After Jenna Angst gave birth to her second child, she noticed that her midsection didn’t look right. “I was frustrated that my stomach looked so pudgy, even after I got back to my normal weight,” Angst, 37, says. So she asked her OB-GYN in Atlanta to take a look. The doctor brushed her off, telling her it was purely aesthetic.

But Angst wondered if it might be something she’d heard about in a yoga class once that went by the name of “mom pooch,” “mummy tummy,” or “baby belly.” So she went to doctors, specialists, and physical therapists in search of an answer. Finally, one told her that, yes, she had diastasis recti, a condition where the abdominal muscles separate so much that the stomach protrudes.

“I found it appalling that I had to go on such a journey to get answers — talking to friends, to my OB, to a [physical therapist] and four plastic surgeons,” said Angst, who eventually got treated for the condition. “The information is not readily available. It wasn’t until well after my son’s first birthday that I had some answers.”

Angst’s struggle to understand this postpartum condition is not unusual. Though research suggests that at least 60 percent of women have DR six weeks after birth and 30 percent of women have it a year after birth, most women have never heard of the term.

As with many other postpartum complications that affect women, there is little good research on the condition. Women aren’t routinely screened for DR at the one standard postpartum visit that occurs around six weeks after birth. And if they do get a diagnosis, they are often told that core work — for instance, tons of crunches — will tone the tummy and thus, close the gap.

But core work done improperly or alone won’t necessarily fix the problem. In fact, it can even make things worse. And over the long term, DR can compromise the stability and function of the core, and is linked to a host of other problems that can crop up even years after childbirth.

Given that so many women are forced to learn about DR on their own, here is a guide for how to try to prevent it and address it from those who treat it.

Diastasis, defined

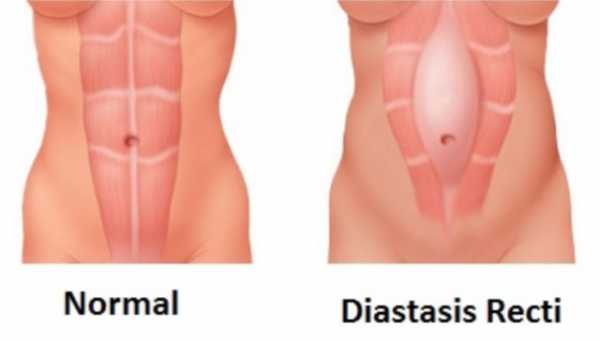

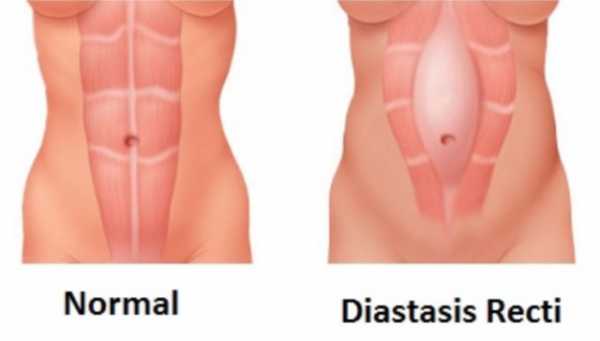

Diastasis recti is caused by the overstretching of the linea alba, the tissue or fascia at the center of the rectus abdominis muscles, the “six-pack” muscles to the right and left of the bellybutton.

The normal width of the linea alba between the rectus abdominis allows you to bend, twist, and carry a fetus. “There is a natural opening there whether you’ve had a baby or not,” says Brandi Kirk, an Illinois-based pelvic health specialist and educator at the Barral Institute. “It’s where the umbilical cord was.”

But too much pressure can stretch it out. Doctors diagnose diastasis recti when the distance between the two sides of the rectus abdominis muscle gets to be two centimeters or more.

DR can affect anyone — women, men, and children. “Coughing, laughing, pooping, breathing, birthing, and moving (i.e., your posture and exercise habits) are all things that can change the amount of pressure in your abdomen” and can, over time, cause DR, writes Katy Bowman, a biomechanist, in her book Diastasis Recti: The Whole Body Solution to Abdominal Weakness and Separation.

It’s most common in pregnant and postpartum women because of the load a growing fetus places on the linea alba, which Bowman likens to a shirt seam. The linea alba connects muscles the way the seam connects fabric, but it’s also the shirt’s weakest part, prone to splitting when stretched too much. “Abdominal separation is not about fitness; it’s about forces,” says Bowman.

Postpartum DR is underreported and undertreated

Clinicians who treat DR say they see it most in women who carry large babies or twins, have given birth multiple times, are petite or short-torsoed, or have tight abdominal muscles prior to pregnancy. Other women at risk include those with a history of surgery, C-section, constipation, or weak connective tissues.

Alicia Willoughby, a pelvic health physical therapist who has treated more than 100 women with DR, believes it’s more common than doctors acknowledge. She says the data we do have likely doesn’t capture the full extent of the problem, “because it is underreported, and many women are never screened for one.” Most often, women learn about it in an exercise class, or they self-diagnose after reading about it online.

DR can affect women even years after pregnancy and childbirth, and can lead to all kinds of problems and pain — like pelvic organ prolapse (when organs drop into the vagina), urinary and fecal incontinence, loss of stability, breathing and digestive problems, pelvic girdle pain, back pain, and pain or reduced sensation during sex.

Michele McGurk is a women’s health physical therapist specializing in abdominal and pelvic dysfunction in Brooklyn, New York. She says that a separation two and a half finger widths or wider is where she begins to see dysfunction in other areas of the body. Some 66 percent of women with DR also presented at least one form of pelvic floor dysfunction, like incontinence or prolapse, in a survey of urogynecology patients.

The most accurate way to diagnose DR is with ultrasound imaging, but pelvic health physical therapists and urogynecologists — the specialists who see the condition most — usually diagnose it manually. They say the best time to be evaluated is at least six weeks after birth, once tissue has healed and the uterus has shrunk to its pre-pregnancy size. During a screening, a woman lies supine, exhales, then lifts into an abdominal curl. Then a clinician measures the gap above, below, and at the navel with her fingers.

Why some people object to calling it “mummy tummy”

DR can give the belly a soft, protruding appearance. It can push the bellybutton out, or look like a visible gulch at the midsection when a woman bends or does an abdominal curl.

Courtney Wyckoff, the founder of the Momma Strong workout program, suffered from a large DR and related pain after pregnancy. But she argues the focus around DR should be on mobility and function, not aesthetics. For instance, can a woman bend and touch her toes? Can she wake up without pain? Is she peeing herself?

But most of the DR advice out there is on how to flatten the tummy and “bounce back” after pregnancy rather than how to strengthen the function of the core, pelvis, muscles, and organs. A recent NPR story, “Flattening the Mummy Tummy With One Exercise 10 Minutes a Day,” elicited a huge response, both positive and negative. Some women felt it reinforced the problematic cultural standard that women should have flat tummies. A follow-up NPR story addressed some of the comments and recommended additional exercises.

Still, few studies have evaluated DR treatment thoroughly enough for there to be definitive clinical guidelines about how to treat it.

Exercise may help, but you can’t talk about repairing DR without talking about the pelvic floor

The clinicians I interviewed who have diagnosed and treated hundreds of DR cases collectively agree that it can be treated. But they stress that the abdominals are only part of the equation. McGurk coaches women to reconnect to their pelvic floor and their transverse abdominis muscles, which can essentially turn off during pregnancy and childbirth.

“The transverse abdominis and the pelvic floor are best friends that need and can’t work without each other.”

Abdominal exercise, coaching, and visualization that incorporates the pelvic floor and proper breathing techniques (inhaling when relaxing, exhaling when contracting) can reestablish the connection between the muscles and the brain and strengthen not only the abdominals but also the pelvic floor, she says.

“Stabilizing diastasis during pregnancy and postpartum is all about reconnecting the brain with the deep abdominal layer called the transverse abdominis,” says Willoughby. “The transverse abdominis and the pelvic floor are best friends that need and can’t work without each other.”

A 2014 review of eight studies evaluating what impact exercise has on preventing or healing diastasis was inconclusive. Recent studies have tested two specific exercises on DR — abdominal crunches and an exercise called “drawing in.”

Drawing in involves inhaling to fill the belly with air, then exhaling and moving the belly back toward the spine. (Willoughby says the key is to inhale as you relax muscles and then engage as you exhale.) But in the study, the subjects were only measured doing the exercises in a lab, not over a period of time.

Wyckoff teaches a technique called bracing that involves contracting the abdominal muscles in concert with lifting the pelvic floor “like a claw crane.” If you’re not sure if you’re doing it right, see a trained professional who can test and feel if the proper muscles are engaging during the exercises.

New DR research is looking at techniques that go beyond exercise

Brandi Kirk has treated DR for a decade. She and others trained in visceral manipulation, a physical therapy technique developed by French osteopath Jean-Pierre Barral, have applied it to the small intestine and seen DR patients improve function and narrow their gaps. Kirk presented the findings of a very small case study of the technique at the American Physical Therapy Association conference, and will expand her study next year.

A controlled trial from Cairo University in Egypt recently discovered that women who used neuromuscular electrical stimulation, which uses electrical current to get muscles to contract, on their abdominal muscles in addition to exercise saw more DR improvement than women who did exercise alone.

Exercises can only go so far if other daily movements don’t support the work, according to Bowman. “It’s not only about how or how much you exercise — there’s a whole bunch of non-exercise things, like how you breathe, how you hold your body (read: suck in your stomach), and even how you dress, that can place unnatural loads on your linea alba,” she explains in her book.

Some doctors opt to repair DR with laparoscopic surgery or abdominoplasty, often accompanied by liposuction. This can be a viable option for severe cases of diastasis and abdominal hernia. But research on the DR-repairing operations has found that surgical correction carries risks and is “largely cosmetic.”

The pelvic health therapists I spoke to stress that surgical repair won’t teach the muscles to function properly, and that women who undergo surgery should seek out rehabilitative physical therapy afterward. These surgeries are also costly and aren’t usually covered by insurance.

DR is technically healed once it measures two finger widths or less. But the pelvic health physical therapists are concerned with more than measurements — they want to see that the tissues support the abdomen, and that woman can function without pain elsewhere in the body.

Crunches done wrong can make DR worse

Some health care providers and fitness instructors believe that a flabby postpartum belly can be flattened simply with abdominal exercise, such as crunches — which many people with DR end up doing wrong and with too much force.

“A lot of women out there taking Pilates and yoga classes are not engaging the correct muscles,” McGurk says. “One of my primary concerns is to get the proper muscles firing. Are you feeling the two sides of the TA glide together? For the majority of women it’s not happening, or it’s asymmetrical.”

Particularly, crunches done wrong can encourage diastasis, or worsen it. PTs tell pregnant and postpartum women to avoid any sit-up-like motion or abdominal exercise in which the head or feet leave the floor. Upper body twisting, spinal extension (like in a bridge pose), and bearing down during a bowel movement can increase pressure on the linea alba and encourage muscle separation.

Anything that forces the belly to bulge can pose a risk for further separation or even abdominal hernia, when an organ protrudes through a gap. Willoughby says that a DR is not healed “if there is doming or bulging along the middle of the abdominals when a load is placed on the body, such as lifting a child.” Wyckoff recommends that women with separation lift themselves up from a supine position by rolling to one side and using their arm to push up, rather than curling straight up.

DR can be prevented during pregnancy

A common occurrence clinicians see leading to DR is when pregnant women ignore their core altogether. “During pregnancy the core muscles take a little vacation,” Willoughby explains. “We need them to work and stay functional. Keep those muscles active through exercise. That may help prevent DR or speed recovery.”

Bowman says OBGYNs often tell pregnant women to avoid abdominal exercise altogether because they, like many, are only thinking of crunches. Instead, they can do strengthening exercises like drawing in or bracing that engage abdominal muscles and pelvic floor muscles. (See the Momma Strong for more details on the exercises.)

Pregnancy can be one of the best times to work on diastasis prevention. “Your body, your baby’s body, your pregnancy, and your delivery could benefit greatly from working to restore functional, biologically necessary core strength while you’re pregnant,” Bowman writes.

The other good news is that it’s never too late to work to repair a diastasis, according to clinicians. And Wyckoff stresses that if unhappiness with a DR’s appearance is why women decide to address their stability and function issues, that’s fine.

“It’s okay to not want a pooch,” she says. “I think that’s a primal, normal way in. Once you feel that, the question becomes how am I going to support this, and what else does it mean for my body? It’s going to take a lot for us to start focusing on function.”

Allison Yarrow is a journalist, a TED resident, and author of the forthcoming 90s Bitch: Women, Media, and The Failed Promise of Gender Equality. Find her on Twitter @aliyarrow.

Sourse: vox.com