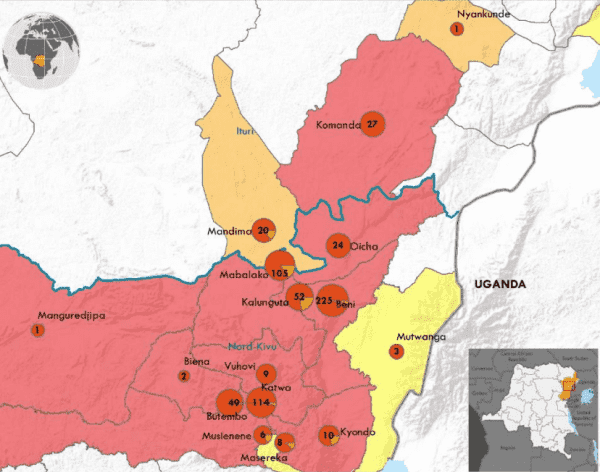

At least 680 people have been infected with the Ebola virus in the Democratic Republic of Congo. It’s the second-largest Ebola outbreak in history, with 414 deaths so far, and the first Ebola outbreak in an active war zone, DRC’s eastern North Kivu and Ituri provinces.

But it could get worse: Health officials this week are concerned that Ebola appears to be spreading in the direction of Goma, a major population center in DRC.

Just this week, DRC’s health ministry confirmed four cases of the deadly virus in Kayina, a town in North Kivu, where fighting among rebel and militia groups has repeatedly interrupted the painstaking work of health workers who are responding to the outbreak.

Kayina happens to be halfway between Butembo, currently one of the outbreak’s most worrisome hotspots, and Goma, where a million people live.

Join the Vox Video Lab

Go behind the scenes. Chat with creators. Support Vox video. Become a member of the Vox Video Lab on YouTube today. (Heads up: You might be asked to sign in to Google first.)

So far, the outbreak has not affected DRC’s biggest cities. But Ebola in Kayina “raises the alarm” for Ebola reaching Goma, Peter Salama, the head of the new Health Emergencies Program at the World Health Organization, told Vox on Friday.

Goma is a major transportation hub, with roads and highways that lead to Rwanda. “These are crossroad cities and market towns,” Salama added. People there are constantly on the move doing business, and also because of the insecurity in North Kivu. Ebola in Goma is a nightmare scenario WHO and DRC’s health ministry are scrambling to prevent.

Together, they’ve deployed a rapid response team, including a vaccination team, to Kayina. And if the virus moves on to Goma, Salama says Ebola responders are ready. They’ve already mobilized teams there, set up a lab, and prepared health centers where sick people can be cared for in isolation.

But as Ebola expert Laurie Garrett wrote in Foreign Policy this week, Ebola in Goma could also trigger a rare global public health emergency declaration by WHO, escalating the severity of an already dangerous outbreak.

An Ebola vaccine has been no match for DRC’s social and political chaos

When Ebola strikes, it’s like the worst and most humiliating flu you could imagine. People get the sweats, along with body aches and pains. Then they start vomiting and having uncontrollable diarrhea. They experience dehydration. These symptoms can appear anywhere between two and 21 days after exposure to the virus. Sometimes patients go into shock. In rare cases, they bleed.

The virus is spread through direct contact with the bodily fluids, like vomit, urine, or blood, of someone who is already sick and has symptoms. The sicker people get, and the closer to the death, the more contagious they become. (That’s why caring for the very ill and attending funerals are especially dangerous.)

Because we have no cure for Ebola, health workers use traditional public health measures: finding, treating, and isolating the sick, and breaking the chains of transmission so the virus stops spreading.

They mount vigorous public health awareness campaigns to remind people to wash their hands; that touching and kissing friends and neighbors is a potential health risk; and that burial practices need to be modified to minimize the risk of Ebola spreading at funerals.

They also employ a strategy called “contact tracing”: finding all the contacts of people who are sick, and following up with them for 21 days — the period during which Ebola incubates.

In this outbreak, there’s also an additional tool: an effective experimental vaccine. Since the outbreak was declared in August, more than 61,000 people have been vaccinated. But while the vaccine has tempered Ebola’s spread, it hasn’t overcome the social and political chaos in DRC, which has been called the world’s most neglected crisis.

“The brutality of the conflict is shocking,” Jan Egeland, head of the Norwegian Refugee Council, told the Thomson Reuters Foundation, “the national and international neglect outrageous.”

Presidential elections have “ratcheted up” the tension in an already tense situation

On December 30, after years of delays, voters went to the polls to elect a new president. In the days leading up to the election, tensions in North Kivu “ratcheted up,” Salama said. Protesters stormed Doctors Without Borders treatment centers in Beni, a recent outbreak hotspot, shutting them down for several days.

In January, the country’s electoral commission announced interim election results suggesting opposition leader Felix Tshisekedi had likely won the election. But leaked data and external analyses show there are irregularities with the voter count that point toward election fraud.

“All the outside observers — the African Union, the European Union, the Catholic Church — say the results of the election have been rigged,” and the people actually voted in Martin Fayalu for president, said Severine Autesserre, a political science professor at Barnard College, and author of the book The Trouble with the Congo. When the final results are announced in the coming days, more protests and riots are likely to follow.

But though the political instability isn’t making the Ebola response any easier, the war in Congo’s eastern provinces is a far bigger challenge. The 25-year-long conflict has displaced more than a million people, and made the already dangerous work of an Ebola response even more deadly, Autesserre said.

Between August and November, Beni had experienced more than 20 violent attacks, which put the outbreak response there on pause for days at a time. That meant cases had gone uncounted, and Ebola continued to spread.

But there’s also some more encouraging news, according to Salama: The outbreak of more than 200 people in Beni, a North Kivu town marred by decades of violence, has been brought under control.

“Many people would have been extremely skeptical that the outbreak in Beni could be controlled as quickly given force of infection we were seeing in November and December, and the fact that we’ve had nothing but volatility and insecurity since then,” Salama said. “But the fact that Beni has had only one confirmed case in two weeks is giving us a lot of hope and optimism.”

As of Friday, the the two biggest hotspots in the outbreak were Butembo, with 51 cases, and a neighboring city, Katwa, with 119 cases. But the outbreak is geographically dispersed. There are active Ebola cases in 12 of the country’s “health zones,” the districts around which the DRC’s health system is organized. Because of the insecurity and difficulty reaching people, only 30 to 40 percent are coming from known contact lists, Salama said. That means the virus might already be in places no one’s discovered yet.

Sourse: vox.com