If you spend a lot of time reading takes on the internet, it seems that no one likes Amazon.

It’s become the prime example of a new argument from the progressive antitrust movement: that current American legal practice is too soft on giant companies.

The Wall Street Journal editorial page has denounced New York for handing out subsidies for Amazon’s new hub. Progressive New York City Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez has done the same.

President Donald Trump routinely slams Amazon for allegedly benefiting from US Postal Service subsidies.

There’s even a big movement afoot among thought leaders to get people to cancel their Amazon Prime accounts — with criticisms mostly focused on the well-documented bleak working conditions in Amazon warehouses.

I personally stand by my argument that — absent some very large additional policy changes — Amazon coming to New York will be bad for the poor and thus is really not an idea that the city and state should subsidize. What’s more, the larger progressive push for a revival and reinvigoration of antitrust enforcement is an important corrective to a regulatory landscape that has become much too permissive in the 21st century.

But Amazon’s response to all this criticism has been business as usual. The reason: Despite this growing chorus of elite criticism, the company is extremely popular. (Even typical New Yorkers love the idea of subsidizing a big new Amazon office park.) Amazon seems to be the most popular company in America, and arguably the most broadly popular institution in America. It’s why the backlash that feels omnipresent on the internet isn’t carrying much weight in the real world.

For anyone who cares about antitrust issues, there are lessons to be learned here that have important implications for how it makes sense to try to tackle the issue.

Amazon is extremely popular

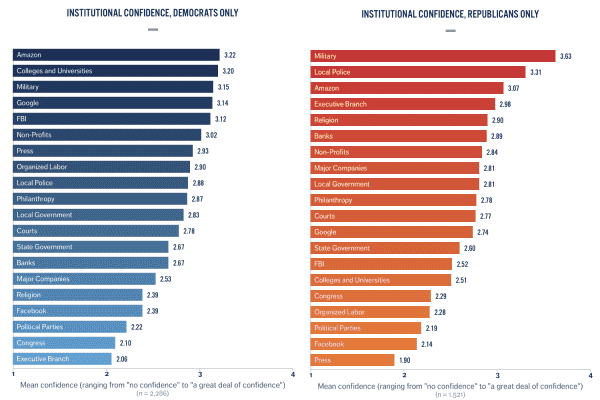

Over the summer, the Baker Center at Georgetown University polled the American public on a range of institutions and found that among Democrats, there is literally nothing that is more popular than Amazon.

Pointy-headed academics, critical journalists, and suspicious members of Congress can complain about Amazon, but it seems it won’t hurt the company that much. Democrats have much more confidence in Amazon than they do in any branch of the American government, in colleges and universities, or in the press.

Republicans, on the other hand, trust men with guns more than they trust the everything store, but Amazon still comes in at No. 3. Republicans trust Amazon more than they trust the Trump-led executive branch, more than they trust religion, and more than they trust the courts or the nonprofit sector.

And accordingly, Amazon coming to New York is overwhelmingly popular. Even when the question specifically calls out the subsidies, the idea is still moderately popular.

People like a good deal

Anti-Amazon advocates are having trouble resonating with the public because, unlike other antitrust cases, consumers don’t feel the pain.

For example, the argument that the Obama administration erred in allowing American Airlines and US Air to merge is not ironclad, but it does have a nice clean structure to it: With so little competition in the industry, airlines have been able to keep fares and fees high even while downgrading the product with concepts like “Basic Economy.”

Similarly, the formation of the AB InBev conglomerate seems to have led to higher beer prices. By contrast, the at the time controversial decision to block T-Mobile and AT&T* from merging unleashed a chain reaction of events that’s brought affordable unlimited data plans to millions of Americans.

This is a view that calls for tougher, more skeptical enforcement of antitrust law but that also leaves the conceptual apparatus of post-Reagan antitrust doctrine in place. The idea is that mergers are bad when they lead to higher prices.

Many Amazon critics, however, want to argue something else: that the sheer scale and scope of Amazon’s operations should be viewed with skepticism. For example, if you want to bring a product to market through online sales these days, the best way is to use Amazon as a storefront. But if your product is really successful, Amazon is liable to use its control of the storefront to gather that data and then start creating a copycat product that undermines your margins. Then Amazon will push its own offering over yours when people are shopping.

That does sound shady. But note that the core complaint is that Amazon is abusing its market power to give you, the consumer, a good deal. This is the opposite of the kind of complaints people have about airlines or cable companies, which are seen as screwing over customers on price.

Most of the complaints about Amazon have this structure. They are abusing warehouse workers to make sure you can get stuff really fast. They are destroying Main Street retailers by selling you stuff for cheap. They are squeezing suppliers. But this argument is much harder to sell to the public when they don’t feel the pain themselves.

Advocates argue there’s more to life than good deals for consumers. And there surely is. Impacts on labor rights, on the overall wage structure of the economy, on the environment, on local communities, and on the larger framework of innovation and competition in the American economy matter. But in lots of low-competition sectors of the economy, the customer experience is very bad, while the customer experience with Amazon is usually quite good. That makes it popular — and it makes winning a political battle with Amazon for the sake of low-income renters or small-business owners or whoever else objectively very difficult, even if it’s rooted in the best intentions.

* An earlier version of this article said it was a merger between T-Mobile and Sprint that had been blocked; in fact, such a merger is currently in the works and it was a merger with AT&T that got blocked.

Sourse: vox.com