The vernal equinox is upon us: On Thursday, March 19, both the Northern and Southern hemispheres will experience roughly an equal amount of daylight. For those of us in the Northern Hemisphere, it marks the beginning of spring, with daylight hours continuing to lengthen until the summer solstice in June. For those south of the equator, it’s the beginning of autumn.

Technically speaking, the equinox occurs when the sun is directly in line with the equator. This will happen at 11:49 pm Eastern on Thursday. (With the equinox occurring so close to midnight, I’d argue to can choose to celebrate either today or tomorrow.)

This year’s equinox comes at a tough time, with a pandemic forcing many people to stay away from the people and activities they love. Maybe it helps to know that nature will still go on as planned. Flowers will still bloom, temperatures will still rise, and sunsets will creep later and later into the evening.

Below is a short scientific guide to the equinox.

1) Why do we have an equinox?

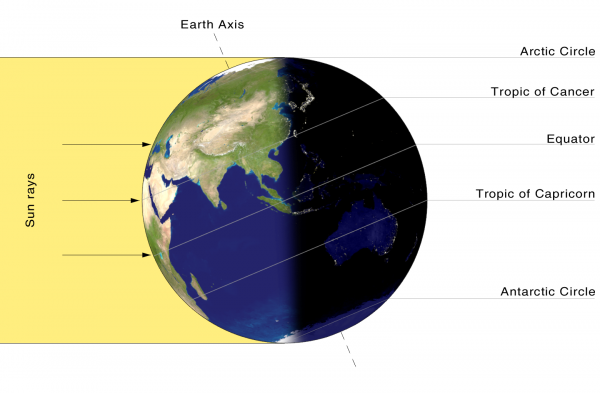

The equinox, the seasons, and the changing length of daylight hours throughout the year are all due to one fact: The Earth spins on a tilted axis.

The tilt — possibly caused by a massive object hitting Earth billions of years ago — means that for half the year, the North Pole is pointed toward the sun (as in the picture below). For the other half of the year, the South Pole gets more light. It’s what gives us seasons.

Here’s a time-lapse demonstration of the phenomenon shot over the course of a whole year from space. In the video, you can see how the line separating day from night swings back and forth from the poles during the year.

And here’s yet another cool way to visualize the seasons. In 2013, a resident of Alberta, Canada, took this pinhole camera photograph of the sun’s path throughout the year and shared it with the astronomy website EarthSky. You can see the dramatic change in the arc of the sun from December to June.

(You can easily make a similar image at home. All you need is a can, photo paper, some tape, and a pin. Instructions here.)

2) How many hours of daylight will I get Thursday?

Equinox literally means “equal night.” And during the equinox, most places on Earth will see approximately 12 hours of daylight and 12 hours of night.

But not every place will experience the exact same amount of daylight. For instance, on Thursday, Fairbanks, Alaska, will see 12 hours and 13 minutes of daylight. Key West, Florida, will see 12 hours and six minutes. The differences are due to how the sunlight gets refracted (bent) as it enters Earth’s atmosphere at different latitudes.

That daylight is longer than 12 hours on the equinox is also due to how we commonly measure the length of a day: from the first hint of the sun peeking over the horizon in the morning to the last glimpse of it before it falls below the horizon in the evening. Because the sun takes some time to rise and set, it adds some extra daylight minutes.

Check out TimeAndDate.com to see how many hours of sunlight you’ll get during the equinox.

3) Is the equinox really the first day of spring?

Well, depends: Are you asking a meteorologist or an astronomer?

Meteorologically speaking, summer is defined as the hottest three months of the year, winter is the coldest three months, and the in–between months are spring and fall.

Here’s how the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration breaks it down:

Astronomically speaking, yes, winter begins on the winter solstice.

Meteorologically speaking, spring for many parts of the US came very early this year (due to that other crisis):

4) Over the entire year, does every spot on Earth get an equal number of daylight hours?

In the summer months, the northernmost latitudes get a lot of daylight. Above the Arctic Circle, during the summer, there’s 24 hours of daylight. In the winter, the Arctic Circle is plunged into constant darkness.

So does this mean the number of daylight hours — in total, over the course of the year — equal out to places where the seasonal difference is less extreme?

The answer to this question is somewhat surprising: Roughly speaking, everywhere on Earth sees a similar number of daylight hours every year. But the equator actually gets slightly fewer daylight hours than the poles.

As astronomer Tony Flanders explained for Sky & Telescope magazine, sunlight at the poles gets refracted more than sunlight at the equator. That refracting results in the visible disk of the sun being slightly stretched out (think of when the full moon is near the horizon and looks huge — it’s being refracted too). And the refracted, stretched-out sun takes slightly longer to rise and set. Flanders estimated that the equator spends around 50.5 percent of its year in sunlight, while the poles spend between 51.5 and 53 percent of their years in sunlight.

And, of course, this is how much sunlight these areas could potentially receive if the weather were always perfectly clear; it’s not how much sunlight they actually see, nor the strength of the sunlight that hits their ground. “Where are the places on Earth that receive the largest amount of solar radiation?” is a slightly different question, the answer to which can be seen on the chart below.

5) Can I really only balance an egg on its tip during on the equinox?

Perhaps you were told as a child that on the equinox, it’s easier to balance an egg vertically on a flat surface than on other days of the year.

The practice originated in China as a tradition on the first day of spring in the Chinese lunar calendar in early February. According to the South China Morning Post, “The theory goes that at this time of year the moon and earth are in exactly the right alignment, the celestial bodies generating the perfect balance of forces needed to make it possible.”

This is a myth. The amount of sunlight we get during the day has no power over the gravitational pull of the Earth or our abilities to balance things upon it. You can balance an egg on its end any day of the year (if you’re good at balancing things).

6) Is there an ancient monument that does something cool during the equinox?

During the winter and summer solstices, crowds flock to Stonehenge in the United Kingdom. During the solstices, the sun either rises or sets in line with the layout of the 5,000-year-old monument. And while some visit Stonehenge for the spring equinox too, the real place to be is in Mexico.

That’s because on the equinox, the pyramid at Chichen Itza on the Yucatan Peninsula puts on a wondrous show. Built by the Mayans around 1,000 years ago, the pyramid is designed to cast a shadow on the equinox outlining the body of Kukulkan, a feathered snake god. A serpent-head statue is located at the bottom of the pyramid, and as the sun sets on the day of the equinox, the sunlight and shadow show the body of the serpent joining with the head.

This is easier to see in a video. Check it out below.

7) Are there equinoxes on other planets?

Yes! All the planets in the solar system rotate on a tilted axis and therefore have seasons. Some of these tilts are minor (like Mercury, which is tilted at 2.11 degrees). But others are more like the Earth (tilted at 23.5 degrees) or are even more extreme (Uranus is tilted 98 degrees!).

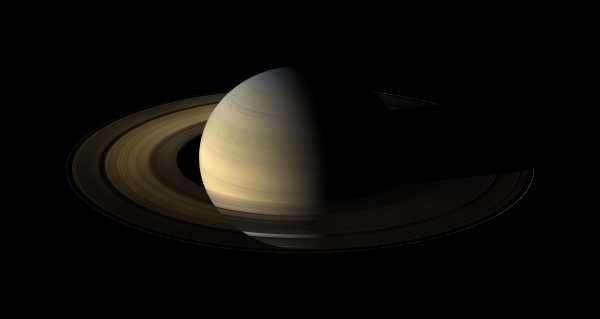

Below, see a beautiful composite image of Saturn on its equinox captured by the Cassini spacecraft (RIP) in 2009. The gas giant is tilted 27 degrees relative to the sun, and equinoxes on the planet are less frequent than on Earth. Saturn only sees an equinox about once every 15 years (because it takes Saturn 29 years to complete one orbit around the sun).

During Saturn’s equinox, its rings become unusually dark. That’s because these rings are only around 30 feet thick. And when light hits them head on, there’s not much surface area to reflect.

8) I clicked this article accidentally and really just want a mind-blowing picture of the sun

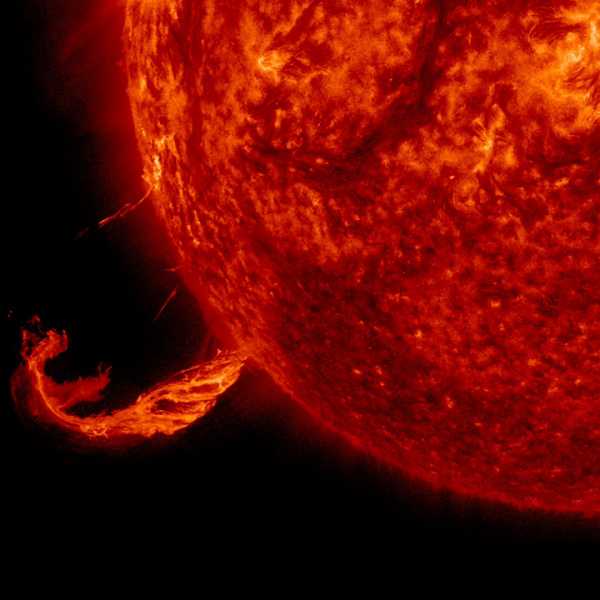

The image above was taken by NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory, a spacecraft launched in 2010 to better understand the sun.

In 2018, NASA launched the Parker Solar Probe, a spacecraft that will come within 4 million miles of the surface of the sun (much closer than any spacecraft has been before). The goal is to study the sun’s atmosphere, weather, and magnetism and figure out the mystery of why the sun’s corona (its atmosphere) is much hotter than its surface. Still, even several million miles away, the probe will have to withstand temperatures of 2,500 degrees Fahrenheit.

It’s essential to understand the sun: It’s nothing to mess with. Brad Plumer wrote for Vox about what happens when the sun erupts and sends space weather our way to wreak havoc on Earth.

Sourse: vox.com