“The safest level of drinking is none.” This was the stunning conclusion of a big paper appearing last week in the Lancet — one that prompted dozens of news stories warning of the dangers of even the lowest levels of alcohol consumption.

The researchers wanted to estimate alcohol use and the burden of alcohol-related disease in 195 countries. So they looked at more than 700 studies from around the world, involving millions of people, and came up with a statement about what safe drinking looks like.

Their reasons for going to all this trouble were clear: Alcohol is a massive health and social problem worldwide. Excessive drinking can, over time, increase the risk of everything from liver disease to high blood pressure, injury, and memory and mental health problems. So getting a sense of the global health impact of drinking — the seventh leading risk factor for premature death and disease overall, they determined — was a worthwhile effort.

“But while the paper is so nice and so useful [at estimating alcohol’s disease burden],” Stanford meta-researcher John Ioannidis told me, “at the last moment it destroys everything.” Instead of focusing on the message about the dangers of excessive drinking, “it focuses on making a claim that no alcohol use is safe.”

Not only did the data in the paper not support a zero drinks recommendation, but the authors were also guilty of doing what too many nutrition researchers do: They used definitive, causal language to talk about studies that are only correlational. That’s something Ioannidis, a longtime critic of nutrition science, recently called out as a major source of confusion for the public. In a new paper, he argues that the field of nutritional epidemiology is in need of radical reform.

The alcohol study, and the discussion around it, encapsulates everything that’s wrong with nutritional epidemiology and the way we talk about it. To avoid getting duped in the future, here’s what you need to know.

The way we talk about nutrition science is wrong

Most of what we know about nutrition’s effects on chronic disease comes from observational studies. With them, researchers track what large numbers of people eat over time and then look at their rates of disease, trying to tease out relationships in the data and generate hypotheses for future research. Do people who drink more red wine have lower rates of heart disease? Is eating yogurt and nuts linked with a longer lifespan?

These studies aren’t controlled like randomized trials, where study participants are randomly split into groups and assigned to different interventions. That means the authors of observational studies can’t actually tell us whether one thing caused another thing to happen — only that two things are associated.

Observational studies are also riddled with confounding factors, the unmeasured variables that may actually give rise to certain outcomes.

For example: Say you want to compare people who drink spirits and beer to wine drinkers. These two groups of people might have other differences at the outset aside from their choices of boozy beverage. As we saw with another recent alcohol study, beer and spirit drinkers were more likely to be lower income, male, and smokers and to have jobs that involved manual labor, compared with the wine drinkers. They had a higher risk of death and cardiovascular disease compared to wine drinkers, but was it those lifestyle factors — or just their choice of beer and spirits — that caused their disease risk to shoot up? Researchers try to control for these confounders but they can’t capture all of them.

And even in the best-controlled studies of eating and drinking it’s just incredibly difficult to tease out whether a single nutrient, food, or drink truly caused a specific health outcome.

As Ioannidis points out in his new paper, “Individuals consume thousands of chemicals in millions of possible daily combinations.” We also prepare our foods in thousands of different ways, and when you add one thing to your diet, you take another away. Teasing out the influence of these variables on health outcomes is “challenging, if not impossible,” Ioannidis added.

That’s why observational studies in nutrition are only supposed to be hypothesis generating, not a source for definitive statements about how a single food or nutrient increased or decreased the risk of a disease by a specific percentage.

You wouldn’t know that if you read the conclusions of nutrition studies and especially much of the reporting on nutrition studies. If someone meta-analyzed the evidence from cohort studies (a type of observational research) on various foods, Ioannidis writes, tongue-in-cheek:

All of these claims can’t possibly be true, and yet we often use this type of causal language to talk about nutrition results.

“Readers and guideline developers may ignore hasty statements of causal inference and advocacy to public policy made by past nutritional epidemiology articles,” Ioannidis suggested in his new paper. And we — journalists, researchers, policymakers should avoid making these types of statements based on nutritional epidemiology altogether.

What the new alcohol paper really showed

But unlike the spurious conclusions Ioannidis cited — about how eating a little bacon or an egg will shave years off your life — heavy levels of alcohol consumption have been proven to have terrible health consequences.

“If eggs are bad, even if you eat eight eggs a day, this is no big deal, while with eight drinks of alcohol a day, the risk of disease and death is tremendous,” Ioannidis summed up. And since heavy drinking isn’t socially acceptable, there’s a high degree of under-reporting that happens and a real chance that alcohol’s actual burden is underestimated.

While no one disputes the damaging effects of heavy drinking, there is a lively debate about what constitutes healthy moderate drinking (and concern about the alcohol industry biasing research about the benefits of light drinking). But the new Lancet paper went much further and made the bold claim that people should drink nothing because even a single drink per day is problematic.

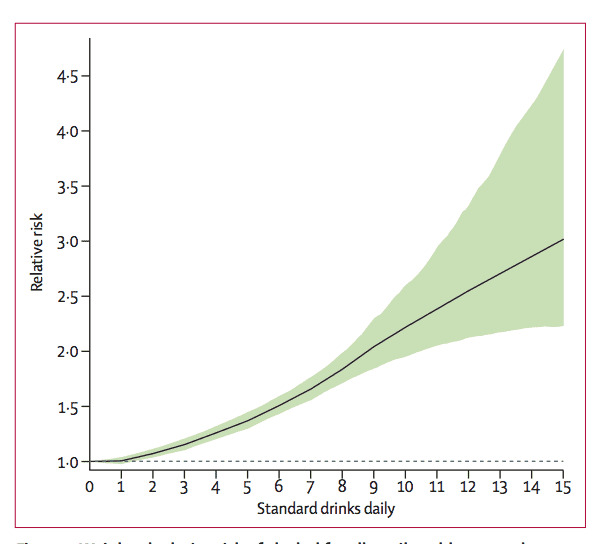

To understand why this assertion is absurd, take a look at this figure from the study, which tracks how the risk of alcohol-related health problems increases by the number of drinks consumed each day:

The authors focused on the risk increase between zero and one drinks per day, and suggested “consuming zero standard drinks daily minimized the overall risk of all health loss.” Yet you’ll notice the risk between zero and one, in the bottom left corner of the chart, is virtually indistinguishable. In fact, the risk curve only starts to increase after one drink, or even 1.5.

So that’s why suggesting people don’t drink anything based on this data is misleading, Cecile Janssens, a research professor of epidemiology at Emory University, told Vox. “This paper shows that very heavy drinking is unhealthy,” she said, “but it doesn’t show that zero drinks is the safest.”

The major result in the paper’s press release, and the one most highlighted in the news coverage, was that adults who consumed a single alcoholic beverage per day increased their risk of 23 alcohol-related health problems (from cancers to cardiovascular disease and personal injuries) by 0.5 percent compared to non-drinkers.

Over at the New York Times, Aaron Carroll did a great job of putting this risk into perspective. A 0.5 percent relative risk increase between no drinking and one-drink-a-day means four more people in 100,000 per year will experience an alcohol-related problem. Here’s Carroll:

Put another way, statistician David Spiegelhalter estimated that 25,000 people would need to drink 400,000 bottles of gin to experience one extra health problem compared to non-drinkers, “which indicates a rather low level of harm in these occasional drinkers.”

So again, the difference in health risk between those who drink nothing and those have one daily drink is tiny. And given the weak observational research it’s based on, potentially not meaningful.

“Telling people not to drink anything is a stretch,” Ioannidis said. “We really need to have large randomized trial evidence to be able to make such a recommendation, and we don’t have one.”

So for now, we don’t know the precise threshold over which alcohol consumption gets risky, but based on this study, it certainly looks like more than zero drinks. So perhaps the question is why the study authors, and the Lancet press office, stretched their findings so far. If I’m being generous, I’d say they were driven by a desire to draw attention to alcohol’s great health burden. But I think they were also playing into the public’s desire for wild nutrition claims — a desire we need to stop feeding.

Sourse: vox.com