There’s a mass of seaweed in the Atlantic Ocean that last year, at its peak, was so large it stretched all the way from the Gulf of Mexico to West Africa. It’s the biggest bloom of seaweed ever recorded, according to a new paper published in Science. And it’s likely another example of how human activity is radically changing the surface of the planet.

The giant seaweed mass is both expansive and heavy, weighing a whopping 20 million tons last year. It’s comprised of a macroalgae species called sargassum, a brown seaweed that forms little bubbles that look a bit like grapes. Large volumes of it washing ashore can be a pain for beach tourism. See:

Those bubbles allow the seaweed to float on the surface, which in turn lets scientists track its distribution over time. The brown hue of the seaweed on the surface of the water can be seen by satellites.

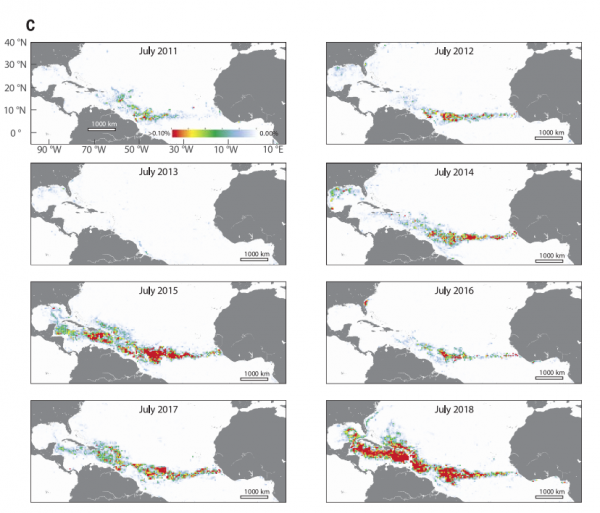

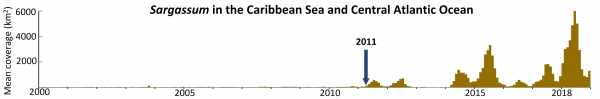

Satellite images have revealed that over the past 20 years, the mass of sargassum on the surface of the Atlantic has exploded dramatically. The following chart shows the density of sargassum in the Atlantic every July (the month when sargassum blooms peak) from 2011 on. You can see in July 2018, it was the densest, stretching clear across the ocean.

The study authors call it the great Atlantic Sargassum belt, and suspect it’s likely the result of more nutrients, mainly nitrogen and phosphorus, running off the West Africa coast into the ocean in the winter. The belt is also being fed by the same nutrients, from fertilizer runoff and deforestation, running off into the Amazon River and into the ocean in the summer.

The sargassum responds to those extra nutrients like many plants would: It eats them, and grows. The bloom sizes also continue to grow every year because there are sargassum seeds left over from the previous summer.

There isn’t data available yet on the extent of the mass this month, but many beaches in Mexico are currently blanketed in the stuff, possibly signaling another bad year for sargassum growth. (It costs Mexico’s beaches millions a year to deal with the increasing growth of the seaweed.)

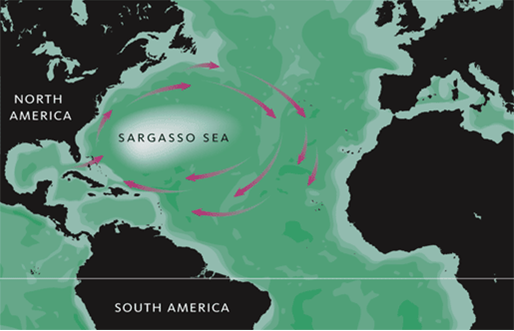

The seaweed, historically, has been mostly confined to the Gulf of Mexico and a region of the Atlantic called, well, the Sargasso Sea. It’s a region encircled by ocean currents which keeps its ecosystem a bit separated from the rest of the Atlantic.

And the sargassum is an important component of that ecosystem, as NOAA notes:

But it started to spread around 2011, especially in the central Atlantic, with the uptick of nitrogen and phosphorus flowing into the ocean from South America and West Africa.

The new excess of sargassum is not a good thing. It floats onshore, rots, and smells like sulfur, making it a pain for beach tourism in the Caribbean and in Mexico. When it dies in the ocean, it can sink, and possibly harm corals. Dense groves of sargassum can also trap and harm sea turtles.

“The ocean’s chemistry must have changed in order for the blooms to get so out of hand,” Chuanmin Hu, a University of South Florida marine scientist who led the Science study, said in a press statement.

In a lot of ways, this story isn’t unique. In many, many waterways — including lakes used for drinking water — fertilizer runoff induces incredibly large blooms of (often toxic) algae. Last year, a “Red Tide” bloom of algae killed at least a hundred manatees, a dozen dolphins, thousands of fish, and 300 sea turtles off the coast of Florida. It was all the result of an algae called Karenia brevis growing in mass and releasing a neurotoxin.

In 2015, a toxic bloom of blue-green algae in Lake Erie left half a million people without drinking water. In the Gulf of Mexico, runoff from the Mississippi River often leaves “dead zones” — where, ironically, a boom in algae growth sucks up all the oxygen in the water and everything, including the algae, have to flee or die.

The bottom line: More and more of our refuse is getting into the ocean, and other waterways. And it’s leaving a huge mark.

Sourse: vox.com