Mandy has now been in recovery from her opioid addiction for more than two months — and she’s ready to keep that going. But the 29-year-old in the Chicago area is now dealing with a big obstacle: her health insurer.

Mandy, who asked I use only her first name, said she struggled with addiction for six years. It started with back pain, which a doctor tried to treat with Vicodin.

“I had tried [opioids] in high school,” she said. “I had an older boyfriend, and I tried some of his wisdom teeth painkillers to get high off of. And I was like, ‘Whoa, this is awesome.’ When I got a Vicodin prescription for my back, I was like, ‘Oh, I remember these being really great.’”

Mandy took the drugs as prescribed at first. But every once in a while, she would sneak in an extra pill or two to help deal with a bad day. Then she started taking extras on good days, and, finally, at work.

“It got to the point where I started using them recreationally,” Mandy said. “But then I started using them to not get sick” — a typical experience for people addicted to opioids, who over time begin to use the drugs not to get high but to avert cravings and withdrawal.

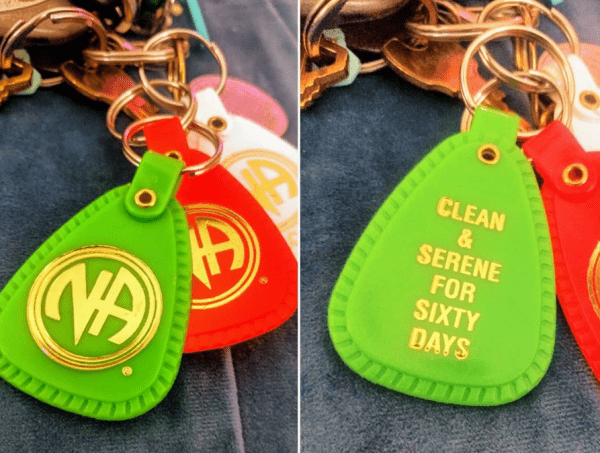

In March, Mandy decided she had enough. She got into an intensive outpatient addiction treatment program for eight weeks and was prescribed buprenorphine, a medication for opioid addiction that staves off withdrawal and cravings without producing the kind of high that, say, heroin or painkillers might. She’s remained on the medication as she’s transitioned to less intensive treatment.

There’s just one problem: Her insurer, Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Illinois, won’t pay for the buprenorphine. That’s left Mandy to foot the bill. Her latest bill — for a 28-day supply — was priced at $294 out of pocket, although she got it down to $222.69 with a discount. With the discount, similar bills throughout a full year would add up to nearly $2,900.

Related

We really do have a solution to the opioid epidemic — and one state is showing it works

The extra cost, Mandy said, comes on top of the other bills for day-to-day living, student loans, and health care expenses that she has to deal with, along with life’s other stresses. “I’m feeling all these old issues and all this shit, and then it’s just more bullshit,” she said. “I’m just trying to reenter society. … It’s really hard.”

It’s also a counterintuitive situation: “I never paid a dime for my opioids. Those were always covered,” Mandy said. “But I’m paying all this money for the treatment.”

The buprenorphine is central to her recovery. According to studies, anti-addiction medications like buprenorphine cut the mortality rate for opioid use disorder patients by half or more and keep people in treatment better than non-medication approaches. They are considered the gold standard of care for opioid addiction, with support from groups like the American Medical Association, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and the World Health Organization.

A Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Illinois spokesperson couldn’t comment directly on Mandy’s case due to privacy and legal concerns. But the spokesperson said the insurer “takes the opioid epidemic — and our role in addressing it — seriously,” has removed some barriers to paying for medication-based treatment, and aligns its standards for opioids and addiction treatment with federal guidelines.

Mandy’s situation, though, isn’t unusual. As I’ve traveled the country to report on the opioid epidemic, I have repeatedly heard complaints from patients and providers about insurance coverage. While the opioid crisis continues to kill tens of thousands of people each year, a common hurdle to preventing these deaths seems to be insurers refusing to pay for the type of treatment that we know has the best chance of working.

A few days of delay can be deadly

There’s no good research on how common Mandy’s experience is. Some limited evidence shows that levels of coverage and relevant barriers vary from state to state and health plan to health plan, but we don’t have a good picture of just how insurance coverage of opioid addiction medications looks nationwide.

Anecdotally, though, it’s an issue that’s come up repeatedly in my reporting.

Mandy’s doctor, Dennis Brightwell, said that this problem mostly arises in his practice with patients who are on private insurance. While state law requires Medicaid to cover federally approved medications for opioid addiction, the same does not apply to private insurers. That allows not just rejections, like in Mandy’s case, but also issues with what’s called “prior authorization” — essentially, an extra hurdle that requires the prescriber to get prior approval from an insurer before the insurer pays for it. (Mandy’s insurer, Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Illinois, said it previously removed a prior authorization requirement for medication-based treatment.)

“If you send a commercial patient to the pharmacy, you don’t know until they get there how it’s going to go,” Brightwell said. “Sometimes it’s not such a problem. Sometimes it’s a prior authorization that is pretty straightforward. Sometimes it’s very difficult to get them to approve it. And there’s not an easy way to find out upfront what medications they approve.”

In Kansas, Sara Ballare-Jones, a social work case manager at the University of Kansas Health System, said her clinic constantly struggles with prior authorization problems. These can cause delays as long as weeks, although typically not more than three days, for a patient trying to get a prescription filled. Ballare-Jones said this happens with both Medicaid and private insurance, drawing a contrast to Brightwell’s experience in Illinois.

In New York, Aaron Fox, a doctor and researcher, said that his experience hasn’t been quite as bad as that of providers in other states. In some of the worst cases, he’s seen patients struggle to get medications for hours or days — but it’s typically more of “a hassle” that, more than directly harming patients, can “break down the wary physician and dissuade people from prescribing.”

Still, even a few hours’ delay in filling out a prescription can be risky. The initial stages of someone with a drug addiction seeking help can be extremely sensitive. The patient is dealing with finally confronting the fact that they have a problem — an admission that doesn’t come easily. They also are dealing with real medical issues: not just withdrawal and cravings, but perhaps additional physical and mental health issues also linked to their addiction.

It’s a highly stressful situation that might, paradoxically, make drugs even more tempting. And any relapse can end with an overdose. “The risk of relapse is incredibly high,” Ballare-Jones told me.

The insurance problems only add to the pile.

“It makes me want to go out and use [drugs],” Mandy said. “It’s way easier to get opiates or heroin. … It’s so much easier than dealing with this bullshit.”

Mandy’s cost concerns may eventually be addressed through appeals to her insurer, but the process is confusing. The initial rejection letter from Mandy’s health plan, for example, had no significant details explaining why her specific prescription was rejected.

To get her insurance to pay for her buprenorphine, Mandy and her doctor now have to figure out what, exactly, the problem is and then deal with an appeals process that could take months. Mandy said that her initial appeal was already rejected, but she’s now going through another appeal that could take as long as 90 days.

Beyond rejections and prior authorization requirements, some insurers also set dose and duration limits. A 2015 study published in the Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, for example, found that 11 state programs at the time, based on 2011 to 2013 data, set one- to three-year lifetime treatment limits. Given that addiction is a chronic condition and treatment can be required for life, there is no empirical or medical basis for these kinds of limitations.

The insurance barriers are one reason addiction treatment remains difficult to access in America. According to a 2016 report by the surgeon general, only 10 percent of people in the US with a drug use disorder get specialty treatment, which the report attributed to a lack of access to care.

Much of that is related to a lack of supply of evidence-based treatment providers; the White House’s opioid commission, for one, found that 85 percent of US counties have no specialty opioid treatment programs that provide medications for opioid addiction. But Mandy’s case shows that even when providers are available, there can be additional hurdles that hinder access to care.

Policy can help address these problems, but enforcement is tricky

When I described Mandy’s circumstances, Richard Frank, a health economist at Harvard Medical School, said that a situation like hers may already be illegal under federal parity laws going back to President George W. Bush’s administration. These laws require that if an insurance company covers mental health care, it should do so at the same level as it does for physical health care.

Historically, Frank said, insurers have been reluctant to cover addiction treatment, because they saw patients with addictions as too expensive, and they saw it as a non-medical issue — so outside their purview. “These guys don’t want to change what they’re doing, because it’s going to cost them money,” Frank told me.

Tami Mark, a health economist at RTI International, said stigma toward addiction plays a role as well. “Buprenorphine and methadone are incredibly effective medications,” Mark said. “If you had any other drug with their kind of effect size, it would be immediately covered. … So I really do think it’s a stigma issue.”

Parity laws attempt to address this. Citing the prior authorization process, Frank explained, “The test is as follows: Do they apply the same rules at arriving at prior authorization for behavioral health drugs as they do for other drugs?”

To give an example of how this works, imagine an insurance plan that will pay for evidence-based heart disease medications, with no extra costs or barriers. Parity laws require that the insurer, if it claims to cover mental health and addiction treatment, would have to cover an evidence-based medication for addiction at a similar level.

There are some complicating factors. For example, buprenorphine is an opioid that can be misused. An insurer could decide, even under parity laws, to impose additional barriers on buprenorphine to prevent the risk of misuse and diversion to the black market.

Enforcement can also get tricky. Frank said that lawmakers and regulators can ensure that insurers are following the broad strokes of the law when they set up the general structure of what they cover — what kinds of treatments are in theory paid for, medication formularies, annual and lifetime limits, and so on.

Where it gets complicated is when dealing with more nuanced, on-the-ground issues. For example, maybe an insurer will say it’ll cover all drugs as long as they’re deemed medically necessary. But what is medically necessary? Who defines that? And how?

“When you do that on a case-by-case level, it’s very hard to enforce,” Frank said. “You have to do a lot of investigation. And, you know, there are judgment calls here.”

There are prominent calls for this to change. The White House’s opioid commission, for one, dedicated a section of its final report to better enforcement of parity laws, asking that the Department of Labor get “real authority to regulate the health insurance industry” and that insurers that violate parity laws “be held responsible.”

Beyond parity requirements, states can enact laws and regulations that force insurers to cover certain medications without prior authorization or other barriers. That’s what Illinois has done with Medicaid and buprenorphine. And according to Brightwell, it’s improved the situation on the ground when dealing with Medicaid plans, particularly compared to private insurance plans that don’t face the same rules.

In general, these measures are about getting insurers on board with a rapidly changing mainstream view of what addiction is. As America spent decades dealing with addiction more as a criminal justice issue than as a public health concern, it’s been easy for insurers to punt on paying for this kind of care. But as the opioid epidemic forces the country to rethink how it looks at addiction — by putting it into more of a public health framework — that may be starting to shift.

Until then, people like Mandy fear getting left behind.

“I have friends who died from heroin,” she said. “I know people in treatment who relapsed multiple times just in the eight weeks I was there. I mean, it’s rough. This is not an easy thing to kick. And that’s why I need the buprenorphine.”

Sourse: vox.com