Recently, my mom sent me a text with a link to a story about a gang assault targeting a Jewish man in New York. “I’m worried for you,” she said.

I regularly wear a kippah, a traditional Jewish head covering. It’s people like me, Jews who anti-Semites can readily identify, who have been targeted by high-profile attacks in cities like New York and Los Angeles in the past few days — beaten while walking down the street, attacked while out to dinner, and even assailed by fireworks tossed out of a car.

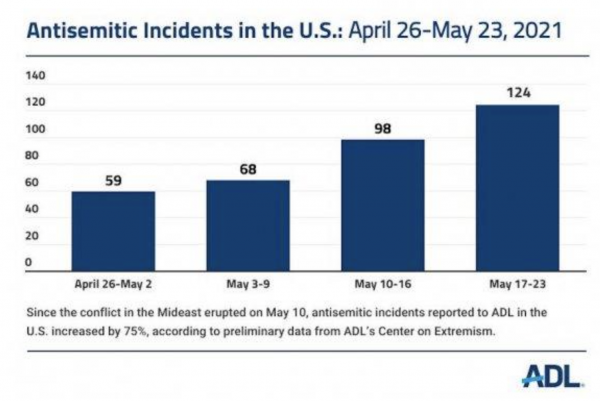

These attacks appear to be linked to the recent flare-up in fighting between Israel and the Palestinian militant group Hamas. In some cases, the perpetrators waved Palestinian flags or shouted pro-Palestinian slogans. The Anti-Defamation League (ADL), a Jewish civil rights group, found preliminary evidence that anti-Semitic incidents, ranging from harassment to vandalism to assault, increased by 75 percent during the recent conflict.

The ADL’s data has some problems: It might be overstating the current level of anti-Semitic animus. But the upsurge in anti-Semitic assaults linked to anti-Israel sentiment, in particular, seems new and different, and it is not something that typically happens in the US during fighting between Israel and Hamas.

“The violence … is one of the things that make this go-around a little bit different,” Oren Segal, the vice president of the ADL’s Center on Extremism, tells me.

What’s less clear is why these incidents are happening.

It’s entirely possible that it’s random chance, isolated incidents that mean little in the broader scheme of things. It’s also possible that the anti-Semitic attacks are part of the generalized surge in American anti-Semitism since 2016, which most experts link to the rise of Donald Trump and the alt-right movement. But perhaps the scariest possibility is that the US is becoming more like Europe, where anti-Semitic violence during military conflicts involving Israel routinely rises.

One thing, though, is clear: The American Jewish community is on edge. It’s a feeling that’s become sadly familiar since the 2018 attack on the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh.

Sign up for The Weeds newsletter

Vox’s German Lopez is here to guide you through the Biden administration’s unprecedented burst of policymaking. Sign up to receive our newsletter each Friday.

How real is the upsurge in anti-Semitic violence?

With any reported uptick in hate crimes, it’s important to start by asking whether the number of incidents has really increased or whether the crimes are simply getting more attention. Viral videos galvanize public outrage, but the data on the subject is notoriously difficult to compile accurately. Government data is spotty, and it can be very difficult to distinguish whether a crime that targets a member of a marginalized group is actually motivated by hate.

The ADL’s data is the most commonly cited non-government metric of anti-Semitism in the United States, often taken as authoritative. Its information is granular and swiftly updated, allowing researchers to separate out what was happening before and after the Israel-Hamas conflict began on May 10. By its numbers, there’s a clear break and rapid increase after the onset of hostilities.

But when you look under the hood, the numbers are a little bit more complicated. A recent article by Mari Cohen in Jewish Currents, a left-wing Jewish magazine, points out that the ADL’s tracker includes recent incidents that are only dubiously anti-Semitic — like a sign at a pro-Palestinian protest with the slogan “Zionism is racism. Abolish Israel.”

The expansive definition of what qualifies as an “anti-Semitic incident” is, as Cohen points out, a longstanding and well-known problem with the ADL’s data. In his book The Jewish-American Paradox, Harvard’s Robert Mnookin argues that the ADL “plays an important role in keeping both Jews and policymakers aware of the risks of anti-Semitism, both in American and worldwide, but often exaggerates those risks in language the mainstream media typically quotes verbatim.”

Yet even when put under a microscope, the current numbers are concerning.

Cohen redid part of the ADL’s math, looking at 43 recent cases in the ADL’s public tracker and excluding “incidents in which the ADL’s determination of antisemitism is controversial, including protest signs with anti-Zionist content or Holocaust comparisons.” Under her approach, there’s a drop in the overall number of incidents, but an even larger increase in percentage terms. While the ADL reports incidents increasing by 75 percent during the Israel-Hamas conflict, Cohen’s math suggests “more than a doubling.”

She also notes that the handful of violent incidents — the assault in Times Square, the beating of Jews out to dinner at a sushi restaurant in Los Angeles, Jews in Florida pelted with refuse, among a few others — are relatively new. “To my knowledge, we haven’t seen these attacks on Jews before during moments of mass protests on the street,” Ben Lorber, an analyst at the left-wing Political Research Associates think tank, tells Cohen.

During previous conflicts, the ADL has been deeply concerned by what it sees as anti-Semitic rhetoric at pro-Palestine protests. But this time around, Segal tells me, the language at these events has been relatively measured.

“We haven’t seen the massive amount of anti-Semitism at these rallies as we’ve seen in the past,” he says. “There is a toning down of most protests … that, in the past, would be overwhelmed by inflammatory messages.”

This suggests that the ADL’s current numbers aren’t merely a reflection of an overly expansive definition of anti-Semitism. But it also poses a difficult question: Despite the toned-down rhetoric at mass rallies, why does there appear to be a link between the conflict in Israel and the anti-Semitic violence in America?

In LA, the attackers — who drove to a specifically Jewish neighborhood to find Jews to hurt — were flying Palestinian flags. In Times Square, the violence grew out of a pro-Palestinian protest. In Florida, the attackers yelled, “‘Free Palestine, fuck you Jew, die Jew.”

This isn’t normal. Something new appears to be happening, but it’s not yet clear what it is.

Three theories as to why there’s a sudden surge in anti-Semitism

Because we’re less than two weeks removed from the ceasefire between Israel and Hamas, it’s very hard to draw clear conclusions as to why anti-Semitism spiked in America during the fighting. We can’t even be sure the wave of anti-Semitism has crested — it’s possible things will get worse rather than better.

But here are three different hypotheses, none of which are proven, but each plausible and consistent with the information we have so far.

The first theory is also the simplest: These are isolated incidents and not reflective of any deeper trend.

The number of violent assaults targeting Jews every year is very small, in the dozens rather than hundreds. When your sample size is that small, a few incidents can take on outsize importance. The attackers may have claimed to be acting on behalf of the Palestinian cause, but ultimately, there may be no systematic reason to think that the increase in public pro-Palestinian sentiment is in any way linked to anti-Semitic violence.

This is, more or less, Cohen’s conclusion in her Jewish Currents piece. “Given an American Jewish population of 7.6 million, [this is] hardly an epidemic,” she writes. “The ADL’s narrative also serves to reinforce lurking anxieties that advocacy for Palestinian rights is inherently antisemitic — even as Palestinian leaders have condemned antisemitism publicly and repeatedly.”

A second theory is that what we’re seeing right now is, more than anything else, a reflection of an upswing in anti-Semitism that began during the Trump campaign and presidency.

There is little doubt that anti-Semitic sentiment in America began spiking in 2016. The ADL and other data sources suggest a surge beginning then, most commonly linked to the alt-right’s rise on Trump’s coattails, and continuing for the next four years. The violence has been severe.

In October 2018, a far-right gunman killed 11 people at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh — the deadliest anti-Semitic attack in US history. In April 2019, another anti-Semitic shooter targeted the Chabad synagogue in Poway, California, killing one. In December 2019, amid a wave of assaults targeting visibly Jewish men in Brooklyn, a man wielding a machete attacked a Hanukkah party in the New York suburbs, killing one and injuring four.

In a 2021 paper, scholars Eitan Hersh and Laura Royden tried to isolate what kinds of people, exactly, were attracted to anti-Semitic ideas in modern America. They found that three groups — white conservatives, Black Americans, and Latinos — were disproportionately likely to agree with anti-Semitic statements like “Jews have too much power in America.” Among Black and Latino people, those who self-identified as conservative politically were also more likely to display anti-Semitic attitudes. Anti-Semitism was generally higher among younger Americans than older ones.

The connection between anti-Semitism and pro-Palestinian sentiment in Hersh and Royden’s data is tenuous at best. Among those who said Jews had too much power in America, only a small percentage pointed to Israel-Palestine as the area where they wield this malign influence — suggesting to Hersh and Royden “that support for these statements is not closely connected to the Israel/Palestine conflict.”

At the same time, anti-Semitism tends to travel across the fringes of the political spectrum. It’s possible the explosion in online anti-Semitic expressions from white nationalists, for example, influenced a small subsection of Palestinian sympathizers. This tracks with the age demographics in Hersh and Royden’s study — younger people get more of their information online.

“A huge difference between now and [the Israel-Hamas war in 2014] is the online environment,” Segal says. “Despite the constant concerns raised about anti-Semitism and bigotry of all kinds and extremism on these platforms, we saw an explosion of anti-Semitism … which further normalizes anti-Semitism.”

Third, it’s possible we’re seeing the beginning of what might be termed the “Europeanization” of American anti-Semitism.

While upswings of violent anti-Semitism during Israeli-Palestinian conflicts are relatively rare in the United States, they’re common in Western Europe. Data from the Kantor Center at Tel Aviv University shows that, during the 2008-’09 Gaza war, there was a massive spike in anti-Semitic violence, death threats, and vandalism worldwide — with a high percentage concentrated in European countries with sizable Jewish populations like France. During the current conflict, early data from the United Kingdom showed a 600 percent increase in anti-Semitic incidents.

The link between anti-Israel and anti-Semitic attitudes in Europe is fairly well established. A 2006 study by Yale’s Edward Kaplan and Charles Small found that, in a survey of 500 Europeans, “anti-Israel sentiment consistently predicts the probability that an individual is anti-Semitic, with the likelihood of measured anti-Semitism increasing with the extent of anti-Israel sentiment observed.”

It’s possible this connection is deepening in the United States, that people with anti-Israel views are increasingly more likely to blame American Jews for what they see as Israeli wrongdoing and are more likely to inflict physical violence upon them as a result.

But one salient difference between the United States and Europe is the status of Muslims.

Many of the perpetrators of anti-Semitic violence in places like France are from alienated and socially marginalized Muslim communities. American Muslims by contrast, tend to be more tightly integrated into American society. Moreover, American Muslims and Jews tend to have positive views of each other despite disagreements on Israel-Palestine. For these reasons, communal violence during Middle East flare-ups is much rarer in America.

“In parts of Europe where you have bigger Muslim populations, you have this,” Hersh tells me. “But we haven’t seen that kind of violence in places [in the US] with bigger Muslim populations.”

The identities of many of the recent attackers in the US right now have not been confirmed. Though the names of at least four people arrested in conjunction with the New York and Los Angeles disturbances have been released, it’s difficult to draw firm conclusions about how and why they got involved in the violence until more information is made public.

But the fact that some of these incidents seem directly tied to pro-Palestinian events and sentiment, with little or no connection to the far-right factions that traditionally commit the most serious anti-Semitic violence in the United States, presents troubling data points. It’s possible, if not likely, that the European pattern of violence in Israel causing anti-Semitic violence at home could become a reality in America.

It’s far from clear which, if any, of the three explanations presented above will turn out to be the correct one. And they aren’t necessarily mutually exclusive.

But what’s clear now is the Jewish community is once again confronting the fact that anti-Semitism is alive and well in America. A Pew survey of American Jews, conducted in 2020 and released in May, found that three-quarters of American Jews believed there was “more anti-Semitism in America than there was five years ago.” Fifty-three percent said they feel personally less safe as a result.

The current wave of violence will do nothing to assuage my agitated community — one with very good historical reasons to fear for our safety.

Will you support Vox’s explanatory journalism?

Millions turn to Vox to understand what’s happening in the news. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower through understanding. Financial contributions from our readers are a critical part of supporting our resource-intensive work and help us keep our journalism free for all. Please consider making a contribution to Vox today from as little as $3.

Sourse: vox.com