Early on weekday mornings, I often find myself panting and sweating beside strangers in a dark room. Riding stationary bicycles with nightclub music blaring in my ears isn’t my idea of fun. But I turned to Flywheel’s spinning classes after the YMCA next to my office shut down, and now I’m hooked.

The draws for me are the ruthless efficiency of 45 minutes of grinding interval work and the fitness returns — running is a lot easier since I started spinning. The studio is also just a short walk from my house.

Yet I’ve been questioning my reliance on this luxury studio, and wondering what exclusive gyms like Flywheel and SoulCycle mean for America’s epidemic of physical inactivity.

These questions have forced me to reckon with two diverging trends in American exercise. On the one hand, new cycling, spinning, yoga, barre, and CrossFit facilities are popping up in cities all over the US, and now make up about 35 percent of the US exercise market, according to the International Health, Racquet & Sportsclub Association (IHRSA). The fitness industry overall generated $25.8 billion in revenue in 2015, up from $20.3 billion in 2010. Much of that growth is coming from these newer boutique facilities: membership at studios like Flywheel and SoulCycle exploded by 70 percent.

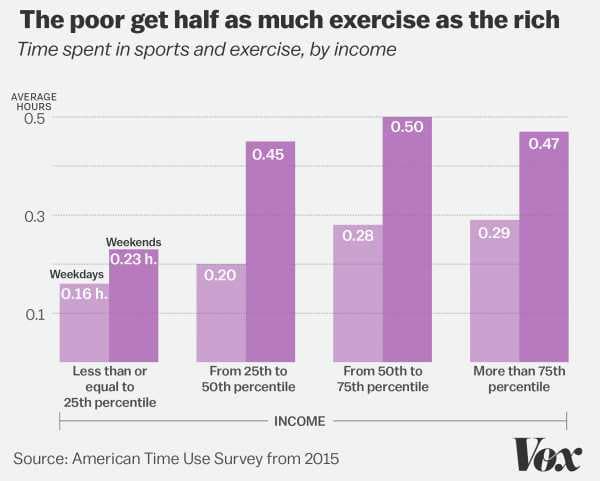

But here’s the rub: Higher-income Americans who can afford to join these places are not the group that most needs more exercise opportunities. According to the American Time Use Survey from 2015, the poorest quartile of the population gets about half the exercise of the wealthiest quartile:

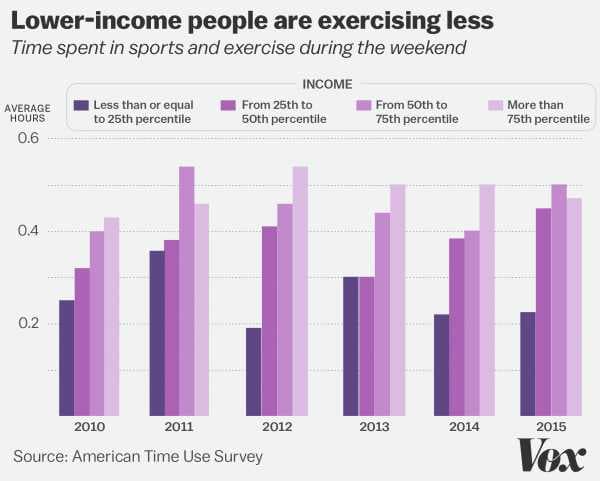

If you look at the trends over time, that gap is at best persistent, and at worst widening:

This entrenched exercise inequality — the rich getting fitter, the poor falling behind — also points to how exercise in America should be evolving: We need to make physical activity more accessible, not more expensive and exclusive.

“We privatize physical activity,” Elaine Waxman, a senior fellow at the Urban Institute, told me, “instead of investing in good public spaces where everyone can run safely or community centers with free yoga.”

Boutique fitness chains play into exercise inequality

It’s not difficult to understand the appeal of boutique gyms. A trip to Flywheel or CorePower Yoga can seem like a visit to the spa: There may be bowls piled with fruit. Gleaming white bathrooms with fluffy towels. $10 cold-press juices and racks filled with chic leggings and T-shirts.

These gyms have also figured out convenience for many people in metropolitan areas. From my home in central DC, I can walk less than 15 minutes in any direction and hit a boutique gym. The same is true in New York, Boston, and other major American cities.

These places appeal to our social desires, too. According to Meredith Poppler, a spokesperson for IHRSA, “[Boutique gyms and studios] cater to a very specific, specialized, and passionate segment who are very willing to pay more for being part of a ‘tribe.’” She added: “It’s the sense of belonging where everyone is like them versus a traditional club which caters to many different types of exercisers.” Acolytes like the specialization, she said, and enjoy working out alongside other dedicated spinning/yoga/Pilates/fill-in-the-blank fanatics like themselves.

But let’s be clear: A defining characteristic of the tribe using these workout spaces is affluence. It’s people with a good deal of disposable income — and an interest in fitness — who can pay to use these facilities. According to Vogue, they’ve even been relegated to the sphere of status symbol. “It’s become very much a brand in itself, the kind of sport and exercise you do,” Candice Fragis, the buying and merchandising director at Farfetch.com, told the magazine. Another spinning enthusiast said, “It’s like the only acceptable lifestyle brag.”

Many Americans don’t have access to safe and cheap workout spaces

This exercise gap is widening at a time when 45 percent of American youth don’t have parks, playground areas, community centers, or sidewalks and trails in their neighborhood, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (That average hides a lot of inequality and variation at the state and neighborhood level.) Less than forty percent of adults live within half a mile of a park.

There’s also been a decline in public investments in city parks during much of the 20th century, and some recent revivals in enthusiasm for green spaces in cities have been threatened by local government budget crises.

So many Americans don’t have access to basic spaces for physical activity — and the government is not investing enough in low-cost exercise options.

Public parks and YMCAs are spaces that theoretically welcome everyone. I have been a YMCA member in almost every city I’ve lived in, and I took yoga and swimming classes with people from every corner of society, age group, and fitness level.

The people in my Flywheel classes tend to skew young, well-heeled, fit, and white. I know I’ve certainly benefited from these boutique facilities, but I worry about the message they send of what fitness has to look like.

Make it easy to stay healthy and hard to get sick

There’s a pretty simple adage public health officials stick to: Make it easy for people to stay healthy, and make it hard for them to get sick. More specifically, as David Hemenway, a health policy professor at the Harvard School of Public Health, puts it, “Make it easy to get good food and hard to get lousy food, and make it easy to exercise.”

In America, we often do the opposite: “We make it harder and harder for people to get exercise and easier and easier to eat crummy food,” he said. Seven of the top 10 causes of death in America are chronic diseases — preventable conditions like diabetes and heart disease that slowly kill us because of the lifestyle choices we make.

How could we make exercise easier? We can remind people that simply walking more — while commuting, running errands, or even strolling around the mall — counts for a lot, health-wise. Exercise doesn’t need to be grueling, and it doesn’t have to cost anything.

We can make our communities more walkable or bikable. Imagine if more cities made their streets pedestrian-friendly and invested in spaces that everyone could access, such as community yoga studios, public parks, or even programs like Sunday San Francisco Streets or the Ciclovía in Bogota, Colombia, which involve closing down streets for walking and biking on the weekend. Researchers have found putting traffic-free cycling and walking routes in place increases physical activity levels for the people who live near them.

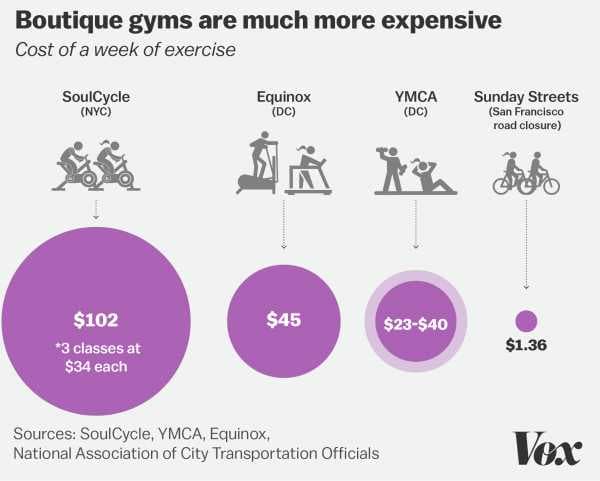

These public places also offer the most cost-effective forms of exercise, and they’re available to everybody, regardless of income. In this 2011 economic analysis, the researchers found Sunday San Francisco Streets cost only $1.35 per week. Meanwhile, they estimated, using pedestrian trails in Nebraska cost 81 cents, and the weekly cost of private fitness centers in cities like San Francisco runs about $20. Compare that with using a boutique spinning or Pilates studio two or three times per week, for which you can shell out more than $90.

To address this disparity, some boutique gyms are now trying to broaden their reach. SoulCycle offers free “community rides” each week and a two-month scholarship program for underserved adolescents, both efforts to “give the gift of fitness and movement to those who may not have access as well as connect with our community,” a company spokesperson told Vox.

But these efforts are not nearly far-reaching, sustainable, or accessible enough. It’s time to start asking what else we need to invest in to spread exercise opportunities more equally. As the rich get fitter, what are we doing for the rest of society?

Note: This piece was originally published in 2017.

Correction: An earlier version of this story had a subheading and sentence misstating the total number of Americans living near public workout spaces. The YMCA also contested the IHRSA data on their membership trends, so we cut that.

Sourse: vox.com