Jupiter is often described as a solar system in miniature. The gas giant is made out of the same basic ingredients as the sun — hydrogen and helium — and is surrounded by an array of geologically diverse moons.

Today, the Jupiter system grows even more impressive. The International Astronomical Union has confirmed the discovery of 10 new moons, bringing the grand total to 79. This discovery includes one very odd moon that helps explain why there are so many others.

Where have these moons been all this time?

How could 10 moons just go unnoticed, you ask?

The short answer: These moons are relatively tiny, just a couple miles across or smaller. And even with high-powered telescopes, it can be very hard to spot small, dim objects next to something as massive and luminous as Jupiter.

“As our technology gets better and better, we’re able to look fainter and fainter, so we’re discovering smaller and smaller moons,” said Scott S. Sheppard, the Carnegie Institution for Science astronomer who led the discoveries.

These new moons were discovered using a 520-megapixel camera attached to the huge Victor M. Blanco Telescope in Chile. (For reference: The latest iPhone has a 12-megapixel camera.) The camera not only has a dense resolution, it’s also specially calibrated to find faint objects.

Also, Jupiter’s gravity is so strong, it can keep objects in orbit up to 18.6 million miles away. (Recall that our moon is just 239,000 miles away.) This means there’s a lot of space around Jupiter for astronomers to examine that could possibly contain moons.

How to discover moons of Jupiter

Sheppard and his team weren’t actually looking for the new moons when they discovered them — they were looking for other far-flung and hard-to-spot objects out past Pluto.

When their telescope scans the sky, it takes in objects at all distances. It can spot stars millions of light-years away. It can spot Kuiper belt objects near the edge of the solar system. And it can see objects closer to home, like the eight planets. All of those objects could be in the same image.

It’s the motion of these objects over a period of time that tells astronomers what and where they are. “It’s like when you’re driving in your car,” Sheppard explains. “When you look out the side of the road, the street signs are flying by really fast as you are driving, and the mountains in the background are moving very slow.” Slower objects are farther away. And if an object is moving at the same speed as Jupiter, it’s likely in the same location.

The team first noticed the moons in 2017, but they needed a year of follow-up observations to chart the shape of their orbits and to confirm they weren’t actually asteroids or comets orbiting the sun.

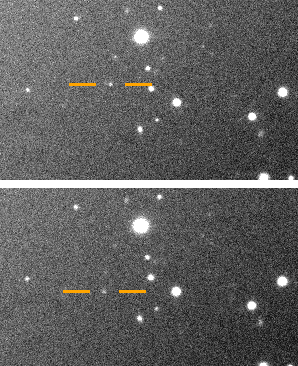

Here’s what the telescope actually captured. Most of the white dots in the photo are stars. But you can see a moon, marked with orange lines on either side, moving ever so slightly from one frame to the next. This was the big clue it was a moon of Jupiter. It was moving against a background of static stars.

Humans have been discovering moons of Jupiter since Galileo spotted the first four large ones — Callisto, Io, Europa, and Ganymede — in 1610.

It’s not exactly a shock that we’re still discovering them, considering how our telescopes are getting better and better at making out the faintest of objects. Two moons were announced just last year. And Sheppard suspects there are still more to find.

Only one of the moons has a name for now. Introducing Valetudo.

Nine of the moons remain nameless (for now). But one special one has been named.

It’s called Valetudo, named after the Roman goddess of health and hygiene. New Jupiter moons are named after Roman gods related to Jupiter. Valetudo is Jupiter’s great-granddaughter. And adorably, Sheppard chose Valetudo as a nod to his girlfriend, whom he describes as a “very cleanly person.”

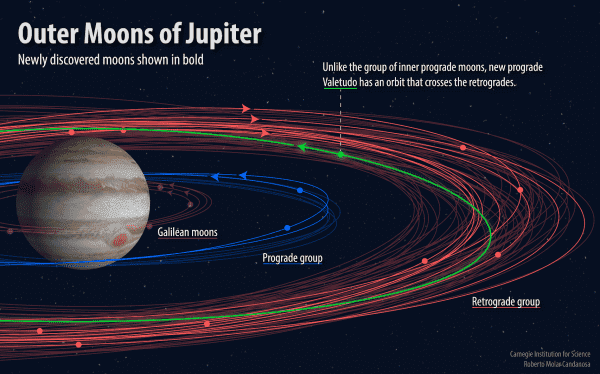

Moons close to Jupiter tend to orbit in a “prograde” motion, meaning in the same direction as Jupiter’s rotation. Those farther away rotate in a retrograde motion. But Valetudo is an odd duck. It’s orbiting in a prograde motion in the retrograde region.

“It’s like driving down the highway the wrong way,” Sheppard says. “It’s going around Jupiter in one direction, and there’s, like, 40-something objects going around Jupiter in the other direction.” This means it’s “very likely to have some sort of head-on collision over time,” he says.

And that’s actually an important clue to why there are so many moons around Jupiter. Sheppard explains that a long time ago, there were probably fewer, larger moons orbiting Jupiter in this retrograde region. But over time, they were broken into pieces.

It’s possible that Valetudo — or a larger previous version of it — was the destructive force behind the collision. Imagine the chaos that would ensue if a tractor-trailer was driving against traffic on a highway; that’s Valetudo. And that possibly “gives us this whole swarm of objects we see today,” Sheppard says.

There’s still a lot that’s unknown about these moons, like what they exactly look like or what they’re made of. NASA’s Juno spacecraft, which is currently orbiting Jupiter, is not in a position to image them. It will take a future mission to Jupiter to get a clearer view of the moons. The only things we know about them are their approximate sizes and the shape of their orbits.

But if we do investigate them further, they might also reveal clues about the origin of our solar system. The outer planets — Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune — were formed by vacuuming up smaller objects in their paths. And the objects that weren’t consumed were captured in their orbits.

“These outer moons,” Sheppard says, “are like the last remnants of the planetesimals, the first objects that formed our solar system.”

Further reading: Jupiter, the king of planets

- The awesome beauty of Jupiter captured by Juno, in 13 photos

- Why NASA’s Juno Jupiter orbiter is a big deal

Sourse: vox.com