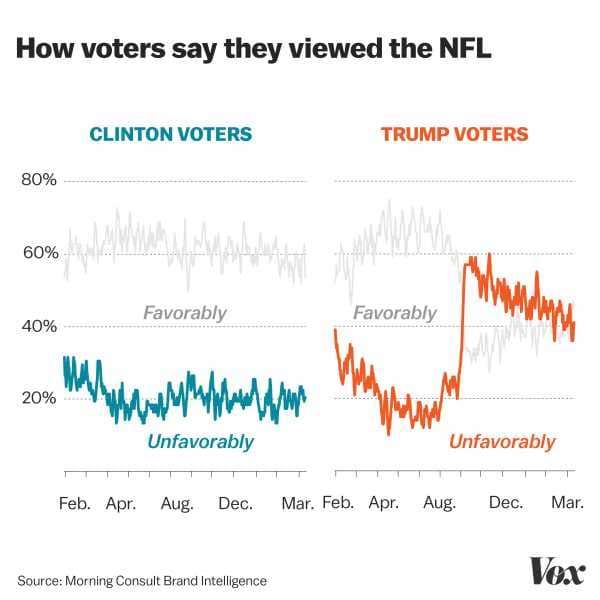

Think about the fall 2017 fracas calling out NFL players protesting the national anthem.

The message to Trump’s base is clear: Only ungrateful un-Americans would dare protest the national anthem. His supporters — many of whom perhaps haven’t even been paying attention to the anthem controversy — will believe that too.

When Trump comes out with a strong opinion on a subject, it’s a signal to his base saying, “This is what we believe.” He draws a clear line of what’s “good” and what’s “disgraceful.” It draws a massive amount of attention to a subject, and drives a wedge.

A common Trump tactic is to take something nonpolitical, or not always obviously political (like the NFL) and use it to turn people against another. This isn’t to say there’s nothing worth debating or caring about in the NFL protests. Trump just amps up the temperature in a way that’s sure to pit people against one another.

As Yale professor Dan Kahan puts it, Donald Trump is a “toxic meme” generator.

Toxic memes are stories or ideas “that are predictively likely to trigger the sense that it is us against them,” Kahan explained earlier this year at a scientific conference. “The special danger of Donald Trump,” he said, “is that he can drag issues across this line. He’s the president of the United States. He’s going to get publicity for these kinds of statements, ones that he knows will end up dividing people.”

After Trump directed a massive amount of attention toward the NFL protests, and became so outspoken about it, look at what happened.

Nearly overnight, Trump supporters began to express strong negative feelings about the league. Yes, that’s conservative Americans expressing a dislike of football. Hard to imagine in a previous time.

All political leaders have the ability to polarize. But few have done what Trump has done: built a massive social media presence around drawing stark lines between the people who believe in “Make America Great Again” and the “losers” who don’t.

Trump makes it exceedingly clear to followers where their opinions on matters like the NFL anthem protests, Obamacare, and other weighty matters should lie. He’s a master at tying these issues to a proud American identity. If you identify as a proud patriot, and are told that patriots despise NFL owners who let players kneel during the anthem, you’re going to despise them too.

Prominent Republicans and conservatives have spoken out against Trump. It’s (probably) not enough to break Trump’s influence over Republicans.

Politicians are usually ideological. They usually conform nicely to what the party believes. There haven’t been too many tests (aside for the ones mentioned above) of the follow-the-leader theory in the real world. “It’s so rare for a leader of a party to come out and say, ‘We’re going to do this thing the base doesn’t like,’” Barber says.

It’s tempting to imagine a scenario in which Trump’s base leaves him — that if enough prominent Republican leaders and conservative thinkers make a clear, damning break with the president, they can lead Trump’s followers to a more ideologically pure pasture. In that scenario, Republicans hold on to their group identity while decrying Trump as a betrayer.

But let’s not hold our breath and wait for the moment when the Trump base leaves him en masse, though it would be a fascinating moment for political science if that happens. Still, 88 percent of Republicans approve of the job Trump is doing in the latest Gallup tracking poll.

For now, here’s what the political psychology suggests: A mass exodus ain’t going to happen. Recently, Broockman and his colleague Josh Kalla published a meta-analysis on 49 field experiments in which campaigns attempted to sway voters’ minds. They found evidence that voters’ opinions on issues can change, but not their opinions on candidates. That is to say: There’s scant scientific evidence to say that door-to-door political campaigns can dissuade voters from liking their chosen leader.

It’s also not certain that prominent Republicans could be the catalyst to lead a revolt. In their experiment, Barber and Pope found no evidence that “congressional leaders” could sway Republicans to adopt liberal views. The trick only worked with Trump’s name.

“Only the most vocal, loudest messages come through, and on that, it is hard to beat the president,” Lenz says.

Sourse: vox.com