Last summer, I published a comprehensive guide to the new science of treating back pain. Immediately my inbox filled with emails about a doctor that readers felt I’d overlooked: the late John Sarno.

“Thousands of people, including myself and my husband, cured our chronic back pain using [Sarno’s] methods,” wrote Karen Karvonen. Another Sarno devotee, Steven Schroeder, said the doctor changed his life. Schroeder’s back pain flared whenever he was stressed — a busy time at work, an illness in his family. After he absorbed Sarno’s books, the discomfort mostly vanished.

“I still sometimes have pain now in times of stress — but I can literally make it go away with mental focus,” Schroeder, a lawyer in Chicago, wrote in an email. “It is crazy.”

Though he may not be a household name, Sarno is probably America’s most famous back pain doctor. Before his death on June 22 2017, a day shy of his 94th birthday, he published four books and built a cult-like following of thousands of patients — including Howard Stern and Larry David. Many of them claim to have been healed by Sarno, who essentially argued back pain was all in people’s heads. And Sarno himself often said that some 80 percent of his patients got better.

Related

100 million Americans have chronic pain. Very few use one of the best tools to treat it.

I first came across the back pain guru in my research for our comprehensive guide. But I was skeptical of his theories, which were largely based on hunches and anecdote. He admitted that he never tested his ideas with controlled studies, saying he’d rather spend his time healing patients at his New York University practice than doing research. At first glance, he seemed like an outdated Freudian.

Beloved by his patients, Sarno was also derided by his medical peers. He didn’t have much of an influence on medical research during his lifetime. Tellingly, his NYU colleagues never referred their patients to him.

“It is not really credible to claim that you can cure 75 percent or more of patients with chronic low back pain, especially since no one has been able to duplicate these kinds of results or even close to it, as far as I’m aware,” said Roger Chou, a back pain expert and professor at Oregon Health and Science University.

But even if Sarno didn’t play by the rules of science, he endures. He inspired people — and still does. He managed to write best-selling books and attract patients from across the country to NYU. He’s the subject of a 20/20 feature and a recent documentary, All the Rage: Saved by Sarno, that was screened around the world. Sarno’s followers continue to record their stories on their “Thank You, Dr. Sarno” project. “I know you never liked hearing it, but I owe my life to you,” Ted H. wrote on the blog.

After digging a little deeper, I learned that some of Sarno’s theories are now even being validated by science — specifically, that there can sometimes be an emotional basis for chronic back pain. And that’s an important truth mainstream pain medicine still hasn’t quite figured out what to do with.

Sarno believed our brain used pain to distract us from experiencing negative emotions

Lower back pain is among the chief reasons people go to see a doctor in the US, and nearly a third of American adults say they’ve been afflicted. The US spends approximately $90 billion a year on back pain — more than the annual expenditures on high blood pressure, pregnancy and postpartum care, and depression — and that doesn’t include the estimated $10 billion to $20 billion in back pain-related lost productivity.

Doctors have overwhelmingly failed people with back pain. Many of the most popular treatments on offer — bed rest, spinal surgery, opioid painkillers, steroid injections — have been proven ineffective in the majority of cases, and sometimes downright harmful. Only in the past couple of years, with the rise of the opioid epidemic, has the medical establishment begun to acknowledge this failure and suggest people explore alternatives for their sore backs.

Enter John Sarno. A specialist in rehabilitation medicine, he had very different notions about the causes of back pain than his medical peers. Sarno was most active during the 1980s and ’90s, a time when back discomfort was thought to arise mainly in the presence a mechanical problem (a bulging disc, say, or joint arthritis). Instead, he argued the pain was actually the result of a psychosomatic process and emotional factors.

More specifically, he believed that the brain distracts us from experiencing negative emotions by creating pain. We may not want to accept the uncomfortable truths that we are angry with our children, or that we hate our job, so instead of thinking those thoughts, we focus on the pain.

He also thought that pain was created by reduced oxygen and blood flow to the muscles and nerves of the body. So our brains unconsciously direct blood away from certain areas of our body, and that creates pain. (If this focus on the unconscious mind sounds familiar, it’s because Sarno was heavily influenced by Freud. His book The Divided Mind was all about psychosomatic medicine, including Freud’s pivotal influence.)

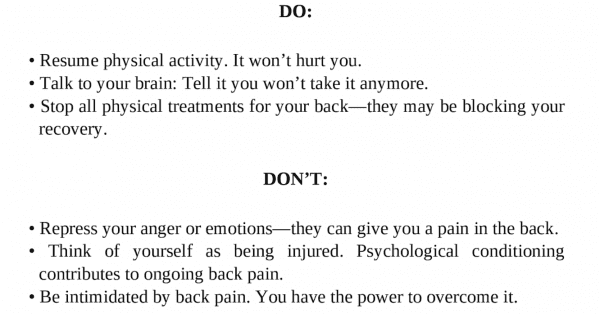

Sarno coined a term for his diagnosis — “tension myoneural syndrome” — and believed many people could overcome their pain simply by acknowledging its psychosomatic origins. He instructed many of his patients to journal or seek out psychotherapy to gain a better understanding of the emotions they were repressing that generated their chronic back pain. He also advised they immediately resume physical activity, that it would make them better and not worse.

To get a feel for his approach, here are some of the dos and don’ts from Healing Back Pain, published in 1991:

Many doctors still think Sarno’s views on back pain are off

Back pain researchers and doctors generally didn’t find Sarno convincing — and many still don’t. Andrea Furlan, a psychiatrist who has published numerous systematic reviews on back pain, says the big problem with Sarno’s approach was that it was too “one-size-fits-all.” Some people’s back pain may be exacerbated by emotional problems or stress, but not everyone’s. “I think it is a mistake to generalize [the mind-body model] to all people with back pain,” Furlan said.

“Blaming this all on repressed emotions is a pretty narrow view of psychological contributors to pain,” Oregon’s Chou added. “It ignores a lot of what we understand now about changes that occur centrally in persons with chronic pain.” For example, we now have MRI studies showing that people with chronic pain have different areas of their brain light up when they are exposed to painful stimuli.

“Sarno had no interest in seeing brain MRIs,” said Cathryn Jakobson Ramin, author of the book Crooked: Outwitting the Back Pain Industry and Getting on the Road to Recovery. “He was actually very limited in his scope … until his last days, stuck in a Freudian mindset, viewing what was going on with patients as evidence of psychological problems rather than neurological problems.”

The mechanism Sarno proposed — about decreased blood flow caused by the brain — was also never supported by science, explained Howard Schubiner, who heads a mind-body medicine program at Providence Hospital in Michigan, which was inspired by Sarno’s work. “It made no sense to a lot of scientists and physicians.”

But there are some things Sarno got right, Schubiner added. “The science is catching up to Dr. Sarno.”

Sarno got some things right

It’s now mainstream to view chronic back pain as a “biopsychosocial” condition — meaning biological factors (such as a person’s weight or spine structure) may play a role but psychological and social factors can too. Researchers have found, for example, that people who are under stress or are prone to depression, catastrophizing, and anxiety tend to suffer more with chronic back pain, as do those who have histories of trauma in their early lives or poor job satisfaction.

“Was [Sarno] the first person to discover the mind-body connection? Of course not,” said Schubiner. “But Sarno popularized it [in the area of back pain].”

A new understanding of pain, commonly referred to as “central sensitization,” is also gaining traction. The basic idea is that in some people who have ongoing pain, there are changes that occur between the body and brain that heighten pain sensitivity — to the point where even things that normally don’t hurt are perceived as painful. That means some people with chronic low back pain may actually be suffering from malfunctioning pain signals. So again, it’s what’s going on in the mind that matters for their pain, more so than what’s going on in their bodies.

Now, this doesn’t mean everybody’s back pain has a psychological root cause. It also doesn’t mean the mechanism Sarno suggested — decreased blood flow created by the brain — has been validated, or that it’s repressed emotions that hurt people. But Sarno was ahead of the science with his broader mind-body approach.

Sarno-esque approaches are slowly catching on

There were other things Sarno got right, whether or not the science of his time backed him up. He was also a strong advocate that people with back pain shouldn’t take bed rest and stop their daily activities, which were pretty mainstream remedies in the 1980s and ’90s, when he was publishing his books.

Doctors now think that bed rest is a very bad idea in most cases, and studies comparing exercise to no exercise for chronic low back pain are consistently clear: Physical activity can help relieve pain, while being inactive can delay a person’s recovery.

“What he recommended as treatment was essentially cognitive behavioral therapy — elimination of fear avoidant behavior and catastrophizing — before anyone had ever heard of it,” Ramin said, “and it’s exactly what is being used now to treat patients with central sensitization.”

Sarno-esque approaches are slowly catching on for back pain. The evidence is mounting for “multidisciplinary rehabilitation,” for example. This approach views back pain as the result of the interplay of physical, psychological, and social factors. Practitioners do things like help patients get treatment for their depression or anxiety, or guide them through cognitive behavioral therapy to improve their coping skills as part of their back pain therapy. (As I noted in my guide to back pain science, multidisciplinary therapy appears to work slightly better than physical therapy alone for chronic back pain in both the short and long term.)

Since these approaches have been shown to meaningfully improve chronic pain, researchers would like to see them offered more frequently than they are now, Vox’s Brian Resnick reported.

Schubiner has co-authored several studies looking at the impact of Sarno-style pain management. The most recent, published in the journal Pain, was the first large-scale randomized controlled trial to show that guiding people with chronic pain (in this case, caused by fibromyalgia) through how to process and express powerful emotions such as anger worked better than regular cognitive behavior therapy at reducing fibromyalgia symptoms.

Sarno also intuitively understood that anatomical abnormalities like lumbar disc bulges are not actually the source of pain for many people — and called these injuries “normal abnormalities.” Research over the past two decades has piled up to prove him right. For example, when you compare people with the same MRI results showing the same back injury — bulging discs, say, or facet joint arthritis — some may experience terrible chronic pain while others report no pain at all.

After testing Sarno’s methods, Schubiner now thinks the people who say they have been cured by Sarno are probably a minority of outspoken patients with back pain that happens to be exacerbated by stress or emotional problems. That means there are people out there with chronic pain who could benefit from psychotherapy. But that’s not true for every back pain patient. (And there are surely other people who didn’t experience life-changing healing after reading Sarno but are less likely to speak up.)

At the end of the Sarno documentary, his fans from the “Thank You, Dr. Sarno” project present him with a book of people’s healing stories. Sarno says, “All of this because of one simple idea: the fact that the mind and the body are intimately connected. That’s it. That’s the whole story.”

Michael Galinsky, the maker of the documentary, told me this line from the documentary resonated. “While that might seem to be an obvious truth, the biotechnical approach to medicine essentially negates it in regards to practice,” Galinsky said. That’s now slowly shifting, but it took an unprecedented opioid epidemic — instead of a charismatic doctor — to spur change.

Correction: A previous version of this post misstated the name of the television news program that featured Sarno’s work.

Sourse: vox.com