It’s going to get very, very, very cold for millions of people across the Midwestern United States this week.

Fargo, North Dakota, for example, is expected to hit an overnight low of minus 33 degrees Fahrenheit on Wednesday. At that temperature, vodka freezes solid. The daytime high is forecast to be a frigid -18°F. Chicago, which is home to 2.7 million people, might hit a low of -22°F on Wednesday as well.

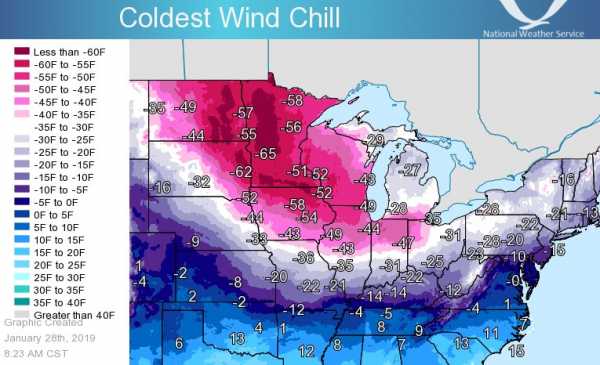

The windchill — a measure of frostbite risk that combines wind speed and air temperature — is expected to drop even lower across the region, into the negative 60s. At that windchill, frostbite sets in on exposed skin in just five minutes. It’s a dangerous situation; cold temperatures can be deadly.

“Dangerous, potentially life-threatening extreme cold and wind chills are expected,” the Des Moines office of the National Weather Service warns. “This is the coldest air many of us will have ever experienced.”

The forecast continues: “This is not a case of ‘meh, it`s Iowa during winter and this cold happens.’ These are record-breaking cold air temperatures, with wind chill values not seen in the 21st century in Iowa.”

The coldest air is expected to push through the region from Tuesday to Thursday, and it is likely to break records across the region. Overall, the Washington Post reports, the cold outbreak will hit 87 million Americans over the next few days.

But why is this cold blast happening? Blame the “polar vortex.” That’s the mass of frigid air that usually circulates in the Arctic and is dipping southward into the continental US this week.

Here’s what you need to know about it.

How the polar vortex works

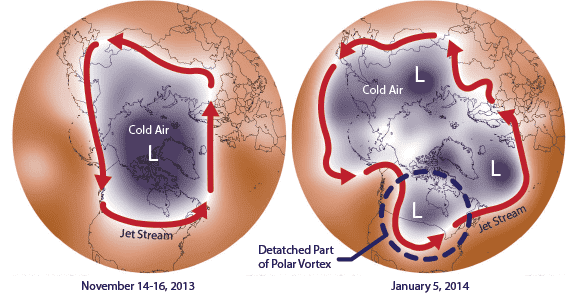

The term “polar vortex” was popularized in 2014 when a particularly brutal January cold snap sent the country into a deep freeze. Babbitt, Minnesota, reached a low of -37°. The low of 4° in New York City broke a 118-year record.

But while the name sounds dramatic, the polar vortex isn’t anything out of the ordinary or all that new.

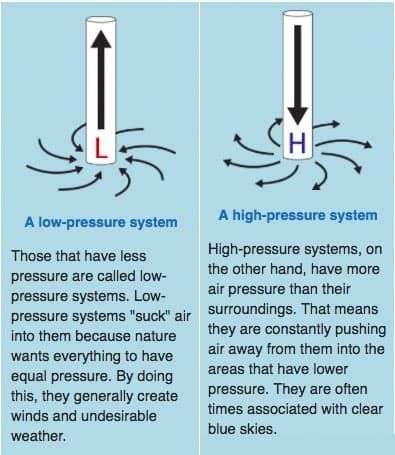

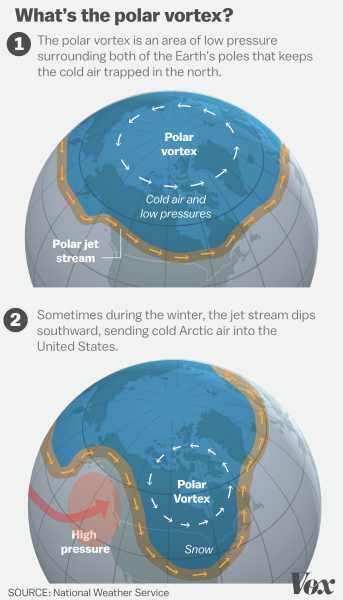

When meteorologists talk about the “polar vortex,” they’re talking about the mass of cold, low-pressure air that consistently hovers over the Arctic. It’s called a “vortex” because it spins counterclockwise like a hurricane does.

“It ALWAYS exists near the poles,” the National Weather Service emphasizes on its website.

Usually this mass of cold polar air remains, well, over the North Pole — because it’s usually strong, centered, and compact.

But sometimes the vortex weakens.

A weak vortex means colder weather in the mid-latitudes, as lobes of the vortex start to creep away from the Arctic region. (There’s also a second polar vortex a bit higher up in the atmosphere that impacts our weather less often, as the Washington Post explains.)

The weak vortex influences the path of the jet stream, an area of fast-moving air high in the atmosphere. A weak vortex can cause the jet stream to wobble southward, bringing the cold polar air down with it.

The vortex weakens, in part, because of warming temperatures in the stratosphere, as the Weather Underground explains. (There is evidence that with climate change, these polar vortex intrusions into the more southern latitudes may become more common.) And the shape of its southward intrusion is influenced by high-pressure systems.

In 2014, “the polar vortex suddenly weakened, and a huge high-pressure system formed over Greenland,” NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory explains on its website. “The high-pressure system blocked the escape of all that cold air in the jet stream, and allowed part of the polar vortex to break off and move southward.”

Again, this isn’t all that unusual. “Many times during winter in the Northern Hemisphere, the polar vortex will expand, sending cold air southward with the jet stream,” the NWS explains. “This occurs fairly regularly during wintertime.” The 2014 polar vortex was notable because it recurred throughout the winter months and into early spring, setting record low temperatures through March.

Sourse: vox.com