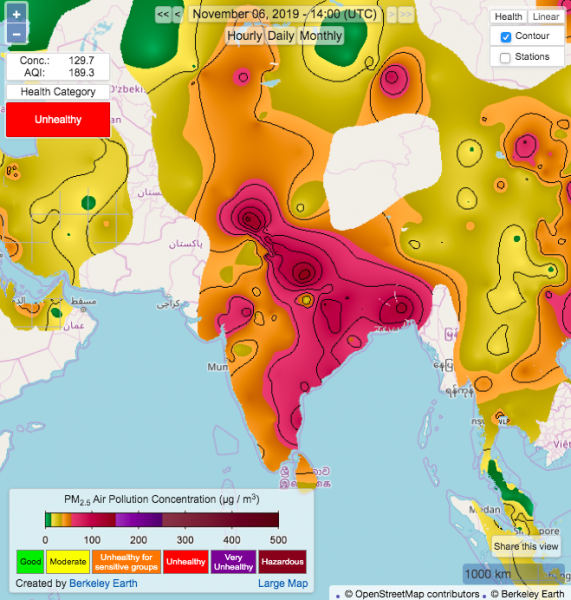

More than 20 million residents in Delhi’s metropolitan area are yet again facing some of the worst pollution on earth, with air quality degrading to dangerous levels this week as a mix of weather conditions, urban emissions, and rural smoke converge over India’s capital region.

Delhi’s Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal turned to Twitter to describe his city as a “gas chamber.”

The gray haze led to canceled flights, closed schools, and created a public health emergency. The government distributed 5 million face masks to schoolchildren.

On Monday, some air quality index monitors maxed out with ratings of 999 and pollution reached 50 times the level deemed safe by the World Health Organization. For Delhiites, breathing the air was like smoking 50 cigarettes in a day. The US Embassy in New Delhi maintains its own air quality monitor and reported Thursday that the air quality index improved to a rating of 255, merely “very unhealthy.”

This surge in air pollution in Delhi is an alarmingly regular occurrence, and it’s part of a dangerous pollution problem in India. The World Health Organization reported last year that 11 of the 12 cities in the world with the most pollution from PM2.5 — particles smaller than 2.5 microns in diameter that can cause dangerous heart troubles and breathing problems — were in India. The Lancet Commission on pollution and health found that in 2015, there were 9 million premature deaths stemming from air pollution around the world. India suffered the worst toll of any country, with more than 2.5 million of these deaths. Pollution has also shaved 3.2 years from the life expectancies of 660 million people in the country, according to one estimate.

While the very young, the elderly, and the infirm are most at risk, when pollution gets high enough, everyone can suffer. The effects can last for years, even from prenatal exposure. With a growing population throughout the country and more people moving to densely packed cities, the risk is worsening for Indians.

The dirty air is a consequence of both natural and human factors, and many emerging economies around the world are facing similar problems as societies urbanize and shift from agrarian to industrial. But air pollution is a problem with roots in politics, and in Delhi, much of the pollution can be traced to distinct policy decisions, including the unintended consequences of a water conservation law. The solution, then, lies not just in technology, but in better governance.

Why Delhi’s air pollution gets so bad this time of year

Joshua Apte, a professor of environmental engineering at the University of Texas Austin, explained that air quality is a function of pollution and dilution: how much is emitted and how much it spreads out. And right now in Delhi, there’s a lot of the former and not much of the latter.

In November, the air over Delhi gets cool, dry, and still. That ends up trapping much of the air over the city and limits its dispersal. The area is also landlocked and surrounding topology can act as a basin.

Then there are the pollution sources. Some of the biggest emitters are Delhi’s more than 10 million vehicles, like cars and trucks. Many of these vehicles run on two-stroke engines that produce more air pollution than four-stroke motors. Depending on the time of year, vehicles can contribute 40 to 80 percent of the region’s total pollution. Dust from the city’s construction boom is also a contributor to the city’s smog. Brick kilns that burn solid fuels are another factor. So is coal-fired power generation.

These sources contribute to Delhi’s year-round pollution. But there are several additional factors making air quality even worse now.

As temperatures drop, some of the poorer residents of the city are burning fires for cooking and heating, sending dust and ash into urban environs.

Some of the worst pollution this year also occurred during Diwali, the Hindu festival of lights, celebrated by lighting lamps, and often, by setting off fireworks. The celebration, which typically runs five days, began on October 27 this year.

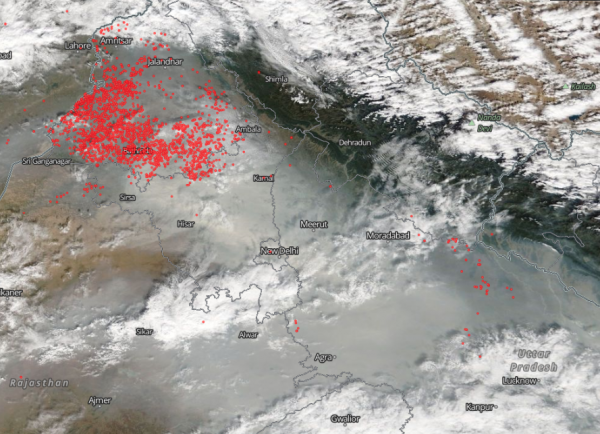

However, one of the largest sources of Delhi’s pollution right now isn’t coming from the city itself. Rather, farmers outside of the city this time of year burn crop stubble left over from the harvest to clear their fields and restore nutrients to the soil for their next planting. The smoke from these fires has wafted over the city in recent days.

Added together, it has become a recipe for choking, dirty air for millions of residents. “It’s like you’re pouring a whole lot of stuff off into a sink that’s plugged up,” Apte said. “It overflows with spectacular consequences.”

Delhi’s air wasn’t always so bad. A water conservation law helped fuel the rise in pollution.

“I’m actually a Delhiite, and I was born and raised in Delhi, and I never experienced this pollution,” said Aseem Prakash, founding director of the Center for Environmental Politics at the University of Washington. “The [severe] pollution has started really in 2010. The question is what happened in 2009?”

Prakash explained that the Punjab province west and upwind of Delhi is India’s breadbasket, and improvements in farming techniques in recent years in this region helped deliver a food surplus to the country.

However, these intensive farming techniques started to fuel a water shortage as farmers using cheap electricity overdrew from groundwater reserves. To combat this, the Punjab government in 2009 enacted the Punjab Preservation of Subsoil Water Act.

One of the key provisions of this law changed how farmers plant rice. Rice production typically takes place in two stages, where the crop is first cultivated in a nursery before being transplanted to a paddy. The water act prohibited nursery sowing before May 10 and transplanting before June 10. The delay allowed for seasonal monsoon rains to arrive and replenish aquifers.

By most accounts, the law worked. It slowed the decline of Punjab’s water table. But delaying planting means delaying the harvest. With a late October rice harvest, farmers now have barely a month to clear their fields for winter wheat, which is typically sown mid-November.

These farms are often run by small-scale farmers that can’t hire a large number of workers or afford the machinery needed to rapidly clear their fields of the leftovers from the last harvest. So they turned to the cheapest and quickest method to prepare for the next planting — burning crop stubble.

Of course, it’s not just rural pollution that’s choking Delhi. The urban sources of pollution — traffic, construction, cooking fires — have also increased as the region’s population has boomed by more than 7 million people in the past decade, leading to unchecked sprawl.

Together, these factors combined to cause a sudden devastating decline in air quality in Delhi in recent years.

Delhi officials are responding to the air pollution, but they are reluctant to take aggressive action

This year, officials in Delhi banned firecrackers ahead of Diwali, arresting 210 people and confiscating 3.7 metric tons of illicit incendiaries. But pops and explosions still rattled the city throughout the festival.

Brick kilns and factories have also been shut down this week. Delhi officials also implemented an odd-even traffic rationing scheme that takes about half of the cars off the road on a given day based on their license plate numbers. Roughly 200 teams of traffic police were deployed to enforce the rules. However, the scheme barely made a dent in the amount of pollution.

India’s Supreme Court on Monday also issued an injunction against crop burning. Yet fires have continued, showing that enforcement is a problem, and farmers are still in the early days of the crop stubble-burning season.

Added together, these stopgap measures have barely moved the needle. While air quality in Delhi has improved somewhat in recent days, analysts say it’s because of shifts in the weather — not policy.

“This is mainly due to the change in wind direction from north-westerly to south-easterly, which allowed Delhi’s air to slightly improve,” Kurinji Selvaraj, a research analyst at the Delhi-based Council on Energy, Environment and Water think tank told CBS News.

Getting more meaningful reductions in pollution means tackling all of the sources at the same time, which has proven to be an enormous hurdle. “Part of the challenge is that there’s a character of ‘Oh no, you first,’ ‘No, you first,’” Apte said. “No one sector wants to sign up for regulations that would lead to sharp cuts in their emissions when other sectors are not necessarily sharing equal portions of the blame.”

Part of the difficulty lies in the fact that every source of pollution is also a political constituency: farmers, landowners, property developers, construction firms, energy companies. In a democracy like India, they all have a seat at the loud, raucous table. There are also societal fault lines amid the pollution — many of the farmers in Punjab belong to the Sikh religious minority and politicians are worried that pressuring them could reopen old sectarian wounds.

Despite the growing alarm, air pollution scarcely came up during India’s last election cycle. And while Indian officials and courts are issuing edicts to stop sources of pollution, they are reluctant to enforce bans on burning, driving, fireworks, and industrial activity.

“People will be up in revolt, they’ll stop trains, there will be riots, and nobody wants to get into this hassle,” Prakash said. “It’s actually a very, very noisy and well-functioning democracy, and there are too many veto points.”

Air pollution can be solved. Some cities have made great progress.

Many cities around the world struggle with air pollution. London famously has been fighting dirty air since the 14th century and continues to suffer air quality problems today. Paris has also historically and recently suffered from dangerous smog.

In the United States, the San Francisco Bay Area and Los Angeles County regularly face air quality alerts when wildfires spark around them. And the country as a whole has experienced a spike in deaths stemming from air pollution due in part to weaker enforcement of environmental laws.

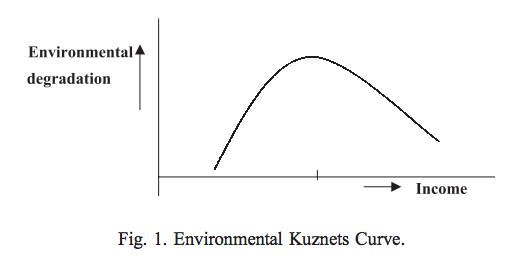

But the air quality problems in these cities are often transient, and many have made important progress in consistently improving air quality by enforcing environmental regulations, as well as deploying cleaner technology. The persistent dirty air over Delhi is a consequence of its current stage of economic development, similar to other megacities in developing countries.

This is the idea behind the Environmental Kuznets Curve. Named for economist Simon Kuznets, the hypothesis is that pollution in a country is low when it is impoverished. As incomes rise, the amount of pollution produced increases, but beyond a certain threshold of income, the pollution decreases again as pollution control technologies are deployed and governance structures are implemented. The highest pollution levels occur at the transition from an agrarian economy to an industrial economy, when the city or a country is getting the worst of both worlds.

But Delhi and cities like it are not doomed to follow this curve, Prakash said. Chinese cities like Beijing have managed to dramatically improve their air quality while still having moderate per capita incomes. A big reason that China’s air has cleared up, though, is that it has a more authoritarian government, so when Chinese officials give the order to shut down factories and limit traffic ahead of major events like the 2008 Beijing Olympics, it gets done. The government has since drastically reduced the amount of industrial and agricultural activity around the city.

“The beauty of China is that if they want something to be done, they can do it,” Prakash said. “Nothing stands between the decision and the implementation.”

That’s not the case with India, so reducing pollution takes more finesse. To clear the air over Delhi, Prakash said the government could issue subsidies and incentives for farmers to use less polluting land management tactics, helping them buy or rent machinery as well as paying them extra for their harvest if they pull it off without burning crop stubble.

India also has a law mandating that 2 percent of corporate profits go toward charity. Prakash said some of those funds could be earmarked to help farmers and reduce pollution.

Within Delhi, pollution reductions will have to come from switching to cleaner energy. “If one steps back and says, what is the largest contributor to pollution, the single largest contributor is fossil fuels,” Prakash said. It’s not just coal in power plants, but gasoline and diesel combustion in cars and trucks.

That means reducing urban air pollution by deploying vastly more renewable energy and clean transportation. At the recent United Nations Climate Action Summit, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi pledged that his country would more than double its renewable energy production, going from 175 gigawatts to 450 gigawatts by 2022. However, Modi did not commit to any reductions in fossil fuel use or greenhouse gas emissions.

It shows that despite all the known harms of air pollution, the pressure for economic development remains immense, and many public officials are willing to accept the tradeoffs.

While some of the solutions like wind and solar power are already being used, a region like Delhi demands deployment on a gargantuan scale in order to make a difference to its environment. That will take a huge amount of time, money, and foresight. The lessons learned in Delhi could also guide other growing metropolises facing air quality concerns like Karachi, Pakistan, and Lagos, Nigeria. “The problem can be solved,” Prakash said. “But what you need is political will and a bit of imagination.”

Sourse: vox.com