Health care monopolies have helped make America’s medical costs the highest in the world. Incoming US Health and Human Services Secretary Xavier Becerra faced that problem head on when he was California’s attorney general.

In that role, Becerra oversaw one of the largest health care antitrust settlements in US history, targeting a San Francisco hospital system that had bought up its competitors and allegedly used manipulative contracting practices to gobble up more and more health care business in the Bay Area.

This consolidation is happening all over America. Hospitals have been merging with one another and buying up physician practices; health insurers have been consolidating as well. The strong consensus of researchers is that this market consolidation leads to higher prices and lower quality for US patients. Fighting it is one way President Joe Biden could deliver on his promise to lower health care costs and improve access for Americans.

Antitrust enforcement is not the sexy version of health care reform. It’s certainly not Medicare-for-all, which would put all Americans on one government health insurance plan, then use the enormous leverage such a plan would have to set lower prices and eliminate cost-sharing for patients. It’s not even the public option, as proposed by Biden during his campaign, which would introduce a cheaper government health plan to compete with private insurers.

But it can help prevent providers from inflating the prices they charge health insurers, which inevitably pass along those costs to patients in the form of higher premiums.

It also might be more feasible. A 50-50 Senate will limit how ambitious Biden’s legislative agenda can be. But antitrust action can be undertaken without Congress, though Congress could do more to support it. And while Becerra himself wouldn’t be able to lead the charge, there are steps his agency could take to reduce the incentives for health care providers to consolidate. The Federal Trade Commission could be emboldened to act more aggressively to intervene if new health care mergers threaten competition.

Trust-busting is not a cure for all the ills that afflict American health care. One expert compared it to a game of whack-a-mole: if you’ve cracked down on one monopoly, then you’ve cracked down on one monopoly. Another one is bound to pop up somewhere else.

But it’s better than nothing.

The problem: Health care monopolies increase costs for everybody

US health care relies on markets. Almost all health care providers, both doctors and hospitals, are private. More than half of health care is privately financed. The feds and state governments play an important role in setting the rules of the road, and in paying for much of the medical care Americans receive, but the country’s health system depends on competition to deliver care to people and to restrain costs.

This is how it’s supposed to work: Health insurers enroll people into their coverage plans. The insurers negotiate with the hospitals and doctors in their area to provide services to the patients who pay for their insurance plans. Health insurers are supposed to have certain tools to gain leverage in those talks so they can negotiate lower prices. For example, they might put one doctor or hospital in a “preferred” category, and the plan then charges patients less than they would pay for a non-preferred provider. That should, in theory, prompt the providers to offer services at lower cost or higher quality (or both).

The problem is that, in practice, this system hasn’t been working very well, and monopolies are a big reason why. They swing the balance of power from the consumers to the providers. The example of Sutter Health, a Bay Area health system that Becerra filed an antitrust lawsuit against as state attorney general, is illustrative.

According to the complaint from Becerra’s office, Sutter Health had contrived to buy up many of its competitors and consolidate its power in Northern California. Its system grew to encompass two dozen hospitals and 35 outpatient health clinics; Sutter employed or partnered with more than 17,000 doctors across the region.

It used that enormous market share to its advantage. According to the complaint, the health system required insurers to include all Sutter facilities in their networks; it made demands that its providers must be included in preferred tiers; and it set high prices for any out-of-network services that it might provide.

The message was clear: Either include our facilities in your plan’s network, with preferred status, or your patients risk facing huge medical bills if they try to get medical care at any Sutter Health location. With so few alternatives available, because Sutter had bought most of them, that was not palatable for a health insurer that wanted to stay in business. So they were forced to come to the negotiating table with the Sutter Health system.

“Just the threat of not entering into a contract is coercive,” Kristof Stremikis, director of market analysis at the California Health Care Foundation, says. “That’s leverage and that’s a very dangerous potential blank check.”

One analysis of facilities formerly owned by Summit Medical Center, acquired by Sutter in 2000, found prices had increased between 28 and 44 percent after their merger.

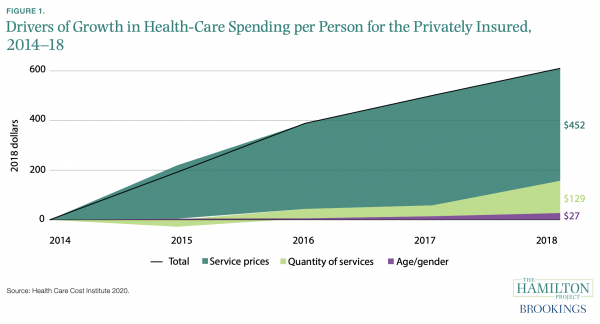

We don’t know exactly how widespread these contracting practices are. But we do know that the conditions are ripe for anti-competitive contracting in many places — and we also know that higher prices, which providers can negotiate under these circumstances, account for most of the health care spending growth seen over the last decade.

According to economist Martin Gaynor at Carnegie Mellon, who authored a paper last year on how health care markets could be made more efficient, the average hospital market in the US is considered “highly concentrated” according to the criteria used by federal agencies. So is the average market for specialist physicians and health insurers. Primary care doctors just barely miss the cut, but it’s close.

This consolidation is actually worst outside of major metropolitan areas. According to a 2019 Health Care Cost Institute report, the three most concentrated hospital markets in the country are in Springfield, Missouri; Peoria, Illinois; and Cape Coral, Florida. Some of the other cities in the top 10 were Albuquerque, New Mexico; Reno, Nevada; and Omaha, Nebraska.

“Something I would be concerned about is so many geographic areas in the US are dominated by one really big health system. They don’t want more competition,” Gaynor says. “If you’re a firm and you’ve merged or acquired to dominate the market, you want to maintain that position, enhance it if you can.”

These monopolies give providers power to negotiate higher prices from health insurers, and most of the US’s recent cost growth has been driven by increases in the prices charged for medical services, rather than the quantity of services used.

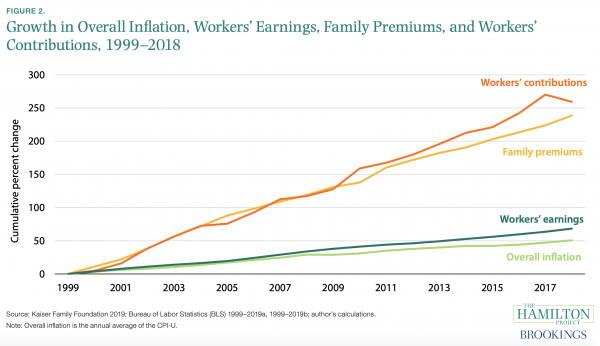

Patients rarely have to pay the full cost of medical care so long as they are insured. But, one way or another, everybody pays for high prices. If insurers are forced to pay more money for care because there’s only one hospital system in their area, they are going to pass along the costs in the form of higher premiums or fewer benefits.

Over the last 20 years, American workers have been asked to pay more and more of their own money for health insurance. The health care costs for workers have risen much more quickly than their wages.

Medical monopolies cost everybody. But what can be done about them?

One solution to high health care costs: More antitrust enforcement

The settlement that Becerra, as California attorney general, reached with Sutter Health in 2019 provides an example of how aggressive enforcement can constrain anti-competitive practices and, hopefully, keep costs for patients more in check.

Sutter made a $575 million payment to large employers and unions, the customers of the health insurers over whom Sutter had wielded so much leverage because of its market share. The health system also agreed — without, technically, admitting wrongdoing — not to use certain contracting practices. The company cannot require health insurers to put its facilities in a “preferred” tier, or require they include all Sutter facilities in their network. Sutter also agreed to limits on how much it could charge for out-of-network care.

The Biden administration could follow Becerra’s lead by flexing its enforcement muscles and trying to win more settlements like this in places where health care monopolies have led to egregious anti-competitive practices. Some mergers occur across state lines. But there are also precedents for the federal government teaming up with states to pursue antitrust actions, such as the case brought against Atrium Health in North Carolina, which was settled with the same kind of ban on anticompetitive contracting as in the Sutter settlement.

Experts like Gaynor hope the feds will be aggressive under Biden — and they believe Congress could take small steps to give the government more power to intervene when the market is failing.

Some of it is just a matter of money. Given the number of mergers occurring and the flat funding for antitrust agencies over the last 10 years, Gaynor estimated the Department of Justice and FTC need about $150 million to adequately fund those activities, an amount that he describes as “a drop in the bucket of the federal budget.”

“If we’re serious about antitrust enforcement,” he says, “then the agencies need substantial increases to their budgets.”

Congress could also give the FTC, which has historically overseen the hospital and physician markets, more authority to take action. The agency is currently prohibited from taking action against nonprofit businesses, a category that includes many hospitals; Congress could change that law. Many smaller mergers, which could include physician practices, are not required to report their transactions to the feds; lawmakers could also pass a bill that would mandate such

Becerra himself actually won’t have much of an antitrust role as health secretary. But his department could also take some steps that would reduce incentives for health providers to consolidate.

One example, from Gaynor: Currently, Medicare will pay a surcharge for medical care provided at a hospital, even if the same service could have been given in a non-hospital setting. So if hospitals employ more physicians, or if physicians are acquired by a hospital, they receive this financial benefit when providing those services. Medicare could revise its payments to be “site neutral,” so the cost is the same no matter where the care is provided.

In general, HHS could make analyzing the competitive effects of its rules and regulations part of the review process. It could explore ways to prevent data blocking between health systems, too. There is not a standardized electronic medical record system in the US, and records often can’t be shared across different systems.

Antitrust enforcement isn’t a replacement for more aggressive reforms

The Biden administration has a lot of tools in its antitrust toolbox, and Congress could unlock a few more by expanding the FTC’s authority and budget. But experts also caution that there are limits to what health care trust-busting can achieve.

To take the example of Sutter: While the company has accepted some constraints in how much it can leverage its market power to exact higher prices, it is still the dominant health system in the Bay Area. It just has to behave a little better now.

“This [settlement] does not change the degree of consolidation in the health care system in California,” Stremikis said. “There’s consolidation everywhere. That train has left the station and you can’t pull it back.”

Antitrust enforcement is usually slow (it took nearly 10 years for the Sutter case to be resolved) and it’s by nature surgical (every individual monopoly gets targeted with its own enforcement case). A more aggressive federal government can make examples out of bad actors, but in order to get costs under control across the country, more sweeping reforms are probably needed.

But big changes to US health care are hard. Single-payer health care is off the table for the time being. Even rate-setting, like the kind seen in Maryland, may be too aggressive for the more moderate members of the Democratic Senate majority, especially because the health care industry is sure to mobilize against such a proposal.

Nobody is talking about shiny new health care cost controls in the middle of a pandemic when health care workers have been hammered. Even Sutter asked California to revisit its settlement terms to consider the financial losses the system has taken because of Covid-19.

But medical monopolies aren’t going away. They are a structural problem driving the nation’s health care affordability crisis. If Biden is serious about doing something, there is a playbook for his administration to follow.

Support Vox’s explanatory journalism

Every day at Vox, we aim to answer your most important questions and provide you, and our audience around the world, with information that empowers you through understanding. Vox’s work is reaching more people than ever, but our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources. Your financial contribution will not constitute a donation, but it will enable our staff to continue to offer free articles, videos, and podcasts to all who need them. Please consider making a contribution to Vox today, from as little as $3.

Sourse: vox.com