You may have heard that last year’s allergy season was the worst ever. So was the year before. Allergy season has become so predictably terrible that late-night comedians have taken to venting about warnings of the “pollen tsunami” ad “pollen vortex” or a “perfect storm for allergies.”

But it turns out there is truth behind the bombast. Pollen allergy seasons truly are getting worse, and global warming is a major factor.

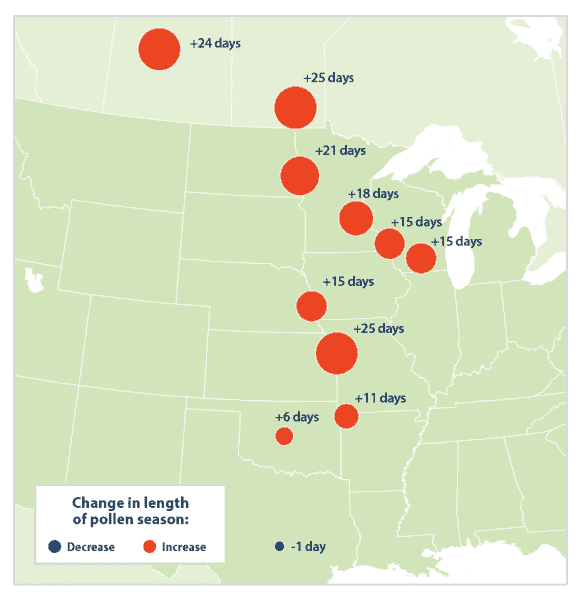

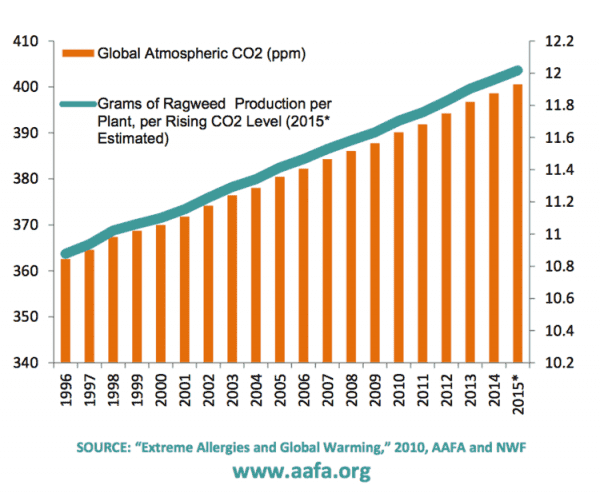

For one, there’s evidence that the number of people with allergies is increasing, and with changes in average temperatures, pollen seasons are also getting longer, as you can see here in this map of the growth in ragweed’s pollen season:

People in areas farther north, like Alaska, where the climate is changing faster, typically experienced fewer allergies in previous years but are now becoming increasingly vulnerable. Taken together, seasonal allergies present one of the most robust examples of how global warming is increasing risks to health.

“It’s very strong. In fact, I think there’s irrefutable data,” said Jeffrey Demain, director of the Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology Center of Alaska. “It’s become the model of health impacts of climate change.”

And since so many are afflicted — some estimates say up to 50 million Americans have nasal allergies — scientists and health officials are now trying to tease out the climate factors driving these risks in the hopes of bringing some relief in the wake of growing pollen avalanches.

Squinting through the springtime haze, here’s what scientists have figured out so far about the relationship between climate change and seasonal allergies.

Pollen is becoming impossible to avoid

Allergies occur when the body’s internal radar system locks on to the wrong target, causing the immune system to overreact to an otherwise harmless substance.

This can cause mild annoyances like hives or itchy eyes, or life-threatening issues like anaphylaxis, where blood pressure plummets and airways start swelling shut.

About 8 percent of US adults suffer from hay fever, also known as allergic rhinitis, brought on by pollen allergies. Most cases can be treated with antihistamines, but they cost the United States between $3.4 billion and $11.2 billion each year just in direct medical expenses, with a substantially higher toll from lost productivity. Complications like asthma attacks induced by pollen have also proven fatal in some instances and lead to more than 20,000 emergency room visits each year in the US.

Pollen is a fine powder produced as part of the sexual reproductive cycle of many varieties of plants, including elm trees, ryegrass, and ragweed.

It’s released in response to environmental signals like temperature, precipitation, and sunlight. Grains of pollen range in size from 9 microns to 200 microns, so some types of pollen can travel deep into the lungs and cause irritation, even for people who don’t have allergies. High concentrations of pollen in the air trigger allergic reactions and can spread for miles, even indoors if structures are not sealed.

There are three big peaks in pollen production throughout the year. Trees like oak, ash, birch, and maple see pollen surges in the spring. Pollen from timothy grass, bluegrass, and orchard grass peaks over the summer, and ragweed pollen spikes in the fall. For people who are sensitive to multiple varieties of pollen, it means there will be less relief during warmer weather as these seasons overlap.

We’re already seeing a strong climate signal in pollen-spewing plants

In general, pollen is emerging earlier in the year and the season is stretching out longer and longer, especially pollen from ragweed.

Ragweed is handy for studying the impacts of climate on pollen and allergies because it’s an annual plant, unlike trees or perennials. This allows scientists to separate out how variables like winter temperatures and rainfall in the preceding season influence ragweed pollen.

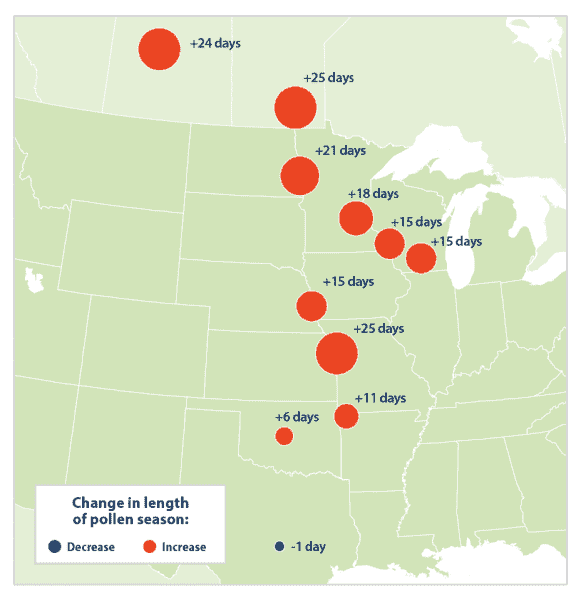

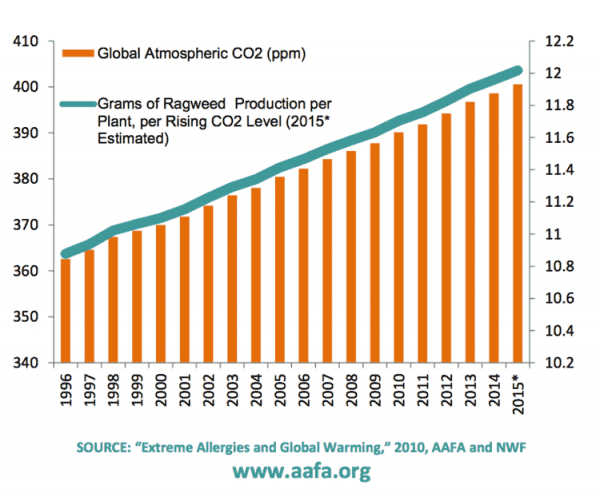

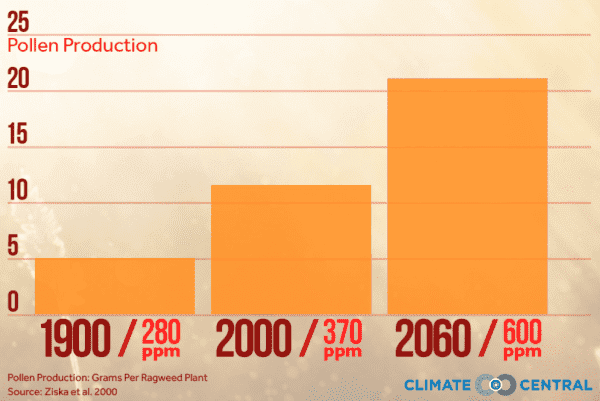

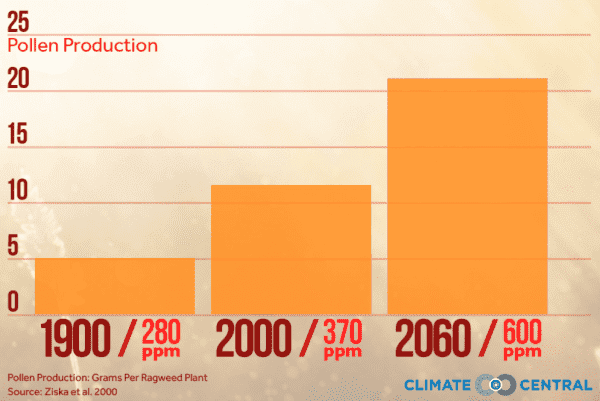

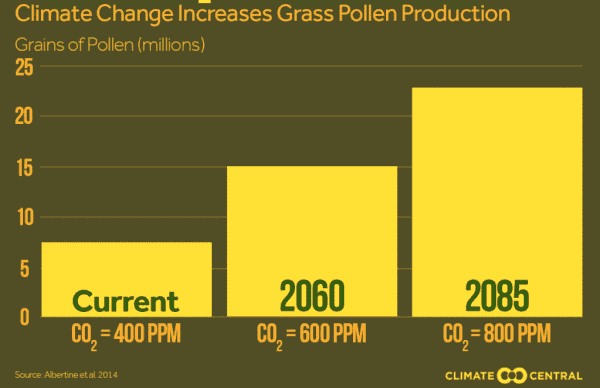

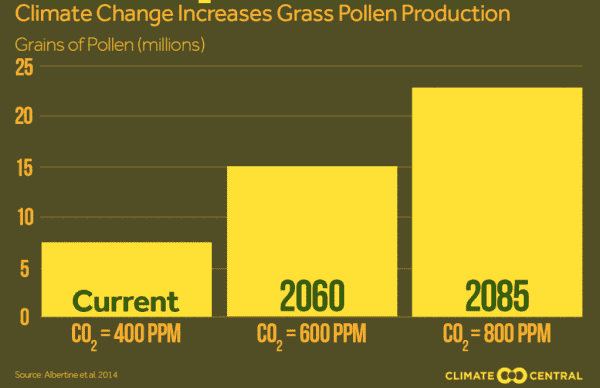

Lewis Ziska, a research plant physiologist at the US Department of Agriculture, told me that the change in carbon dioxide concentrations from a preindustrial level of 280 parts per million to today’s concentrations of more than 400 ppm has led to a corresponding doubling in pollen production per plant of ragweed.

How does this happen? If you’ve looked at a bag or bottle of plant fertilizer, you may have noticed three numbers that represent the ratio of phosphorus, nitrogen, and potassium inside. Different ratios encourage different aspects of a plant’s growth, like flowering or making seeds. Carbon dioxide is also an important nutrient for plants, though it’s not included in fertilizer (because it’s a gas). It turns out that higher carbon dioxide concentrations encourage plants to produce more pollen.

For ragweed, you can see a direct pollen response to increases in carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere:

More pollen usually means more seeds, which means more ragweed in the next season. And warmer average temperatures mean that spring starts earlier and winter arrives later, giving pollen producers more time to spew their sneeze-inducing particles.

We can see the effects of CO2 on smaller scales as well. Researchers have found that grasses and ragweed plants increase their pollen production in response to localized surges in carbon dioxide, like from the exhaust of cars along a highway.

However, for other allergen sources like trees, the groundwork for severe pollen year can be laid more than a year before the current season.

“What happens is if the tree during the previous year has had a ‘good season,’ it tends to load up on carbs so that in the spring, it has a lot of carbs to put out for flower production,” Ziska said. “When that happens, you can get a large bloom, and the consequences of that are inherent in the amount of pollen that’s being produced.”

The far north is getting hit the hardest

Alaska is warming so fast that computer models have had a hard time believing the results. That’s having huge consequences for allergy sufferers in the state, and not just from pollen.

Demain from the Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology Center of Alaska explained that rising temperatures are melting permafrost beneath Alaskan towns, causing moisture to seep into homes. This dampness then allows mold to grow, causing more people to seek treatment for mold allergies.

Stinging insects are also a mounting concern. Warmer winters mean that more yellow jackets and wasps are surviving the cold months, increasing the likelihood of Alaskans getting stung. In 2006, Anchorage saw a spike in the numbers of these insects and suffered its first two deaths ever due to insect sting allergies.

“It was so bad they were canceling community outdoor events,” Demain said.

Looking at patterns of people seeking medical treatment from insect stings, Demain found that the increases grew starker going northward in Alaska, with the northernmost part of the state experiencing a 626 percent increase in insect bites and stings between 2004 and 2006 compared to the period between 1999 and 2001.

Nonetheless, pollen remains a huge concern in Alaska as well, though the main source is birch trees, not ragweed. Birch pollen around Anchorage can get so bad that even people without allergies get bogged down.

“For a ‘high’ pollen count, you need greater than 175 grains per cubic meter,” Demain said. “In Alaska, we get highs between 2,000 and 4,000 grains per cubic meter.”

In addition to the quantity of pollen, Demain noted that rising carbon dioxide concentrations increase the amount of allergenic peptides on pollen. The peptides are the molecular signal that triggers the body’s immune system, so more peptides on a given pollen grain increases the severity of the allergy.

So it’s not just more pollen; the pollen itself is becoming more potent in causing an immune response.

Allergies are going to get way, way worse

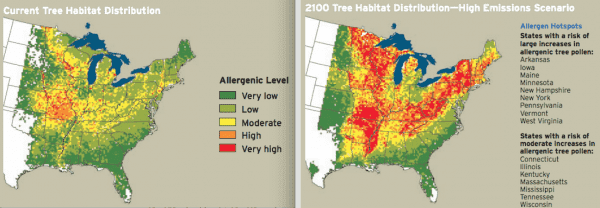

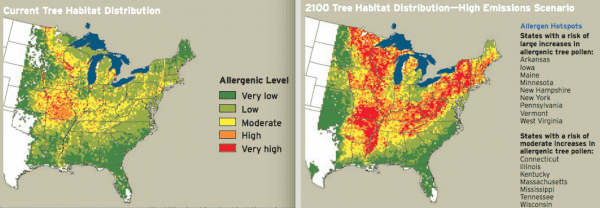

Researchers estimate that pollen counts of all varieties will double by 2040 in some parts of the country, depending on what pathway the world takes on greenhouse gas emissions. Here’s what scientists project allergy risks from tree pollen will change in the eastern United States under a “high” greenhouse gas emissions scenario:

Here’s the trajectory for ragweed:

And here’s what to expect for grass pollen:

This means that regardless of your pollen of choice, the future holds more misery for allergy sufferers.

It’s hard to tell what’s in store for this year in particular, though. Pollen is already hitting Texas “like a punch in the face,” but spring hasn’t yet blossomed in New England as the region hunkers down for its third nor’easter this year, following a relatively warm winter and a year with some of the highest temperatures ever. So scientists aren’t sure whether the cold snaps will dampen the brewing surge in pollen along the Eastern Seaboard.

“From our standpoint, it’s been a very confusing season,” Ziska said.

For now, keep the Benadryl close by.

Sourse: vox.com