Wildfires, hurricanes, and extreme heat used to follow seasonal rules. They increasingly don’t.

Rebecca Leber is a senior reporter covering climate change for Vox. She was previously an environmental reporter at Mother Jones, Grist, and the New Republic. Rebecca also serves on the board of the Society of Environmental Journalists.

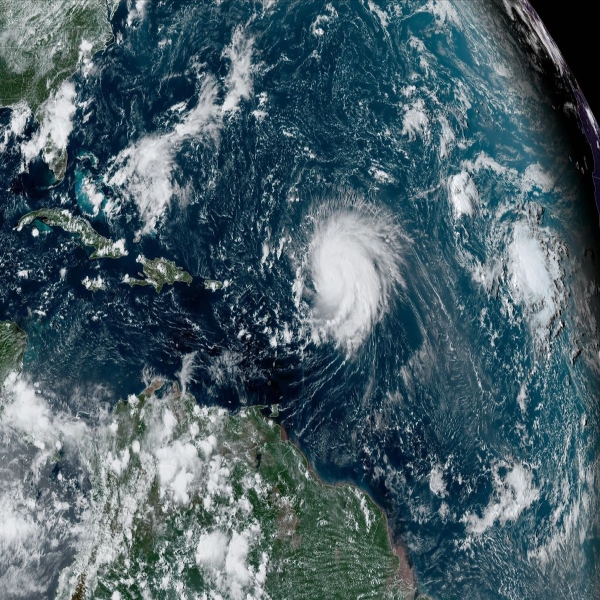

The wave of unusual disasters this summer now includes Hurricane Lee, a storm that swelled from Category 1 to Category 5 in just 24 hours as it barreled toward Canada. It’s a prime example of rapid intensification made worse by warming ocean temperatures.

It will add to what’s already been an exceptional year of extreme weather. The US has set a new record for the number of billion-dollar disasters in a year — 23 so far — in its history, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). And this doesn’t even include the costs from Tropical Storm Hilary in California or from the ongoing drought in the South and Midwest, because those costs have yet to be fully calculated.

“Seemingly no part of the country has been left unscathed,” Ko Barrett, NOAA’s climate adviser, told Vox.

Globally, it’s a similar picture. The European Union’s Copernicus Climate Change Service recently determined that it’s been the hottest summer since records began, beating the last record set in 2019 by a significant margin. The group reported that both July and August reached global average temperatures around 1.5 degrees Celsius warmer than preindustrial times. These are the same average temperature increases that scientists have warned will mean irreversible, widespread crises around the planet.

This summer has seen a rising number of “compound events,” disasters occurring simultaneously or hitting one after another, according to climate scientist Katharine Hayhoe. In some cases, one event might accelerate another. A heat wave, drought, and wildfire can conceivably all hit the same area, for example, and even raise the risks of flooding if a storm finally comes, because the ground is too parched to absorb the influx of water.

And there may be worse to come. Disaster season — or at least, what we’ve historically thought of as disaster season — is hardly over yet. Summer and fall are typically prime times for extremes, but this year we also have El Niño, the natural cycle when Pacific waters reach higher-than-average temperatures, which is just starting to ramp up. This is why meteorologists expect an extraordinary fall to follow the unprecedented summer, likely filled with active hurricanes and warmer weather through the winter.

With El Niño amplifying the effects of climate change, what we can expect from seasons is rapidly changing. Instead of a singular type of disaster any given region must prepare for, but places all over the world can expect multiple events at once. That means our traditional idea of disaster season no longer holds. What we now have is an extended practically year-round calendar of disasters, which often all hit at once.

This summer, extreme weather became more personal

That disasters are becoming more extreme is obviously a problem, but the fact that they’re also compounding so they seem to be everywhere at once is arguably worse. It’s a particular challenge, because compound events can strain first responders and supplies. It’s also brought the destructive effects of climate change to billions of people globally.

In August alone, Hurricane Idalia overwhelmed southeastern Florida’s shores with a record-breaking storm surge of up to 16 feet, wildfires scorched an unusually dry Hawaii and Louisiana, and southern California saw mudslides and flooded roads from heavy rainfall (as well as an unusual tropical storm warning for Hurricane Hilary). A record number of Americans have also been exposed to more smoke in just the first eight months this year than they typically inhale in an entire year.

Meanwhile, this summer has been one of the hottest ever recorded. In the US in July, a third of the entire population faced heat alerts at once. The science nonprofit Climate Central found almost half the world’s population experienced unusual heat attributable to climate change this summer — precisely, at least 30 days of hotter temperatures. And the poorest countries were three times more likely to be exposed to warmer-than-average temperatures than richer countries, meaning the people who contribute the least to the causes of warming are bearing worse impacts.

“In every country we could analyze, including the southern hemisphere where this is the coolest time of year, we saw temperatures that would be difficult — and in some cases nearly impossible — without human-caused climate change,” said Andrew Pershing, Climate Central’s vice president for science.

While temperature fluctuations are a normal feature of the Earth’s climate, there’s ample evidence greenhouse gas emissions from burning fossil fuels are fueling these new extremes. And this summer is just a taste of what’s to come as crises multiply and seasons shift.

Extreme weather is shifting geographically and in timing

September is supposed to be the start of the climatological fall, but the first couple weeks so far have ushered some of the hottest weather yet for parts of the US. Other kinds of extreme events, like wildfires and hurricanes, operate on a slightly different schedule. Hurricane season, as defined by NOAA, lasts from the beginning of June through November 30, and wildfire season can reach its peak in the fall, making September more of a mid-way point.

All this is shifting, though. It helps to think of extreme weather as requiring a set of conditions that come together for a powerful result. In certain seasons, you’re likely to have all the ingredients — high heat, dry soils, high ocean temperatures, and so on — ready to fuel frequent, major disasters.

Even without climate change, you can get the occasional May hurricane or disastrous winter wildfire. But climate change is cranking up the heat, making it more likely that all these ingredients can come together and do so outside of expected seasons. Warmer temperatures can create the perfect conditions for extreme weather at unusual times of the year. Indeed, the start of the hurricane season is actually trending earlier: Eight of the last nine years saw a tropical storm before the traditional June 1 start to the season.

Wildfires have an even less predictable season than heat waves and hurricanes, but they have been more frequent throughout the year, burning more area in the past 20 years than in the decades that came before. And the smoke from these fires is having an even wider impact. Canada’s worst wildfire season on record, particularly in the eastern part of the country, has blanketed the Northeast and Midwest with smoke for parts of the summer.

“Extreme drought across Canada led to one of the worst wildfire seasons on record, with lots of fuel and prolonged dryness contributing to this set of events,” Barrett said. “All of which is associated with our warming planet. When combined with the right atmospheric set-up, a rarely seen extreme can occur.”

The atmospheric conditions this fall are still ripe for disaster — and the possibility that disaster season will linger long past its usual deadline. El Niño is also a multiyear event, scientists worry that next year may be even hotter. And with El Niño exacerbating the warming the world has already experienced, everyone should expect even more extreme weather.

“El Niño is just ramping up,” Hayhoe said. “It’s like we’re a frog in a pot of slowly boiling water and somebody just poured a kettle full of more boiling water into the pot.”

When the El Niño cycle eventually ends, the world can’t expect a return to normalcy. We’re on a path for more extremes that will accelerate for decades to come.

Source: vox.com