Sometimes things don’t work out as planned. According to a new study, this is one of the key lessons of the crisis of opioids.

Now, the history of opioid epidemic are well known: in the 1990-ies, drug manufacturers aggressively marketed opioids, especially Purdue Pharma recently released Oxycontin, which the company suggested is safer and less prone to abuse than other opioids.

This contributed to the explosion in opioid drugs, which led to more drug abuse and inviting people dependent on opioids, have led to greater use of other opioids, such as heroin and fentanyl illegal. Today the country is mired in its deadly crisis, drug overdose, ever, with tens of thousands die as a result of drug abuse and addiction each year.

One of the key reasons Purdue was able to sell his product as a safer was based on an apparent miscalculation in how people will use your drug. Oxycontin has been described as “extended release” product — opioids should be released in the system within 12 hours after the pill was taken. This, in theory, should have been Oxycontin less prone to abuse, as opioid dose in the tablets will slowly take effect.

But people have found a way out of this situation. Crush the pill to snort it or diluting it to give it, they could take the entire opioid dose in the pill Oxycontin almost instantly. The drug became profitable for people dependent on opioids, many legal ways to getting a high.

Reviews

How to stop the deadly crisis of drug overdose in American history

In 2010, Purdue was trying to put an end to it, replacing the old Oxycontin with “abuse deterrent” formula. When this new Tablet is crushed, it turns into a gummy-like substance, making it more difficult to snort or inject. It doesn’t exclude the possibility of abuse — tablets can still be used to get high by ingesting it orally, and there are ways to circumvent the process of redrafting keep ingesting it by other means. But this has made the process to abuse her a little harder.

A new working paper from researchers William Evans, Ethan Lieber, and Patrick power, says that it is indeed possible, did oxytocin less prone to abuse — but with a deadly side effect: as people decided Oxycontin was too much trouble, some former Oxycontin users turned to heroin. The subsequent increase of deaths from heroin overdose might have been enough, the researchers claim to match or even outweigh all the good that the reformulation of Oxycontin made in preventing deaths from overdose of painkillers — at least in the short term.

The medication expert in the field of politics not related to the conduct of the study warn that the findings do not mean that the revision of Oxycontin (or other extended-release opioids) was a bad idea — he did, after all, appear to make the addictive drug less prone to abuse. But a new study suggests that when it comes to combating the opioid crisis, simply reducing the use of opioid painkillers is not enough.

What the study showed

A study that was not peer not yet considered, to use economic models to assess trends in mortality from opioid overdose — smashing them to focus on character — to see what happened after the revision of oxytocin was introduced in 2010.

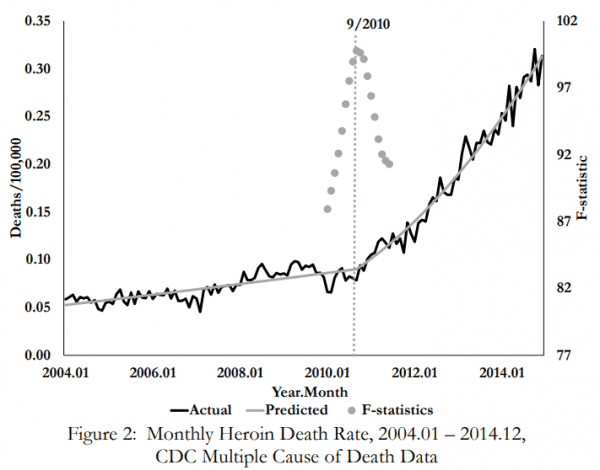

The article came to the conclusion that there was a break in trend starting in August 2010, when the language was introduced. Most importantly, the death rate from heroin overdose have started to grow faster then a month.

“Hope was the reformulation difficult to abuse, so at least we would stop the growth of mortality from opiates,” Lieber, one of the study’s authors, told me. “But instead of really see what happened, it seems, many people turned to heroin and other drugs. Because heroin is particularly dangerous, the actual opioid mortality rates — if you include the heroin — in fact, not been affected by the restatement.”

There were other indications that the language was influenced, according to the newspaper: “a number of national time series, including the supply of oxycontin (a proxy for consumption), prescriptions for oxycodone, some of the people who use painkillers recreationally, and health to meet the heroin poisoning all show a tendency to break down in August 2010, or immediately thereafter.”

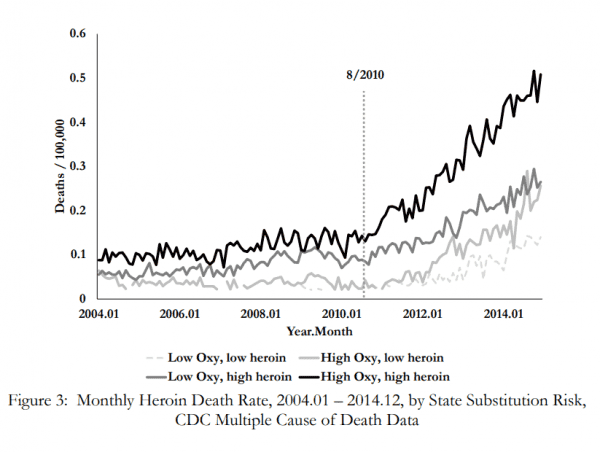

The document also looked at what the consequences were in different States, looking at it, based on the size of the States Oxycontin and heroin markets. He found that countries with a large Oxycontin and heroin markets saw the biggest increase in deaths from heroin. Conversely, States with small Oxycontin and heroin markets saw a small increase. So when heroin was widely available, people usually faster to switch from Oxycontin to illicit opioids.

The researchers looked at other possible explanations for the breaks in previous trends: if there is a sudden drop in the price of heroin that may have led to more heroin use, whether a new Drug monitoring database, may cut off access to Oxycontin and pushed people to heroin more than the reformulation, and if the crackdown on Florida clinics — in which unscrupulous were given opioid prescriptions — encouraged people to heroin more than the reformulation.

However, the researchers came to the conclusion that none of them can be the primary explanation of the results. They calculated, for example, that the acceleration Florida Pill mill explained at most 25 percent increase in deaths from heroin in the countries that were most exposed pills delivery Florida camp.

“We can’t completely deny that FL plays a role,” said Lieber. “But we can deny the fact that he played a major role.”

About fentanyl? This category of drugs has recently appeared on the black market where fentanyl and its analogues are often laced with other drugs or falsely sold as heroin. Because fentanyl is more potent than heroin, it creates an increased risk of overdose, which may explain the increased mortality. But fentanyl is considered to be soaring on the black market around 2013 — three years after the revision of Oxycontin, so long after the period of time that the study addressed.

There is one thing a lot of people who made the switch to heroin from Oxycontin, most likely, would have done so anyway. Keith Humphreys, a drug policy expert at Stanford University, told me that the “natural development” of addiction is that people will over time grow tolerant to opioids they are using and seek out more high. What could lead people to abandon Oxycontin and heroin, regardless of formulation. “Many of them turned out to be like heroin users,” said Humphries.

It is also only one study; future studies could produce different results. But now, the document suggests that the reformulation of Oxycontin may be, at least, has accelerated the growth of deaths from heroin overdose — perhaps enough to in the short term outweigh the lives saved by preventing more Oxycodone overdose.

This does not mean that making Oxycontin harder to abuse a bad idea

Humphries I have no doubt that some people really are switching to heroin due to the reformulation of Oxycontin. He said he personally knows people who have done it.

But he warned that this does not mean a revision of the Oxycontin was a bad idea.

Taking the argument to the extreme, someone could argue that we don’t have to do anything to get dangerous opioids from the market, because to do so might lead people to use instead of heroin, said Humphries. “Then we’ll just keep doing this forever? Continue to write 200 million prescriptions a year without any protection? … No. At some point you have to think about the future.”

To Humphrey, a pivotal moment in favor of a revision and other activities that have opioid painkillers harder to abuse is that they prevent more people from getting addicted to drugs. After all, if the problem was that the pain was so affordable that they made it easy for people to start on a path that ends abuse and heroin overdose, then the reverse is also true: making opioid painkillers are hard to get and abuse will stop people from going down the path of addiction. According to estimates Humphreys, it can prevent hundreds of thousands of overdose deaths more than a decade.

One way to think about this is what Humphrey describes as “stock” and “flow” opioid crisis.

On the one hand, you have current opioid users who are addicted to the people in this group need treatment or they will simply find other, potentially more dangerous opioids to use, if they lose access to pain or use of painkillers. On the other hand, you have to stop a new generation of people from the access and abuse of opioids — or they will get addicted to drugs and potentially overdose and die.

Activities for these different groups must not be in conflict. Consider the example given in the study: a person addicted to opioids by the abuse of Oxycontin pills, but when formula pills changed, he lost the ability to drug abuse, so he started to use heroin.

Part of this example shows that reformulation works as intended: the man was so burdened to change that he felt the need to go to heroin. For those who are still not addicted to heroin, this burden can stop them from ever abusing Oxycontin and, as a consequence, reduce the number of people who would otherwise become dependent on opioids.

For a person already in the stock of people dependent on opioids, however, it didn’t seem to do anything good, and actually may have pushed him to heroin.

But what if addiction treatment was made very accessible? So when this man came to the checkpoint on the abuse of opioids prescribed wording, he’d decided that it was time to enter treatment programs for addiction, not to heroin. Apply this thousands of times, and findings from the paper can be very different.

The reality of the us today is that treatment is not available enough for this to be realistic. According to the report of the 2016 General surgeon of the United States, only 10 percent of people with the disorder use substances to specialty treatment, largely because not enough adequate, affordable options to quickly get custody. In some States, for example, waiting periods for treatment can take weeks or even months.

This creates a situation where it is much easier to get high than to help you. So when people face obstacles in obtaining high because the drug is now they intended may not be as readily available or wrong, they are still able — and, therefore, likely to find another source than to treat.

Viewed through this prism, the rejection of the revision of the Oxycontin was not that it was originally a bad idea, considering he could have slowed the flow of potential opioid users — but that he is not paired with other measures that would help the existing stock of opioid users to avoid adverse effects in this population.

Lieber agreed that it was plausible. But he argued that the conclusions of the article still provide a lesson on the limitations and dangerous side effects — well-meaning intervention.

In this respect, Lieber stressed that the results apply only in the short term. It is possible that over time, Oxycontin reformulation will slow the flow of people become dependent on opioids to such an extent that it will allow the total supply of opioid users to reduce or even stop the growth and that will reduce the number of overdose deaths, than it could be.

Sourse: vox.com