Scott Dowell, an infectious disease doctor, has helped respond to more than a dozen Ebola outbreaks in the last two decades. But the one that’s currently ravaging the Democratic Republic of Congo is different from all the others he’s seen: For the first time in history, Ebola is spreading in an active war zone.

Just before his arrival in September, two large attacks in and outside Beni — where Dowell, the deputy director for surveillance and epidemiology at Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, was working — killed more than 30 people, bringing the total number of civilian deaths in DRC this year to 235.

“The population is going about their daily business,” Dowell said. “But then we’d have these episodes where it really is dangerous. There were a couple of nights we heard shooting and saw people running down the street in front of the place we were staying.”

The Ebola outbreak happening amid this havoc was declared on August 1, a week after another Ebola flareup in Western DRC ended. Since then, nearly 200 people have gotten sick with the virus, including 122 deaths — making it one of the largest Ebola outbreaks in history.

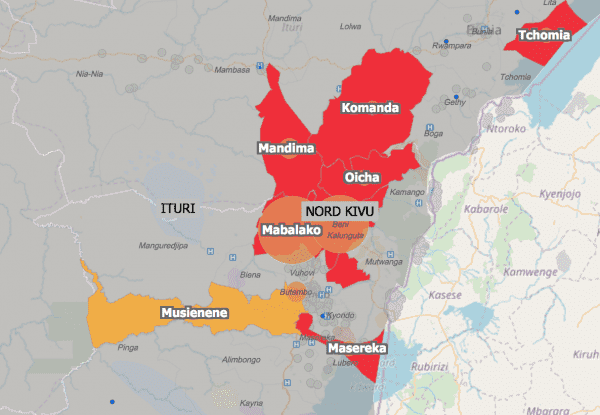

It’s also proving to be one of the most challenging to control. The virus is spreading in North Kivu and Ituri, provinces in Eastern DRC on the border of Rwanda and Uganda. There, armed opposition groups have been carrying out deadly attacks on civilians, which are forcing people from their homes. More than a million people are displaced in the area, according to the United Nations Refugee Agency.

This sporadic violence and chaos are shaping up to be the global community’s greatest Ebola test since West Africa in 2014. Back then, health groups, especially the World Health Organization, were widely criticized for responding too slowly, and allowing the outbreak to spin out of control.

The latest DRC response is a stark contrast to that, Dowell said. Ebola vaccinators were on the ground within a week of the outbreak being declared. And, according to the WHO, if you count up all the NGOs, the WHO, and local staff, there are already 450 responders.

But the violence and instability in Eastern Congo is testing the limits of these responders and even an effective Ebola vaccine.

“Ebola outbreaks have been in fragile states and environments but not where there’s outright armed conflict,” said Peter Piot, director of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, who has worked on Ebola since its discovery in 1976. “The Congolese are doing their best. The WHO is really passing the test and doing everything they can. But they are in a situation that’s not fully under their control.”

How Ebola responses are supposed to work

Before we go any further, a quick primer on Ebola basics. The virus is spread through direct contact with the bodily fluids, like vomit, urine, or blood, of someone who is already sick and has symptoms. The sicker people get, and the closer to the death, the more contagious they become. (That’s why caring for the very ill and attending funerals are especially dangerous.)

When the disease strikes, it’s like the worst and most humiliating flu you could imagine. People get the sweats, along with body aches and pains. Then they start vomiting and having uncontrollable diarrhea. They experience dehydration. These symptoms can appear anywhere between two and 21 days after exposure to the virus. Sometimes patients go into shock. In rare cases, they bleed.

Because we have no cure for Ebola, health professionals use traditional public health measures: finding, treating and isolating the sick, and breaking the chains of transmission, so the virus stops spreading.

In every Ebola outbreak, public health officials mount vigorous public health awareness campaigns to remind people to wash their hands, that touching and kissing friends and neighbors is a potential health risk, and that burial practices need to be modified to minimize the risk of Ebola spreading at funerals.

They also employ a strategy called “contact tracing”: finding all the contacts of people who are sick, and following up with them for 21 days — the period during which Ebola incubates.

This time, they also have an additional tool: an effective vaccine.

But responders first need to find those who need it: Instead of vaccinating the entire population, they’re doling out the shots through a “ring vaccination” strategy, which involves immunizing the contacts — friends, family, housemates, neighbors — of people who have fallen ill to create a protective ring around them to stop transmission.

Then they need to convince people to take the vaccine. And doing both of these things is proving difficult in Eastern Congo.

Why this outbreak is different

The outbreak, identified in August, actually started in July in a village called Mangina, in the Mabalako district of North Kivu province. New cases quickly spread outward, reaching a neighboring province, Ituri. Within weeks, a second epicenter in the outbreak emerged in Beni, 160 miles from Mangina. And after a lull in early September, there’s been an upswing in cases this month, directly related to the violence playing out in Beni, said Dr. Ibrahima-Soce Fall, the WHO regional emergency director for Africa.

“The fighting and armed attacks around Beni [in September], killed a lot of civilians, and there were demonstrations in the city,” he told Vox. “For three to four days, the Ebola operation was stopped. There was no possibility to identify cases or contacts, to vaccinate.”

This meant health responders missed cases, who may have spread the virus to their contacts. “If we have any disruption, [that] will lead to another cycle of infection transmission. We don’t want one single day of disruption.”

In addition, convincing people to report and isolate sick family members isn’t straightforward in a place like North Kivu. “This area has been exposed to armed groups for more than 20 years. You can imagine the level of distrust [of health responders],” Fall said.

According to an August survey of nearly 600 Eastern Congolese published October 5 in the Lancet, 17 percent said they wouldn’t send a family member suspected of being infected with Ebola to a treatment center. About the same percentage said they’d hide sick family members from the authorities.

The most recent Ebola report on the outbreak from the WHO noted that one person escaped from a treatment center and still hasn’t been found. Yesterday, the body of a woman who died in a treatment center was stolen by community members, according to the DRC health ministry.

Then there’s the violence against health workers. After an attack on Red Cross volunteers who were helping to safely bury an Ebola victim in September, the government resorted to deploying security forces to help with safe burials, according to Al Jazeera.

The Lancet survey uncovered one bright spot: acceptance of the Ebola vaccine appears to be high. Eighty-two percent of respondents said they’d take vaccines for their family members. But again, health responders need to find people in order to vaccinate them.

“Vaccination doesn’t replace the classic [Ebola response] measures,” Piot said. “It’s not that it’s the magic bullet. So it’s really absolutely essential to continue to do all the rest.” And doing so amid violent flareups is not a simple task.

Sourse: vox.com