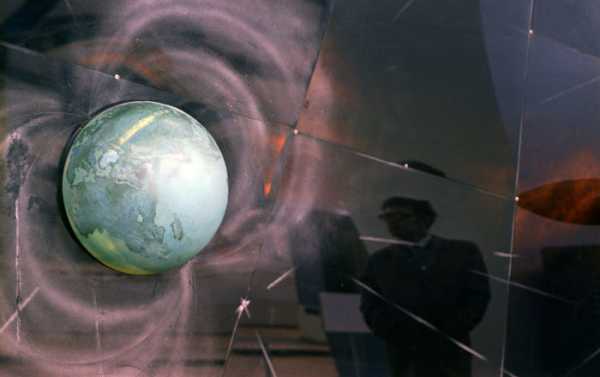

The study suggests that it was the molten part of Earth’s mantle, and not the core, that might’ve generated the magnetic field during the planet’s early years.

A new study conducted by researchers from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego may offer a new intriguing insight into the history and nature of our planet’s magnetic field, according to a press release issued by the university.

The study, published in the Earth and Planetary Science Letters journal on 15 March, reportedly offers “new estimates for the thermodynamics of magnetic field generation” in the liquid part of Earth’s mantle, and provides a “door-opening opportunity to resolve inconsistencies in the narrative of the planet’s early days”.

As the release points out, the basic tenets of geophysics state that the liquid core of our planet always served as “the source of the dynamo” that generates Earth’s magnetic field.

However, in 2007, scientists in France postulated that the bottom third of Earth’s mantle was molten during the first half of the planet’s 4.5 billion year history; and six years later, Stegman and his co-author Leah Ziegler first moved to expand on this hypothesis, postulating that it was that very part of the mantle (the “basalt magma ocean”, as the French researchers called it) that might’ve produced the planetary magnetic field at that time.

Stixrude’s research, published in Nature Communications on 25 February, reportedly shows that he and team “found very large values of the electrical conductivity, large enough to sustain a silicate dynamo.”

And in a separate study, Arizona State geophysicist Joseph O’Rourke used Stegman’s concept to try and determine whether Venus might’ve generated a magnetic field with a molten mantle in the past.

These three studies, the release claims, show that that the new theory regarding the nature of the planetary magnetic field is “starting to take hold”, though it is still “far from being widely accepted”.

Sourse: sputniknews.com