The best works of history are always the ones that illuminate the present as much as the past.

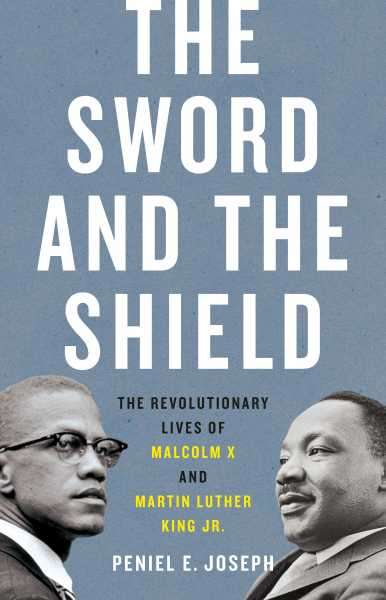

A new book by Peniel Joseph, a historian at the University of Texas, is the latest addition to this genre. It’s called The Sword and the Shield, and it’s a dual biography of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. A lot of books have been written on both of these men, but Joseph’s book is different in that it’s much more about the dynamic between Malcolm and Martin than it is about their individual stories.

And that complicated dynamic is worth revisiting in light of the social unrest after the killing of George Floyd. So I spoke with Joseph for Future Perfect’s limited-series podcast, The Way Through, which is all about exploring the world’s greatest philosophical and spiritual traditions for guidance during these difficult times.

This is a conversation about how these two figures defined and shaped the struggle for racial justice in America. In that sense, it’s very much a conversation about the present told through the prism of the past.

But this is also an exploration of the political philosophies of Malcolm X and MLK and why they’re not nearly as antithetical as we’re made to believe. In the end, as Joseph explains, Malcolm and Martin speak to the eternal tension between reform and revolution, idealism and pragmatism. But their story also shows that the choice between these approaches isn’t always so clear — and sometimes isn’t really a choice at all.

You can hear our entire conversation in the podcast here. A transcript of our conversation, edited for length and clarity, follows.

Subscribe to Future Perfect: The Way Through on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher or wherever you listen to podcasts.

Sean Illing

Your book is very much about debunking two-dimensional myths around Martin Luther King Jr. as a safe, comfortable insider and Malcolm X as the by-any-means-necessary renegade. There’s obviously some truth in those caricatures, but what do they miss?

Peniel Joseph

I like that you said “safe,” Sean. So I’ll start with Dr. King, because Dr. King is anything but safe.

One of the pleasures of doing the research and writing the book was seeing and really being in awe of how bold Martin Luther King Jr. was and how much love he had for political underdogs of all stripes. One of the things that people miss is that Dr. King is a revolutionary, somebody who is really leading the whole United States of America and the whole world toward this moral and political reckoning that accelerates during the last three years of his life.

But what’s also missed is the way in which Malcolm X, who is the boldest critic of white supremacy of his generation and really of the 20th century, becomes King’s alter ego and absolutely impacts King’s radicalism, King’s ability to work with Black Power icons and revolutionaries like Stokely Carmichael.

I think the interesting part about doing this research was that I always imagined what if there was a book about King and Malcolm X that looked at each comparatively in their own time. So you get King and Malcolm in the early ’50s alongside each other, and when you look at their public careers (for King it’s 1955 to 1968 and for Malcolm it’s 1952 to 1965), you see not just juxtapositions but real convergences.

Sean Illing

What’s interesting to me, especially in this moment, is the tension between idealism and pragmatism, or between moderation and extremism, or between reform and revolution. These are never truly binary choices — it’s always a question of maintaining the right balance and knowing what’s needed and when.

Peniel Joseph

Absolutely. I think that Malcolm X is a great example of somebody who in a lot of ways is a radical pragmatist. He’s somebody who wants to get free of colonialism, free of anti-Black racism. And when he says “by any means necessary,” people take that as a threat, but really it’s consonant with the Black freedom struggle. Because when we think about the Black freedom struggle as a multiple-choice test, the answer is always D, all of the above. The answer is people want self-determination and liberal integration.

People want protection from racism, but they also want the right to choose what tactics and strategies they’re going to use. Some people are both self-defense advocates and advocates of nonviolence simultaneously. We had Black women, Black feminists join the Black Panthers and push back against the patriarchal and toxic masculinity that at times the Panthers embraced.

So people can hold competing thoughts in their own minds constantly. When we think about Malcolm and Martin, they are both revolutionaries, but along that evolution, at times they are very pragmatic, at times they are moderates.

One of the things I write about Malcolm is that Malcolm is Black America’s prosecuting attorney, but he becomes the statesman. And Dr. King is the defense attorney who becomes this pillar of fire. He becomes this man on fire in the last several years of his life, and he’s prosecuting and castigating in a way that we never think about King.

Sean Illing

That’s one of the most fascinating things about MLK’s legacy. There’s so much more than the “I Have a Dream” speech. As you say, MLK is actually quite radical, but his radicalism is cloaked in a theory of moderate change, which I think speaks to his political genius in a lot of ways.

Peniel Joseph

I like the word you use, “cloaked,” because in a lot of ways even the “I Have a Dream” speech is a radical speech. He starts that speech by saying, “Now is the time to make real the promise of democracy.”

And this is August 28, 1963, he’s speaking before a quarter of a million Americans, 90,000 of them are white. And in that speech, he says, “Today we come to cash a check, a check that has been stamped ‘insufficient funds,’ but we refuse to believe that the great vaults of opportunity in America are bankrupt.” One of the things I argue is that both Malcolm and Martin had their own 1619 projects.

Sean Illing

Do you think that, perhaps because of the way Martin couched his radicalism, a lot of people who don’t share his vision have exploited it or co-opted it in ways that portray it?

Peniel Joseph

Dr. King was assassinated Thursday, April 4, at 6 pm, Memphis time, in 1968. And the whole country is at a crossroads.

This is just two months after the Kerner Commission report is published. That commission is a bestseller with over 650,000 copies that year. And that commission says that the nation is turning into two separate nations — white, Black, separate, unequal, and hostile — and that the ghetto has been created and is a creation of white people and white supremacy, of white politicians, and the only way out of the racial maelstrom of the 1960s is for us to have a massive investment in Black communities and racial desegregation.

And instead, we choose law and order. And so when we think about what activists led by Coretta Scott King and people like Vincent Harding, people who were very close to Dr. King, faced a choice about how to institutionalize the memory of this activist and in so doing institutionalize the memory of the civil rights movement.

And they successfully did so. It took 15 years from the day of MLK’s death to the day President Ronald Reagan signed the MLK holiday into law. That’s extraordinary. That absolutely could not happen now. Reagan was not a friend of the Black freedom struggle, he was not a friend of the Black Panthers, he was not a friend of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. He was compelled to sign that law.

But it happens because the movement successfully convinces enough white politicians that Dr. King’s legacy is an example of the beauty of American exceptionalism. That’s the choice. And so sometimes people say, “Well, what happened to King’s legacy?” That was the choice. The only way to get King enshrined in the memory of Americans and American democracy was to say he exemplifies why we are so special.

Sean Illing

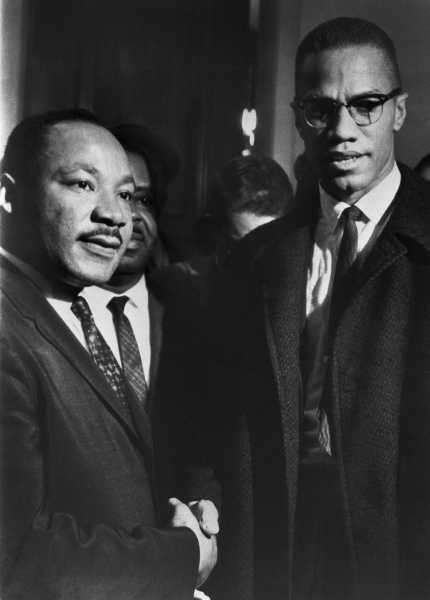

I want to ask about the relationship between Malcolm and Martin, which was deeply complicated and pretty ugly in the beginning. While preparing for this conversation, I went back and watched old interviews of Malcolm X, and I was surprised at how ruthlessly he attacked Martin. He called him a “religious Uncle Tom” and said he was “subsidized by the white man to keep Black people defenseless.” These are strong words, and yet the dynamic between them continually evolved in a common direction.

Peniel Joseph

This is an important time to talk about Malcolm’s and Martin’s origins. Malcolm is born on May 19, 1925, in Omaha, Nebraska, to two Black activists, Louise and Earl Little. His mother is from the Caribbean from Grenada, his father is from Georgia.

And Malcolm X’s parents are Garveyites. Marcus Garvey is the Black nationalist revolutionary pan-Africanist who organizes the Universal Negro Improvement Association, which is the largest mass Black freedom movement in world history. Malcolm is coming from that tradition, but it’s also a tradition of racial trauma. His father is murdered by white supremacists when he’s 6 years old in Lansing, Michigan. His mother is institutionalized in a psychiatric hospital for most of his adult life.

Malcolm Little, as he was called at birth, is a foster child until he moves to Boston at the age of 15. He’s over 6 feet tall at the age of 15. He moves to Boston to live with his half-sister Ella Mae Collins. And for the next six years, Malcolm is operating at the lower frequencies of Black life in Roxbury, Boston, and in Harlem, selling marijuana. He’s connected to all kinds of illegal activities. He’s at times working as a day laborer, he’s working as a cook, he’s working as a Pullman car porter. Finally arrested in 1946, he spends 76 months in prison for theft, being part of an interracial theft ring in Massachusetts.

Martin Luther King Jr., who was born January 15, 1929, in Atlanta, is a young Black prince. He’s the son of one of the most important preachers in Georgia, at Ebenezer Baptist Church. Martin King’s father is coming from sharecroppers, Martin King’s mother is coming from Black people who were very successful entrepreneurs and preachers. And so that’s how he grows up. He goes to Morehouse College at 15. When he is in his sophomore year at Morehouse College, Malcolm, who is three and a half years older, is being called Satan because of his attitude in prison.

So these are two African American political leaders whose understanding of American democracy, whose understanding of race, is shaped by their own experiences. Malcolm in prison joins the Nation of Islam, has his epiphany in prison, and really becomes even more than just a political activist. He becomes an intellectual in prison, a scholar in prison, and uses that time to hone debate skills, to read about religion, African history, African American history, Du Bois, the whole range of the Black freedom struggle. King is getting this under the tutelage of people like Benjamin Mays, the president of Morehouse College.

So when we think about King, King’s vision of American democracy, even as he imbibes, he’s reading Gandhi, he’s reading Howard Thurman, he’s reading the theologian Paul Tillich, he’s reading philosophers, he’s reading Marx, his understanding of Black and racial oppression is at the abstract level, even though he’s experienced some racism.

Sean Illing

One important thing they did agree on is that America had two systems of violence. White violence against Black bodies was necessary, legal, justified, and Black violence, even in defense of Black dignity was criminal, dangerous, subversive. And it’s revealing and depressing that all these years later, despite all the progress that’s been made, we’re still having this conversation today.

Peniel Joseph

Yeah, and they both really do have meditations on violence and democracy, but Malcolm absolutely preaches this idea of self-defense and this idea that Black people have a right to defend their bodies. I think one of the mythologies about Malcolm X is that he’s somehow preaching guerrilla warfare against white people. Even though at times he predicts race war, his predictions are based on anti-Black violence. They’re actually based on white racial violence that is coming both from ordinary white citizens, but also from law enforcement and state-sanctioned violence against Black communities.

So Malcolm understood the history of Tulsa, Oklahoma, and the racial pogroms that had happened. His family had been victims of one such act of violence. Earl Little had been viciously murdered. And so when you think about Malcolm, Malcolm’s notion of violence is that Black people absolutely have the right to defend themselves. And he’s very critical of King for putting Black people in harm’s way in Birmingham, Alabama, for putting Black people in harm’s way where German shepherds are attacking them. Malcolm famously says that Black people have the right to defend themselves and kill two-legged or four-legged dogs that are attacking them.

And this is one of the interesting things about Malcolm with violence: He constantly leaves interviewers and debaters silent when he says that he’s not against racial integration. Because they say, “Well, what do you mean? The Nation of Islam, racial separatism? What do you mean?” He says that, “If we didn’t have to march, if we didn’t have to protest, if we didn’t have to sue for racial integration, I’d be fine with it.”

He’s actually right. There was no need. Without white supremacy being sort of this foundational part of the United States, there is really no need to have some kind of civil rights movement.

The Brown [v. Board of Education Supreme Court] decision after 1954 means that there should be no more protests about racially integrating schools, but there are, and Malcolm is saying, “If you live in that kind of society, you should choose separation. And separation means that Black people themselves are deciding what kind of lives they want to live.” And he says separation is different from segregation because it’s Black people realizing that the United States is what Dr. King said it was: a sick society suffering from the cancer of racism.

“Malcolm is Black America’s prosecuting attorney, but he becomes the statesman. And Dr. King is the defense attorney who becomes this pillar of fire.”

Sean Illing

The movement for racial equality today intersects with the legacy of Malcolm and Martin in important ways. As you say in the book, there are the large-scale acts of disobedience that echo MLK and the defiant rejections of America’s systemic racism that echo Malcolm. If they were alive today, what do you think they’d say? What do you think they’d do?

Peniel Joseph

I think they would have a lot to learn from these current movements, especially the intersectional aspects of identity in terms of race, class, gender, sexuality, and how that has been so central to these movements in really beautiful ways. I think that they would both be supportive of the BLM movement and be trying to work at it in different ways.

When we look at Malcolm, he was really interested in the global stage. He was interested in setting up coalitions and alliances in Africa, the Middle East. He’s at Oxford University in one of his last speeches where, very famously, he’s taking the Barry Goldwater side for different reasons of extremism in defense of liberty is no vice. And he’s saying at the end of that speech that he’s willing to get together with anyone, no matter what color, who wants to change the miserable condition on the face of this earth. So I think Malcolm would really be interested in these global demonstrations, be interested in how can we transform Africa and the Middle East.

And I think King would be doing what he did in 1968. King was trying to lead a multiracial army of the poor. When you think about the Poor People’s Campaign alongside of Marian Wright Edelman, the head of the Children’s Defense Fund, he was getting together with Native American and Indigenous Latinx farm workers, whites from Appalachia, and other places alongside of Black people to get what we now call a universal basic income. King argued for guaranteed health care, and he talked about food justice and environmental health care, and so he was very interested in what we’d now call intersectional justice.

So when we think about where they would be, they’d be doing the whole notion of radical Black citizenship and dignity, but at the global scale. King was absolutely interested in how do we change democratic institutions from within. And I think Malcolm really wanted to apply pressure against American imperialism.

Sean Illing

Your book really does capture the wonderful complexity of this relationship. On the one hand, Malcolm’s “sword,” as you call it, is a means to mobilizing Black consciousness, and Martin’s “shield” is a means of capturing the centers of American power and forcing it to bend to the demands of justice and to recognize Black citizenship.

Peniel Joseph

And they really both held it because King holds [the sword] at the end and Malcolm by ’64 is taking that shield that he learned from King, and he’s trying to bring that diplomatic shield to form coalitions with civil rights activists and also in the Middle East and the Third World and in Africa and Europe. Malcolm is planning to go to the United Nations and charge the United States with crimes and human rights violations against Black people.

And King, near the end of his life, is talking about militarism and materialism and racism, and he spends a whole year in Chicago and he’s using both the political sword and the political shield. He even writes in 1965 beyond the Los Angeles riots that he’s going to use nonviolent civil disobedience as a massive political shield in service of racial and economic justice.

In his final speech on April 3, 1968, King is beyond the “I Have a Dream” speech, and he’s much more defiant. He says, “In Birmingham, we didn’t let any German shepherds or fire hoses turn us around,” and he says, “Tomorrow, we’re going to march and we’re not going to let any illegal injunction turn us around.” King right there, that final evening, he’s saying that nonviolent civil disobedience answers to a higher calling. He’s saying we’re going to march with these 1,100 striking sanitation workers in Memphis, Tennessee, for a living wage, no matter what courts tell us, no matter what police tell us.

This is Martin Luther King Jr. When you see this, you say, “Oh, my God. This is extraordinary. This is what Malcolm had been asking and demanding in ’63 when Malcolm X said the March on Washington was a farce on Washington.” Malcolm said they should have paralyzed the entire city. That we needed a reckoning. We didn’t need to wait. And what King by the late ’60s says is, “Yes. We’re going to use nonviolent, political, civil disobedience as a political sword and a shield.”

So it becomes clear when we read and we study King and we ask, “Why was he assassinated?” This is a man who represented global political mobilization, and he had the moral power of the entire world behind him. If King had stayed in Washington, DC, in the summer of ’68, the election, this country would have been transformed — that I guarantee.

Will you become our 20,000th supporter? When the economy took a downturn in the spring and we started asking readers for financial contributions, we weren’t sure how it would go. Today, we’re humbled to say that nearly 20,000 people have chipped in. The reason is both lovely and surprising: Readers told us that they contribute both because they value explanation and because they value that other people can access it, too. We have always believed that explanatory journalism is vital for a functioning democracy. That’s never been more important than today, during a public health crisis, racial justice protests, a recession, and a presidential election. But our distinctive explanatory journalism is expensive, and advertising alone won’t let us keep creating it at the quality and volume this moment requires. Your financial contribution will not constitute a donation, but it will help keep Vox free for all. Contribute today from as little as $3.

Sourse: vox.com