Back in 2016, Donald Trump got about 46 percent of the vote nationally, 2 percentage points less than Hillary Clinton. But his support was so artfully distributed that he earned the crucial electoral votes of Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, and Michigan.

Two years later, his party got creamed in elections of the US House of Representatives, losing 35 to 40 seats despite a map whose geography favors the GOP even more strongly than the Electoral College does. It looks like, though, when all the votes from California are in, Republicans will have earned just about 46 percent of the vote nationally — almost exactly the same share as two years ago.

All that diner journalism about how Trump voters still like Trump was, in other words, pretty much on the money (at least in the aggregate). It’s just that it didn’t matter.

There were never enough Trump voters to form a majority of the electorate. And that, more than suburban backlash or anything else, is what did in Republicans on Tuesday. The Trump voters stood by Trump and voted Republican, but this time around, everyone else voted for the Democrats. And the Democrats won.

Donald Trump has never been popular

Trump stands out so strongly in the political landscape that takes often emerge that neglect to mention the fact that he had an opponent.

But the central reality of the 2016 campaign is that both major parties’ nominees were unusually unpopular. The typical scenario in 21st-century presidential campaigns has been for even the losing candidate to be viewed favorably by at least a narrow majority of the population. But 2016 gave us a unique scenario in which both nominees were underwater, leaving voters who approved of neither candidate as a crucial swing constituency.

Those voters (like everyone else) overwhelmingly assumed Clinton would win the election, lots of them voted for Jill Stein or Gary Johnson, and consequently, Trump won an Electoral College victory — even while being below 50 percent not only in the three crucial Midwestern states but also Arizona, Florida, and North Carolina.

Democrats spent the two years since the election doing what parties that lose do — recruiting a different crop of candidates, opening themselves up to some new activists and internal turmoil, and changing their messaging focus (2018 ads were all about health care, none about Trump being mean).

Trump, meanwhile, spent two years acting as if winning 46 percent of the vote was the greatest achievement in the history of American politics, when in reality, Mitt Romney and John Kerry did better than that and Michael Dukakis did nearly as well. He broke his promise to divest from his business interests, broke his promise to promulgate a health care plan that would cover everybody, and went wildly over the top in breaking his promise to lay off the tweets and behave in a more presidential manner.

Through it all, the press would stop from time to time to remark on how attuned Trump was to his base, and how perfect he was at picking various fights — with the media, with the nation of Canada, with immigrants, with the FBI’s counterintelligence division — that played to his base’s sensibilities.

This was all probably true. (Though, again, wet-noodle Romney got a higher share of the vote.) But it was also somewhat bizarre. Winning the presidency while losing the popular vote 46-48 is within the rules of the game, but it left Trump with a negative margin of error. The math was plain as day that all Democrats had to do was consolidate the people who didn’t like Trump and they’d blow the Republicans out.

But the House GOP seemed confident that their gerrymanders would hold. And then when polling in September and October suggested clearly that it wouldn’t, Trump started ranting about the caravan. The political goal here, we were told, was to rally Trump’s base to come back home, which more or less happened. Except 46 percent of the population just isn’t that many people.

Achieving unity is the key challenge for Democrats

One major advantage Democrats had in achieving unity in 2018 is that in congressional elections, you’re allowed to run different candidates in different seats.

Jared Golden, a young veteran and former Susan Collins staffer from Lewiston, Maine, is a nearly perfect candidate to run in the state’s Second Congressional District. And his campaign agenda that was heavy on bread-and-butter populism and light on racial justice was a perfect match for the district.

Jacky Rosen ran a very different race in the very different state of Nevada, reassembling the coalition of Latinos and white college-educated professionals that elected Catherine Cortez-Masto two years ago and that has now put this swingy state under total Democratic control.

Lucy McBath rallied a very different coalition, likely the coalition of Democrats’ long-term future, in a diverse, largely upscale district in the favored quarter suburbs of Atlanta, while Jon Tester of Montana and Sherrod Brown of Ohio gutted out wins in red states based on old-school labor liberalism.

The challenge in a presidential race is that you only get to run one candidate in a varied country.

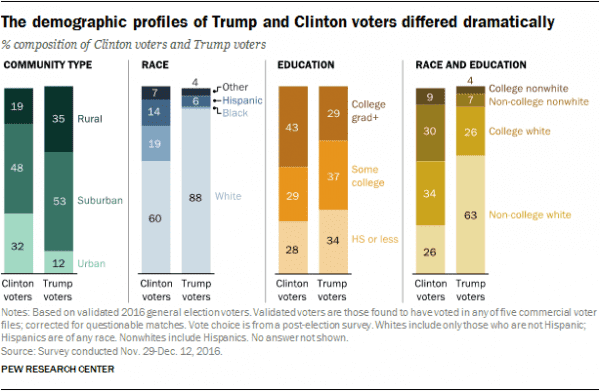

Trump has the same challenge. But his advantage is that while his base is not a majority of the country, it is very homogeneous. Almost 90 percent of Trump voters were white, and more than 70 percent had no college degree. That means some very basic appeals to white working-class identity politics plus the promise of anti-abortion judges for college-educated evangelicals hold the base together.

Clinton’s coalition, by contrast, was about one-third white professionals and about one-third working-class minorities (themselves split between black and Latino voters). About a quarter were working-class whites, joined by a smaller, but influential, group of college-educated nonwhites.

Holding this group together is objectively difficult. Golden’s biography, personality, and platform that worked in Maine probably wouldn’t appeal that strongly to McBath’s constituents in Nevada, and McBath would struggle to appeal to Golden’s constituents. The Trump voters who still like Trump aren’t a majority, but to assemble a majority, you do need to rope them all together, and that’s tough.

But tough doesn’t mean impossible.

Charisma — the X-factor that put JFK, Bill Clinton, and Barack Obama in the White House, powered Beto O’Rourke to an unprecedented performance for a Texas Democrat, and made an instant superstar of Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez this summer in New York — is a traditional part of the formula. But so is fear. Clinton was handicapped in 2016 not only by some of her own shortcomings as a candidate but by the basic reality that everyone thought she would win, so nobody felt like being a cheap date.

By 2018, everyone knew better. And if they feel the same in 2020, Trump is doomed.

Sourse: vox.com