President Trump is sharply escalating his criticisms of the Federal Reserve, saying the Central Bank has “gone crazy” in impromptu remarks in response to Wednesday’s stock market crash, and then escalating his critique during a Wednesday phone interview with Fox News.

“The problem I have is with the Fed,” he told Fox’s Shannon Bream, pushing back on allegations that trade tensions with China were roiling financial markets. “The Fed is going wild. They’re raising rates and it’s ridiculous.”

Delving further into the nuances of monetary policy, he added that “the Fed is going loco.”

The Fed is not, in fact, “going loco.” It’s continuing with a course it’s been on since at least 2016, and one that most economists and financial industry professionals think is appropriate. Just because the Fed is following the conventional wisdom among insiders doesn’t mean that it’s necessarily correct — there’s a strong case on the merits that Trump is right and more patience would be better for the country as a means of promoting further healing in the labor market.

That said, Trump is not making this case with any kind of rigor or clarity. Worse, he’s not conducting policy in the appropriate way — by appointing Federal Reserve Board of Governors members who agree with him.

On the contrary, to the extent that his pending nominees have a lean on this issue, it’s in the opposite direction of what Trump is pushing for this week. This is a reflection of his own poor grasp of policy and his inattention to detail.

In a best-case scenario, Trump is not going to accomplish anything with his public display. And in a worst-case scenario, he’s simply going to introduce extra chaos into the system and compel monetary policymakers to do the opposite of what he’s asking for so they can demonstrate their independence from an erratic and seemingly uninformed president.

The Federal Reserve is continuing to raise interest rates

The context for all of this is the challenge of what to do when the economy is doing fine. There’s a main way monetary policy works: When the economy is weak, the central bank cuts interest rates to boost growth. But when the economy is at risk of inflationary overheating, the central bank raises interest rates to restrain growth.

During the financial crisis of 2008, the Fed cut interest rates all the way to zero, and that didn’t boost the economy enough to prevent a catastrophic recession. Over the years, the Fed undertook three rounds of “unorthodox” monetary policy known as “quantitative easing” in an effort to bolster growth. For its trouble, it faced massive criticism from Republicans.

These inflationary concerns were entirely misguided, and instead we got a slow but steady recovery featuring low inflation and years of high unemployment.

Starting in the fall and winter of 2015, when the labor market finally started to look kinda sorta okay, calls came pouring in for the Fed to “normalize” and raise interest rates even though inflation was still low and the employment-population ratio was still depressed. The central bank gave in to these pressures starting in the spring of 2016 and has been slowly raising rates ever since.

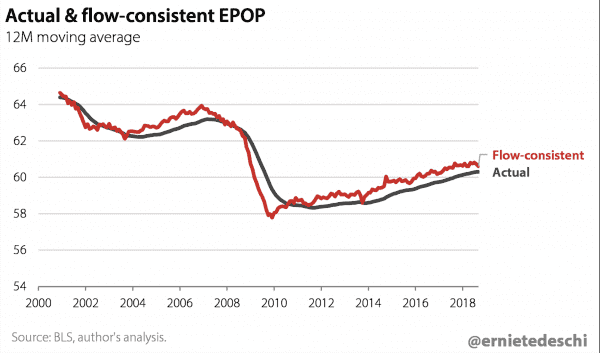

It’s clear from the past two years’ worth of job growth that the country was not, in fact, at full employment in the spring of 2016. There was no particular need to have spent 2016 and 2017 raising interest rates. The near-record lows of unemployment that we’ve achieved in 2018 could have been achieved earlier had the Fed been more patient.

That said, by today, the case for raising interest rates is stronger than it was two years ago. The unemployment rate is very low, and new data released Thursday morning indicates a 2.2 percent inflation rate, which, though by no means high, also isn’t low.

So there’s nothing particularly “wild” or “loco” about what the Fed is doing, nor is there any particular reason to believe that Fed action is responsible for Wednesday’s stock market move. What’s more, in general, you don’t see presidents engaging in public spats with the Fed.

The Fed and the White House aren’t supposed to fight

The Fed is a bit like the FBI in that, constitutionally speaking, it’s part of the executive branch of the federal government with a chief appointed by the president and who the president could theoretically fire.

In practice, though, no Fed chair has ever been fired by the president. The universal understanding in Washington, on Wall Street, and around the world is that the Fed operates independently of the White House. As we saw when Trump fired FBI Director James Comey and then took control of a background investigation into his Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh, these norms only last as long as they last.

The reason for the Fed’s operational independence is that economists are very worried about the incentive structure of monetary policy.

If you’re the president, you always benefit politically from monetary policy being a little more growth-oriented to boost your approval rating. But if policy is always shaded in the direction of being growth-oriented, then you’re going to get a spiral of inflation that ultimately undermines growth.

What you need, economists think, is an independent institution that’s insulated from politics and thus can afford to “take the punch bowl away” before the party gets out of control.

Indeed, this operational independence is considered so sacrosanct that after Ronald Reagan’s administration, presidents adopted a norm of never even commenting on monetary policy. That’s in part because of the theory that such comment is inappropriate on the merits.

But if you speak to people who worked in the Clinton, Bush, and Obama White Houses and Treasury Departments, they’ll say more bluntly that they worried commentary would backfire by essentially forcing the Fed to do the opposite of what the White House asked for to demonstrate their independence.

The empirical evidence showing that this incentive problem is really a problem is actually quite thin, but it deeply structures the conventional conduct of monetary policy and makes Trump’s criticisms big news.

Trump might be right, or he might be rambling incoherently

Back in 2016, I was absolutely convinced that the Fed skeptics were correct and that people who were backing higher rates (like Donald Trump at the time) were making a huge mistake. Subsequent events have vindicated that position, and analysis from Adam Ozimek at Moody’s that suggests premature rate-hiking cost the economy about a million jobs over two years.

The situation as of today is less clear, but there continues to be evidence that the employment rate is depressed in historical terms. And while inflation isn’t low anymore, it’s not high either.

The Fed’s view is essentially that interest rates have been very low for a long time, and now that the economy is reasonably healthy, it’s a good idea to get them back up sooner rather than later. The contrary view is that the labor market was very sick for a very long time, so it’s a good idea to err on the side of too much job creation for a little bit to help the long-term unemployed get back to work and to shock employers into acknowledging that in the future, they are going to need to offer pay raises if they want to fill vacancies.

But while I think Trump is probably correct about the Fed, his actions as president seem to call into question whether he thinks he is correct about the Fed. There are, right now, three vacancies on the Federal Reserve Board of Governors and three Trump nominees making their way through the confirmation process.

One of them, Michelle Bowman, is a Kansas bank regulator with no known views on monetary policy. The second, Nellie Liang, is a well-qualified, longtime staff economist at the Fed whose views are almost certainly in line with the existing Fed consensus. And the third, Marvin Goodfriend, is a longtime inflation hawk who thinks the Fed has been raising rates too slowly rather than too quickly.

So if Trump actually wants to see a more growth-oriented monetary policy, he should probably cool it with the name-calling, withdraw Goodfriend, and instead put forward someone who agrees with him.

The problem is that when you have a president who doesn’t really understand any area of public policy or care to take the time to learn about it, it’s difficult for him to be effective, even when his instincts make some sense.

The risk is that by publicly beefing with the Fed even while not staffing the board properly, he is going to generate a counterproductive response as the Fed feels compelled to keep raising rates just to show Trump isn’t micromanaging the process.

That would be a form of sweet schadenfreude for Trump haters, but also a tragedy for potentially hundreds of thousands of Americans who might lose out on the opportunity to get a job.

Sourse: vox.com