Voters who skipped the midterms are different.

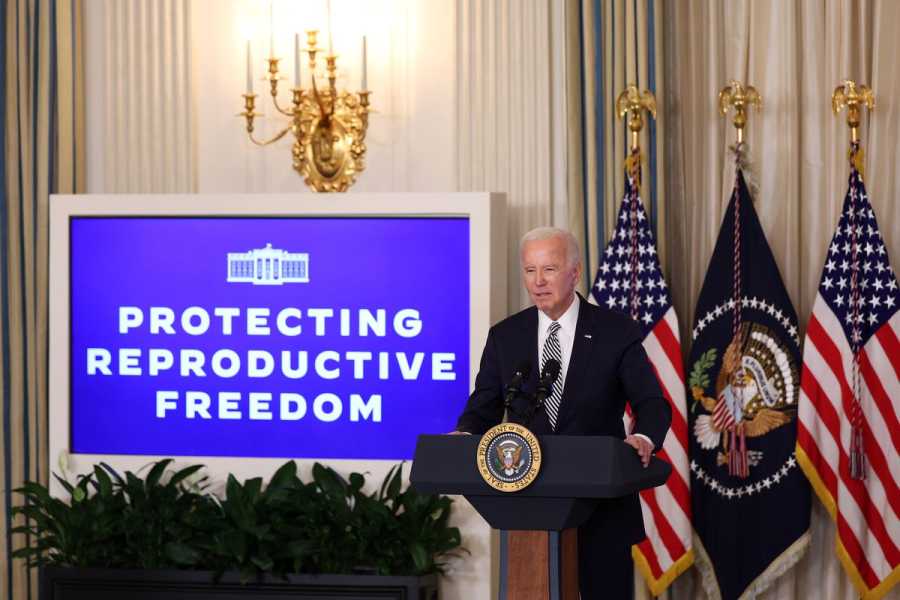

President Joe Biden delivers remarks during a meeting of the Reproductive Health Task Force at the White House on January 22, 2024. Kevin Dietsch/Getty Images Rachel M. Cohen is a senior reporter for Vox covering social policy. She focuses on housing, schools, homelessness, child care, and abortion rights, and has been reporting on these issues for more than a decade.

It’s no secret that Democrats are leaning hard into running on abortion rights for the 2024 cycle. Joe Biden has promised to bring back “the protections of Roe v. Wade in every state” and Congressional Democrats say abortion rights will be their top issue this coming year.

Democrats’ decision to center the overthrow of Roe is rooted largely in the massive success they’ve had running on abortion rights over the last two years, which helped them win a slew of special elections and outperform expectations in the 2022 midterms, staving off a red wave and keeping control of the US Senate. Pro-abortion ballot measures won in all seven states in which they appeared on the ballot since Dobbs, even in red states like Kentucky, Montana, and Kansas.

The party can point to critics who warned incorrectly that Democrats had erred in focusing so much on reproductive freedom, and public polling also underestimated the extent to which abortion rights motivated the midterm electorate.

Given this strategy’s success in the midterm and special elections, centering abortion rights seems like a safe bet for Biden in 2024. But the special circumstances of presidential elections — and the masses of voters they tend to attract — suggest this strategy is more of a gamble than it first appears.

Though abortion rights helped mobilize the kinds of voters likely to cast ballots in midterm and special elections, the presidential electorate generally looks different from those in off-cycle years. Roughly 160 million Americans cast ballots in the 2020 election, or 67 percent of the voting-eligible population. By contrast, just 112 million people voted in 2022, or 46 percent of those eligible.

Those who turn out every two years to vote — for primaries, midterms, presidential contests, and even special elections — are what scholars refer to as “high-propensity” voters. These people tend to be more highly educated and less diverse than those who only turn out once every four years.

So-called “low-propensity” voters, meanwhile, are generally not following politics closely and are less likely to have gone to college. They’re unlikely to be watching Fox News or MSNBC, probably not posting any Instagram stories about the Middle East or sending money to candidates. They are often less sure about what each party stands for, but they do generally turn out to vote, partly because voting is habitual, and for many it is seen as a civic duty. These particular voters (also referred to as “infrequent” voters or “less engaged” voters) have not yet turned out since 2020, or 18 months before the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade.

Polling indicates that it’s these voters that Biden is now struggling with, those who cast ballots for him four years ago but now are leaning toward Donald Trump or considering staying home on Election Day. Things have grown especially dire for the president among young, Black, and Hispanic low-propensity voters. Nate Cohn, the chief political analyst for the New York Times, said in October these less engaged voters “might just be the single biggest problem” facing Biden.

And for these voters in particular, abortion rights are simply not among the top issues they say they care about.

Low-propensity voters rank abortion low compared to other issues

First, the good news for Democrats: Low-propensity voters also support abortion rights. Broadly speaking, they even tend to identify as slightly more “pro-choice” than the rest of the electorate, according to Bryan Bennett, a pollster with the progressive polling firm Navigator. (Per Navigator’s data, infrequent voters are about 67 percent pro-choice and 27 percent anti-abortion, compared to the rest of the country that’s 64 percent pro-choice and 31 percent anti-abortion.)

But while low-propensity voters are largely pro-choice, they don’t rank abortion rights anywhere close to a top issue.

Among most voters — high-propensity and low — inflation and jobs top the list of issues they say are most important to them. Among low-propensity voters in particular, Bennett told me, jobs and inflation rank even higher than among the country overall. “So the high-level takeaway is that these are deeply economically focused folks,” he said.

Abortion access “just isn’t a top issue for infrequent voters,” Ali Mortell, the research director for the progressive polling shop Blue Rose Research, told me.

When Navigator asked low-propensity voters which issues they feel are most important for Congress to focus on, those voters ranked inflation and jobs highest, followed by health care (34 percent), then corruption in government, immigration, climate change, crime, Social Security and Medicare, and education all between 27 and 22 percent. Only after that did 17 percent of low-propensity voters rank abortion a top issue for Congress.

Meanwhile, among all voters likely to cast ballots in November, most don’t see Trump as a major threat to reproductive freedom. The progressive polling firm Data for Progress found in February that, while likely voters are “somewhat” or “very concerned” about restrictions on abortion rights, less than half see Trump specifically as a threat in that regard.

Only 48 percent think Trump will try to pass a national ban, and less than a quarter blame him for Roe’s demise, despite Trump himself taking credit for it. Perhaps most concerning for Democrats is that just 52 percent of respondents said they thought the 2024 election was “very important” to abortion rights.

What do voters who are abandoning Biden or waffling on him say they care most about? I asked Data for Progress if they could glean information about voters who cast ballots for Biden but are now saying they’re likely to vote for Trump in 2024. Per Vox’s request, they pooled about 12,000 survey responses from 10 national likely voter surveys they’ve run since the start of the year.

Danielle Deiseroth, executive director of Data for Progress, said their initial findings showed among likely Biden-to-Trump voters that the economy was their most commonly cited important issue. “Abortion almost ranked dead last in terms of issue importance, tied with race relations and education, and just ahead of LGBTQ+ issues,” Deiseroth added.

Abortion rights ballot measures underperformed with non-white voters

While pollsters agree abortion mattered in the 2022 midterms, it appeared to matter to varying degrees depending on whether you’re looking at state ballot measures or at contests for governorships to the US House and Senate.

Abortion rights ballot measures won in all seven states, largely because Republicans crossed the aisle to vote for them. Looking at the crosstabs, experts found that abortion ballot measures tended to over-perform with white Republican voters and underperform with non-white Democratic voters.

In Michigan for example, Gov. Gretchen Whitmer was much more popular with Black voters than the state’s winning abortion rights ballot measure. Likewise in Kentucky, the abortion rights ballot measure did well relative to partisanship in white suburbs and underperformed slightly in the major, Blacker metropolitan areas.

Abortion rights supporters cheer on August 2, 2022, in Overland Park, Kansas, as the proposed Kansas constitutional amendment removing the right to an abortion fails. Tammy Ljungblad/Kansas City Star/Tribune News Service via Getty Images

According to the New York Times, Biden appears to be struggling most with young, Black, and Hispanic working-class voters — those who identify as Democrats but did not turn out in 2022.

Abortion rights tend to rank lower for Black voters. These voters have become more liberal on abortion over time, but they are still more conservative on the issues relative to their partisanship, as the vote-splitting in Michigan indicated.

As Democrats campaign on abortion rights, they’ll have to be careful about how they talk about the issue. An Ipsos poll released in February on behalf of the abortion rights advocacy group All* Above All found that just under half of Black male respondents (48 percent) said they “personally supported a person’s right to abortion and believe it should be legal and available.”

If Democrats stick to language about fighting government interference in abortion decisions, however, they’ll be on safer ground. The poll found 43 percent of Black men said they were personally against abortion but didn’t believe the government should prevent others from deciding.

Still, only 17 percent of Black men said they’d only vote for a candidate who shares their view on abortion, and 38 percent said abortion rights were a small or nonexistent factor for them when determining their 2024 vote choice.

Voters are less likely to ticket-split in presidential contests as polarization ramps up

Biden and Democrats are making a political bet that women, who make up a slight majority of the electorate, will be particularly motivated to vote in November to protect abortion rights. Besides inspiring independents and first-time female voters, they hope some Republican women will cross the aisle, as they did in the midterms for abortion rights ballot measures.

“Clearly, those bragging about overturning Roe v. Wade have no clue about the power of women,” Biden declared in his recent State of the Union. “But they found out. When reproductive freedom was on the ballot, we won in 2022 and 2023. And we’ll win again in 2024.”

But this, too, is a gamble, as presidential contests tend to be much more polarized than off-cycle elections. The pull of partisanship is stronger; there is less ticket-splitting.

Recent focus groups with Trump-voting women in Pennsylvania found just one out of 15 participants said their feelings over the gutting of Roe v. Wade would drive them to vote for Biden in November. The Bulwark said while the women sounded like Biden voters on abortion rights, they also explained the issue didn’t carry the same weight for them as the economy or immigration.

“I’m going to vote for who I think is going to be the best for my family,” said one 35-year-old woman. Only one respondent worried a second Trump presidency could lead to a national abortion ban and a limit they did not support, like six weeks.

Why the abortion rights strategy could still work out

There are a few reasons why the abortion rights strategy could still pay off for the president in November, despite signs that the issue is not as resonant with the low-propensity voters he’s now trying to reach.

Mortell, the research director with Blue Rose, said their data shows that their top abortion messaging (around freedom from government interference and control) still resonates with lower-turnout voters and that it can be a powerful idea to leverage across all voter subgroups.

“It’s essential to talk about kitchen-table issues that voters care most about, not just abortion alone, but there’s no reason to exclude abortion in order to talk about those issues,” she told me. “In fact, during the 2022 midterms, we saw that some of the most effective ads used GOP positions on abortion to prove their extremism on other issues, like Social Security. It’s not the only issue, but it’s deeply interrelated with other personal freedoms and contextualizes each party’s values.”

During Biden’s State of the Union, he talked about other issues, leaning into messages that Republicans were beholden to the rich and that Democrats wanted to support the working class. More recently, Biden has gone after Trump about his comments on slashing Medicaid and Social Security.

Bennett, at Navigator, said he thinks it’s too early to know what the “issue landscape” will look like for voters by November, especially with the new attacks on IVF and the upcoming Supreme Court case attacking mifepristone. He noted that in recent national and battleground research they conducted, among the top issues and most intense concerns about both Donald Trump and Republican House Speaker Mike Johnson was their record on abortion.

Joey Teitelbaum, a pollster with Global Strategy Group who worked on the winning abortion rights ballot measure campaigns in Ohio, Colorado, Kansas, and Kentucky, told me that polls that ask voters to rank issues by importance often fail to capture how a respondent is truly weighing the topic in their mind.

“If the question is, ‘Do I personally think that I’m going to need to have an abortion in the next four years under a Trump presidency,’ that’s very different from, ‘Am I concerned about Republicans trying to control the decisions of my friends and family where they decide what’s best?’” she said. “These issue battery questions don’t capture that.”

Moreover, on low-propensity voters in particular, Teitelbaum noted there’s a big difference between not following the news closely and not knowing about what’s affecting your loved ones. “Voters might be low-information about campaigns and candidates but they’re high-information about what’s happening in their lives and their friends’ lives,” she said. “Those kinds of stories are not going to get lost.”

It’s also possible that the polls in 2024 are once again failing to capture abortion’s salience as an election issue. In 2022, public polls seemed to underestimate how much abortion rights ultimately mattered to midterm voters, and it’s becoming harder and harder for pollsters to get sufficient response rates to their questions.

“Poll after poll seemed to tell a clear story before the election: Voters were driven more by the economy, immigration, and crime than abortion and democracy,” Nate Cohn of the New York Times wrote last fall. “In the end, the final results … told a completely different story about the election.”

Another reason the strategy may still work is because by and large fewer than usual low-propensity voters may turn out in November this year, and there’s little doubt abortion rights remain a salient issue for high-propensity voters who lean Democratic.

As of now, fewer people seem to be following the 2024 election compared to the presidential primary in 2020, and as my colleague Eric Levitz recently wrote, the Republican Party also remains interested in various forms of voter suppression, even though polls suggest the GOP may be doing better with non-white voters now in particular. Thirteen red states enacted new voting restrictions in 2023, and Trump continues to rail against mail-in voting.

In the end, even if they don’t change their campaign focus, Democrats may benefit from their advantage with high-propensity voters. A Grinnell College survey from October found 2020 Trump voters were four points less likely to say they were definitely going to cast a ballot this year than 2020 Biden voters, and surveys from Marquette University found Biden performing better among likely voters than registered ones. Researchers I spoke with said they expect the president’s polling performance with college-educated voters and self-identified Democrats to improve as the campaign stretches on. If these voters turn out for the president, and overall turnout remains on the lower end, Biden has a better chance.

Sourse: vox.com