What does it mean to say “if you like your health insurance, you can keep it”?

Some will remember this as a defining debate around the Affordable Care Act. One lesson Democrats took from the collapse of the Clinton administration’s 1994 reforms was that Americans hated the idea of the government canceling their insurance plans. In deference to that view, the ACA was designed to leave most existing health coverage intact, and President Obama repeatedly promised that no one would lose insurance they liked. Even so, about 3 million plans did get canceled because they were beneath the ACA’s minimum standards for health insurance, and the political backlash was fierce.

This debate has reemerged in the runup to 2020. Bernie Sanders’s Medicare-for-all plan, as currently written, would cancel every private insurance plan in the country. Polling suggests that’s lethal: When told that Medicare-for-all would abolish private insurance, respondents flip from favoring the plan by a 56 percent to 38 percent margin to opposing it by a 58 percent to 37 percent margin. These numbers, when combined with the Obamacare backlash and the Clintoncare experience, have underscored reformers’ view that a plan that takes away the private insurance people have and like is doomed.

In response, supporters of Medicare-for-all have struck back with an ambitious reframing: The idea that anyone can keep the health insurance they like under any system but Medicare-for-all is the true lie, they say.

Matt Bruenig, of the People’s Policy Project, is the most aggressive proponent of this view. “The truth is that people who love their employer-based insurance do not get to hold on to it in our current system,” he writes. “Instead, they lose that insurance constantly, all the time, over and over again. It is a complete nightmare.” The only way to enjoy true health security, where your insurance can never be taken away, is “a seamless system where people do not constantly churn on and off of insurance. Medicare for All offers that.”

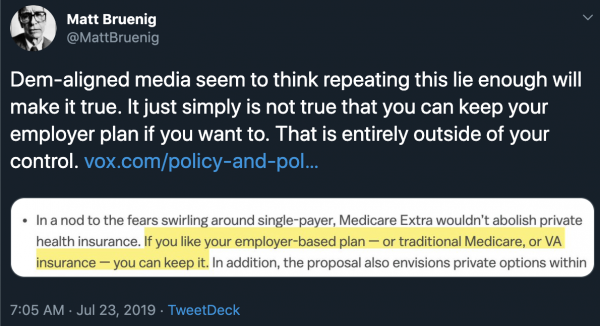

There’s power to this argument. As a comparison between Medicare-for-all and the status quo, there’d be far more security under Medicare-for-all. But even as he accuses others of dishonesty, Bruenig is weaponizing this point against plans that it doesn’t apply to — most recently, the Center for American Progress’s Medicare Extra plan — and doing so in ways that confuse the underlying issue.

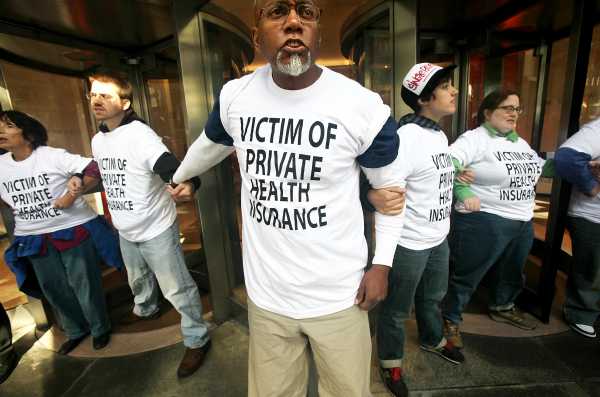

If this were just an internecine debate between supporters of different health reform plans that would all be vast improvements over what we have now, it wouldn’t much matter. But it raises some of the hardest issues in health politics. Private health insurance isn’t theoretical. More than 150 million Americans get insurance through their employers right now. They live in the world that pundits and think-tankers are arguing over. So if the private insurance market as it exists is such a nightmare, then why are people so loath to see it replaced?

This is a question that has crushed past efforts at health reform — and not just federally. In the past few years, Vermont saw its effort to pass single-payer collapse and 79 percent of Coloradans voted down a single-payer ballot initiative.

So why aren’t voters more willing to abandon a system that’s clearly failing? And what kinds of reforms will they accept?

The two types of “insurance churn”

The key idea in Bruenig’s argument is something experts call “insurance churn.” Importantly, though, the term is being used to refer to two different things:

- Researchers use insurance churn to refer to any change in health insurance plans. If I lose my job and become uninsured, that’s churn. If my employer switches insurance providers, that’s churn. If I move from my current job and insurance coverage to another job with a different insurance plan, that’s churn. And so on.

- In punditry, though, people will often simplify churn to the question of losing and gaining health insurance. In this meaning, it’s not churn if my employer switches coverage providers, but it is if my employer fires me and I become uninsured.

You can see the way one definition slides into the other in Bruenig’s post. For most of the analysis, he’s using the first, more technical, definition of churn. He relies on a study of insurance churn in Michigan, for instance, to write:

The study he’s referencing found that “Ninety-four percent of respondents with employer-sponsored plans maintained coverage continuously all year.” The lower, 72 percent number includes data showing that “16 percent directly switched to a different employer-sponsored plan and 6 percent gained coverage through either an individually purchased plan, Medicaid, or Medicare.” So that’s the first type of churn, which includes changes to the plans people use, not just changes to whether people are insured or not.

But at the end, when Bruenig says that Medicare-for-all is “a seamless system where people do not constantly churn on and off of insurance,” he’s quietly switching to the second definition of churn.

The core insight here is real: So long as a third party is providing your health insurance, you don’t have full control of its future. You may like the health plan your employer provides now, but they could change that plan, or you could change jobs, or be laid off. The problem is that point applies to public insurance too.

Imagine President Bernie Sanders passes Medicare-for-all in 2022. In 2024, amid a backlash to rising tax rates, Sanders loses reelection to Ohio Sen. Rob Portman. Working with a Republican Congress, Portman restructures Medicare-for-all in a few ways. Where Sanders included coverage for abortion, Portman bars it totally. Where Sanders designed the program to avoid copays and deductibles, Portman, a believer in health savings accounts, reworks it to frontload the cost-sharing. Where Sanders guaranteed coverage to everyone, including unauthorized immigrants, Portman restricts it to legal residents, and adds a work requirement for able-bodied adults.

If any of that sounds far-fetched, consider that Republicans were a single vote away from repealing Obamacare in 2017, and the Trump administration approved Wisconsin’s request to add premiums and a work requirement to its Medicaid program in 2018.

The skepticism Bruenig brings to private insurance is the same skepticism many bring to single-payer insurance. You like your government-provided health plan? Better cross your fingers, because your side just lost the White House, and the incoming administration wants to slash health care spending by 15 percent, drug-test all beneficiaries, and turn the whole thing over to private contractors.

Not all churn is equal

A problem with the term “churn” is that it collapses both good and bad dynamics into the same label. Involuntary churn is a problem. But voluntary churn typically goes by another name: choice.

Take Medicare Advantage, the suite of private insurance options offered inside the Medicare program. About a third of Medicare enrollees choose Medicare Advantage, and about 10 percent of Medicare Advantage members voluntarily choose to switch to another plan each year. Medicare Advantage’s enrollees are slightly more satisfied with their coverage than those in traditional Medicare, so it’s reasonable to assume they appreciate the opportunity for churn.

Last week, I wrote about the Center for American Progress’s Medicare Extra plan. I won’t recap the entire piece here, but the short version is that Medicare Extra rebuilds the health system around a revamped Medicare plan, but it allows people to remain in employer-sponsored insurance, traditional Medicare, or VA care if they so choose. It also preserves some private options in Medicare for those that want them. It’s an effort to capture the main benefits of single-payer — universal, guaranteed coverage alongside Medicare-based pricing — without taking away the insurance plans most people have and like. Bruenig was, to say the least, not happy with my description:

This is a good example of the slipperiness in the way Bruenig deploys this argument. Under Medicare Extra, there’s no churn on and off health insurance: it’s a universal program. If you chose to remain on your employer-sponsored insurance and then you got fired, you’d just be added to Medicare Extra.

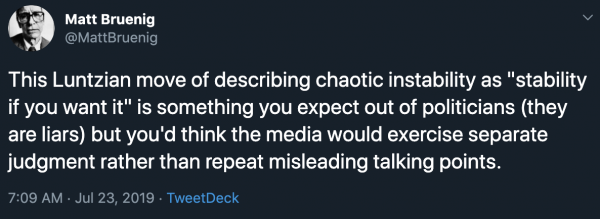

Bruenig’s claim that this is a lie rests on switching his definition to the first type of churn, the one that counts any change in plan. Under Medicare Extra, it’s true, you could end up switching from one employer-sponsored insurance plan to another, or from an employer who offered Cigna to one who bought into Medicare. Or you could choose to switch from Medicare to your employer’s insurance, or to the private options offered under Medicare Choice.

Bruenig says this would be “entirely out of your control.” That’s true in some cases, and not in others. Either way, Medicare-for-all is just as vulnerable to that critique: You can keep Bernie Sanders’s Medicare-for-all plan until the moment some other president and Congress decides to change the law. It’s also outside of your control. (And in a system where the White House and the Senate are both held by the party that won fewer votes, the idea that it is in your control because the government reflects the will of the people isn’t particularly convincing.)

This is the problem with the rhetorical game Medicare-for-all’s supporters are playing. If you narrow the definition of insurance churn to whether or not you have insurance, the argument doesn’t work as a cudgel against some of the competing plans like Medicare Extra. If you widen the definition of insurance churn to any change in your insurance plan, then it becomes a cudgel against Medicare-for-all too.

You can’t talk yourself out of public opposition

This gets to the broader context of this debate. There’s an effort among Medicare-for-all’s supporters to argue that nothing but pure single-payer can solve the problems of the health care system, and so any other plan, even if it’s more aligned with what the public wants, is an unacceptable half-measure. Since those plans make a virtue out of offering people more insurance choices, and since Medicare-for-all suffers in polls for abolishing private insurance, you need to make the offering of those choices into a weakness.

But in doing, you end up sidestepping the hard political question here, the one those other plans are trying to respond to: If the private insurance market is such a nightmare, why is the public so loath to abandon it? Why have past reformers so often been punished for trying to take away what people have and replace it with something better?

It’s simply not the case that when you say, in normal English, “if you like your X, you can keep it,” people believe you’re protecting them from all exigent circumstances. People live in the employer-based health insurance market now. They’re dealing with the instability Bruenig and others are pointing out as we speak. The fact that they’re not clamoring for the government to take it over demands exploration, not rebuttal.

Trying to redefine “it’s possible to lose the insurance you have now” as equivalent to “the government will take away the insurance you have now and move you to something different” isn’t a way of answering the concerns people have — it’s a way of trying to talk yourself out of answering them. And that’s a dangerous strategy.

It’s particularly unwise when the public’s views are as clear as they are here. A new Marist/NPR poll tested support for both “Medicare for all that want it — that is, allow all Americans to choose between a national health insurance program or their own private health insurance” and “Medicare for All — that is, a national health insurance program for all Americans that replaces private health insurance.” “Medicare for all that want it” polled at 71 percent. Medicare-for-all that replaces private insurance polled at 41 percent. Supermajority support becomes a minority position. Why?

There are different interpretations of what’s going on here. Many Americans simply don’t trust the government. Others don’t much like radical change, even if they do trust the government. Some reasonably want private options as escape hatches if the government option is wrecked by a future Congress, or marred by incompetent administration. Many don’t realize how much their insurance costs, because employers pay, on average, 70 percent of premiums, even if that quietly comes out of wages. And while about 60 percent of Americans think it’s the government’s responsibility to ensure everyone can access health care, that leaves 40 percent of the country that disagrees.

Indeed, the political risk of a plan like Medicare Extra isn’t that it changes too little for the public’s comfort, but that, like Medicare-for-all, it changes too much. Everyone on Medicaid gets forced into the new system. Everyone on Obamacare’s individual markets gets forced into the new system. The new plan will be better and more comprehensive than what came before it, so in theory, it should be a welcome change. But if “in theory, it should be a welcome change” always cashed out in practice, we would have fixed the health system long ago. The political upsides of Medicare Extra are that it won’t require as large tax increases, it won’t upend employer-based insurance, and it can at least claim that private choices will be available, but for all that, it will still mean huge disruption, far more than attended Obamacare.

For the record, I’m not opposed to Medicare-for-all. It’s one of many health systems that I think would be a vast, vast improvement on what we have now. I want more people to have better health care, and my fear is that in treating public opinion as infinitely malleable or simply confused, Medicare-for-all’s supporters will trigger a backlash that destroys the effort, just as so many health reformers have before them.

Risk aversion here is real, and it’s dangerous. Health reformers don’t tiptoe around it because they wouldn’t prefer to imagine bigger, more ambitious plans. They tiptoe around it because they have seen its power to destroy even modest plans. There may be a better strategy than that. I hope there is. But it starts with taking the public’s fear of dramatic change seriously, not trying to deny its power.

Further reading:

• The lessons of 1994. It’s been 25 years since the Clintons tried, and failed, to fundamentally restructure the American health care system. What went wrong then is worth studying.

• How to get to universal coverage without single-payer. How Medicare Extra works, and where it does and doesn’t differ from Medicare-for-all.

• 7 health care questions the 2020 Democrats should answer. I argue in this piece that centering the entire Democratic health reform debate on where or not you want to abolish private insurance is the wrong question. Here are some better ones.

Sourse: vox.com