The resistance is now on offense. Democrats’ takeover of the House gives President Donald Trump’s opponents something they haven’t had till now: the power to force Trump to respond to them rather than being forced to respond to Trump.

But it also gives Trump something he hasn’t had since taking office: a political opposition with power, with leaders, with legislation he can attack. Trump has never liked negotiating the details of policy or overseeing the nuts and bolts of governance. Now he’s freed from the drag of signing and defending bills crafted in House Speaker Paul Ryan’s office.

This is why the president, in his post-election press conference, sounded almost happy to have lost the House.

Reflecting on the prospect of Democrats investigating him and him retaliating by investigating them, Trump was cheerful. “It will probably be very good for me politically,” he said. “I can see it being extremely good politically. I think that I am better at that game than they are, actually. But we will find out.”

A Democratic House permits Trump to engage in a politics of pure confrontation, which is the politics he prefers, and arguably the politics in which he thrives.

“During the 2016 campaign, we noticed this paradox,” says Ron Klain, who served as chief of staff to vice presidents Al Gore and Joe Biden and was a top adviser to Hillary Clinton. “If you came at Trump on the stuff where you thought he’d be most vulnerable — his shitty business practices, his use of non-American workers — he was at his best. He knows that stuff.”

Trump’s weakness, Klain continued, was policy. “When you came at him on that stuff, he was horrible.”

This proved true in 2018. As abnormal as American politics has felt in these past few years, House Democrats ran a fundamentally normal campaign, and it worked. They ran ads about protecting people with preexisting conditions and working on behalf of the middle class. They released their “Better Deal” agenda, a policy platform that ranged from raising the minimum wage to strengthening labor unions to investing in broadband to making campaign finance more transparent.

They did not, as a party, run on investigating or impeaching Trump. They did not, as a party, run on abolishing Immigration and Customs Enforcement or passing Medicare-for-all. They did not, as a party, offer an equal but opposite reaction to Trump. Their campaign seemed to exist in an alternate universe, one where Jeb Bush had been elected president and had repealed Obamacare, and where few had ever heard the words “Russia” or “Mueller.”

They won. The question is whether they have the discipline, or even the power, to hold to that strategy outside of an election.

Why Democrats ran on policy but might govern through investigation

If you want to see why Democrats ran the campaign they did in 2018, read the exit polls.

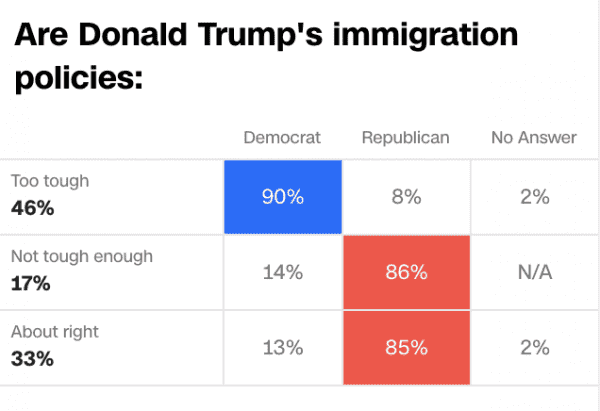

A majority of voters thought the Mueller investigation was “politically motivated” rather than “mostly justified.” A larger majority opposed impeaching Trump. Perhaps most worrying for Democrats who want to focus on Trump’s ugliest affronts, 33 percent of voters thought Trump’s immigration policies were “about right,” and another 17 percent wanted to see them toughened; only 46 percent thought Trump had gone too far.

And remember: These are exit polls from the 2018 House election. These are exit polls measuring an electorate that voted overwhelmingly for Democrats.

In a fascinating postmortem on House Democrats’ strategy, the New York Times reports that the House Majority PAC “carried out two intensive research projects, studying right-of-center suburban voters and blue-collar whites who supported Mr. Trump. It concluded that only a message about health care and jobs could win over both groups.”

So that’s the campaign House Democrats ran. Discipline was the watchword. Nancy Pelosi, when confronted with something of importance to progressives but of danger to her message, became fond of saying, “Those things are in our DNA, but they are not in our talking points.”

Rep. Ben Ray Lujan (NM), who ran the Democrats’ campaign efforts, was even more explicit. “Every time he would say something or tweet something, it would come back: ‘We need to come right back at him! Define him!’” Lujan told the Times. “We would say: Look, we don’t need to talk about him, he’s going to do it himself. We need to continue to have a conversation with the American people about kitchen-table issues.”

But message discipline is easier when you’re running paid ads than when you’re fighting to get coverage in a media environment tuned to Trump’s antics and hungry for high-stakes confrontations. House Democrats will be able to pass bills, but they won’t be able to force the Senate to take up those bills, much less demand Trump sign them. And the media rarely covers bills that can’t pass.

What House Democrats can do is investigate, and so they will. “House Democrats plan to probe every aspect of President Trump’s life and work, from family business dealings to the Space Force to his tax returns to possible ‘leverage’ by Russia,” reports Axios, quoting one senior Democrat as saying they’re preparing a “subpoena cannon.”

The incentives are clear. Investigations are what their base wants them to do, and what the media will cover them doing, and what Trump is preparing for them to do.

Among House Democrats, this is a constant topic of conversation — and of concern. Beyond the Russia investigation lies shocking levels of administrative corruption. Constitutionally, it is part of their duty to provide oversight of an executive branch in sore need of it.

But they fear unleashing confrontations they can’t control. They fear a race for coverage in which any time a Democrat utters the word “impeachment” it makes headlines but their messaging, and legislating, on the minimum wage goes unnoticed. They can see that ambitious 2020 aspirants, like billionaire Tom Steyer, are already trying to lead an impeachment charge that has no chance in the Senate and could endanger a House majority that hinges on holding at least some districts Trump won.

“I think I’m the only member of the House or Senate who was involved in both the Nixon and Clinton impeachments,” says Rep. Zoe Lofgren (D-CA), who worked as a staffer on the Judiciary Committee during Watergate and was elected to Congress in 1995. “If Mueller sends us an exploding bomb, we may have an obligation to deal with that. But absent that, I don’t think the country will be on board with impeachment, and nor should we.”

The problem, she says, is that impeachment, and the spiraling investigations that lead to it, keeps the entirety of attention on the Trump circus.

“Trump’s sideshow has an audience,” she continues. “We magnify that audience when we pay attention to that rather than what matters to people.”

Trump’s weakness is policy. Can Democrats exploit it?

Talking in terms of sideshows and audience and attention is a reminder that the question isn’t just what Democrats do — it’s what the public sees them doing. And that means it revolves around what the media focuses on. If Democrats are passing bills over here and pursuing impeachment over there, the bills will be ignored. And every single day, they will be competing for control of the media’s agenda with Trump, and Trump’s Twitter feed.

If Democrats are going to have any chance of controlling their message, it will require an almost inhuman level of discipline.

Klain, the Democratic strategist, offered an unexpected piece of counsel to his party the day after the election. “However tempting it might be for freshly empowered congressional Columbos,” Klain wrote in the Washington Post, “not a single subpoena should fly in the first 100 days.”

Instead, he wrote, House Democrats should spend their first 100 days passing big pieces of legislation that would force Trump to choose between his populist posturing and Republican orthodoxy: a $15 minimum wage, an expansion of the Affordable Care Act, a serious infrastructure bill.

When we spoke, Klain said he offered this advice for a few reasons. First, he said, “Democrats need to make it unquestionably clear to the American people that their first priority is helping the country, not damaging Trump.”

Klain served in both the Clinton and Obama administrations, and both offer a cautionary tale to House Democrats who believe a strategy of maximum confrontation will rid them of Trump in 2020. Both Clinton and Obama lost the House in their first midterm election, with approval ratings very much like Trump’s now. Both then faced a House Republican majority with no agenda other than their destruction. And both were able to pivot off that opposition to reelection, as voters grew exhausted and disillusioned with a Republican Party that seemed interested in nothing but the next campaign.

Second, Trump is at his weakest on policy, in part because he understands it so poorly, and in part because it puts him crosswise with his own party.

“Trump’s problem has always been that he’d be happy to cut a deal, but every time he tries to do it, his own party holds him back,” Klain said. “He doesn’t understand the policy issues, and he’s intimidated by his party. He doesn’t want to cross them. And do you think Mitch McConnell will slam a $15 minimum wage bill through the Senate?”

Political confrontations often leave Trump polarizing but clearly in control. Policy confrontations, on the other hand, tend to leave him looking overmatched. He seems less like a tough-talking populist than an in-over-his-head plutocrat (“nobody knew that health care could be so complicated”).

That isn’t to say Democrats shouldn’t investigate Trump, says Klain. They should. They just need to take the time to get it right. “Having worked on the Hill, it takes time to do oversight well. Who are the right witnesses? What are the right facts? What are the right documents? They need to hire staff. They need to get prepared.”

“Look at the Republicans,” continues Klain. “They’d do a hearing that they weren’t ready for. Then they’d need to do a second hearing to make up the first one. Trump is at his most dangerous is when you shoot at him and miss. You need to have it nailed.”

Investigations, if done right and chosen well, can also support a broader policy argument. “There’s a lot of revelations about ways the Trump administration has enriched itself at the expense of people,” says Ben Wikler, the Washington director of MoveOn.org. “Those are bread-and-butter politics in any era, but there’s a lot more bread and a lot more butter under Trump. The point of oversight is to show whose side Trump is on.”

To Wikler, the investigations strategy and the policy strategy are more unified than people give them credit for. There’s already a Mueller investigation, he told me. Democrats don’t need to replicate it. What they need to do is use investigations to break Trump’s claims to populism and his control over the news cycle.

“Think about Scott Pruitt,” says Wikler. “Every time a new soundproof booth or insanely expensive tactical pants became known, people were talking about the corruption of Trump’s EPA chief rather than whatever Trump tweeted that morning.”

Will any Democratic plan survive first contact with Trump?

In the final weeks before the election, the Washington Post and the New York Times ran more than 115 stories about a slow-moving caravan of Honduran asylum seekers that was more than 1,000 miles from the US border.

“Many of these articles are, on their own merits, laudable,” wrote Media Matters’ Matt Gertz in a thoughtful analysis. “They provide the compelling stories of the migrants themselves, debunk the president’s lies and conspiracy theories, and point to the facts that undermine his demagoguery. But the sheer volume of the coverage can’t help but fuel Trump’s claims that the caravan’s approach represents a crisis and suck oxygen away from other stories in the lead-up to the midterm elections.”

Why did the media converge on caravan coverage? Because Trump began tweeting about it in outrageous, offensive, bizarre ways. Much of the media’s coverage focused on debunking or complicating Trump’s narrative, but in letting that coverage reach saturation levels, the media let Trump control the narrative and push dozens of worthier stories out of the headlines.

Most politicians try to distract from controversial stories by turning the media’s attention to positive stories. Trump distracts the media’s attention from controversial stories by turning its attention to other controversial stories — the ones that he thinks serve his purposes.

Consider what he’s done in just the few days since the election. He’s fired Attorney General Jeff Sessions and replaced him, perhaps unconstitutionally, with an unqualified loyalist. He signed a proclamation overhauling asylum rules. He took away a CNN reporter’s White House press pass and tweeted a misleading video of the confrontation.

Trump doesn’t want to talk about infrastructure or raising the minimum wage. He wants politics consumed by the confrontations he prefers, the ones that mobilize his supporters. He doesn’t know how to govern the country. But he does know how to govern our attention. He does know how to manipulate the media.

The question for any strategy House Democrats might pursue is whether they can hold the media and the public’s focus amid Trump shouting and tweeting and waving his arms for everyone to look over there!

Democrats’ best shot is to go big on policy

In an interview the day after the election with Rolling Stone, Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) pointed out how easily Trump was retaking control of the agenda:

Sanders’s answer to this? “I believe it’s terribly important that the Democrats come out of the gate full-steam ahead and start passing really good legislation that puts Trump and the Republicans on the defensive,” he said.

Sanders is one of the few politicians in Washington who can match Trump’s talent for driving media attention to the topics he cares about, and he does it, again and again, by going big, by crafting massive proposals that may not be able to pass but can inspire.

It was telling, two weeks before the election, that the White House’s Council of Economic Advisers brought out a bizarre and widely panned report attacking socialism in general, and Medicare-for-all in particular. It was a rare instance of the White House responding to Democrats — particularly Sanders — rather than the other way around.

What Sanders understands, and what Trump understands, is that you don’t shape attention by crafting compromise policies; you shape attention by creating controversy. Trump does it, well, the way Trump does it. Sanders does it by using big, controversial policies to draw contrasts and start fights.

Now Sanders is urging House Democrats to orient their health care push around an expansion of Medicare that there’s no way Senate Republicans would touch, but that would be a big enough fight for the media to cover, and that would either force Trump to break with McConnell and the Senate Republicans or to show himself up as a phony populist. That’s a very different strategy than where House Democrats seem to be going, which is a package of technocratic, and negotiable, proposals to lower drug prices.

“The challenge Democrats have is that Trump does not negotiate in good faith or follow through on commitments in good faith,” says Wikler. “As much as Democrats like to pass laws that make people’s lives better, to do so involves making devil’s bargains with a devil who lives up to his reputation.”

Wikler worries that Democrats will get caught in negotiations with Trump where they make painful compromises for deals that Trump abandons as soon as he sees them panned on Fox & Friends — and so they’ll end up discouraging their base and helping no one.

“Democrats absolutely should pass a $15 minimum wage bill through the House,” he says. “What they shouldn’t do is negotiate significant compromises with Trump on issues that matter to them in order to get a minimum wage bill through.”

To fight and win against Trump, Democrats are going to have to force Trump to engage on the policy issues where he’s weak, and that means forcing the media and the public’s focus to issues he doesn’t understand and doesn’t want to talk about, and being disciplined about which of his provocations to respond to. This will be an era of conflict, not compromise. It will be a war for something Trump understands and Democrats typically don’t: attention. They’re going to have to figure it out fast.

Sourse: vox.com