There are plenty of evidence-based ideas that could help end the opioid epidemic, from more access to addiction treatment to harm reduction efforts. But the policy proposals to enact such ideas often have trouble getting off the ground — largely thanks to resistance from the general public and politicians, even in the midst of what amounts to the deadliest drug overdose crisis in US history.

A new survey of more than 5,500 Americans by Civis Analytics provides some hints for advocates looking to build public support for policy responses to the opioid crisis. The survey gauged public support for medications used to treat opioid addiction and needle exchanges, both of which have decades of evidence to support them. The analysis then compared how different messages affect levels of support among the general public.

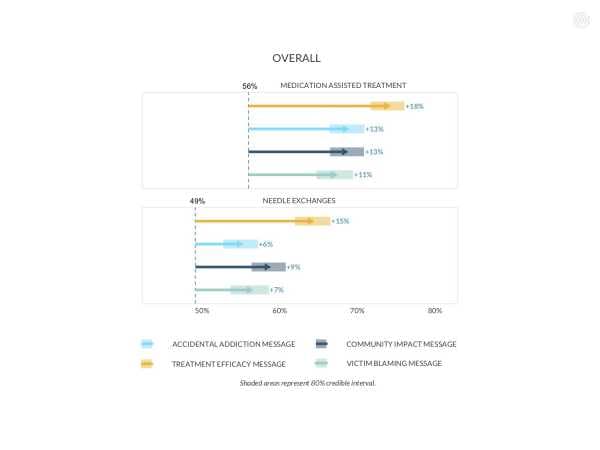

The survey established that, at a baseline, 56 percent of Americans support medications for opioid addiction and 49 percent backed needle exchanges. Afterward, it put four messages to the test, Civis explained:

- An “accidental addiction” message that framed addiction as an unintentional outcome — the result of, say, someone getting addicted to opioids while taking them after a surgery.

- A “community impact” message that emphasized the damage addiction can have on families and communities.

- A “treatment efficacy” message that pointed to the evidence behind opioid addiction medications and needle exchanges, and noted that they have been used successfully to combat addiction and overdose crises in other countries.

- A “victim blaming” message that framed people addicted to opioids as weak-minded. As a message that plays to the stigma surrounding addiction, this was included to see if it could lead to backlash.

Surprisingly, all four messages — even the “victim blaming” one — appeared to increase support for opioid addiction medications and needle exchanges. Here are the full results:

The “victim blaming” message’s success “was counterintuitive to us,” Crystal Son, one of the Civis researchers, told me. “This is just my hypothesis about it, but I think that even when you’re blaming it on the victim, there’s still a recognition that there’s a societal impact and that this is a problem, and so there needs to be something done about it.”

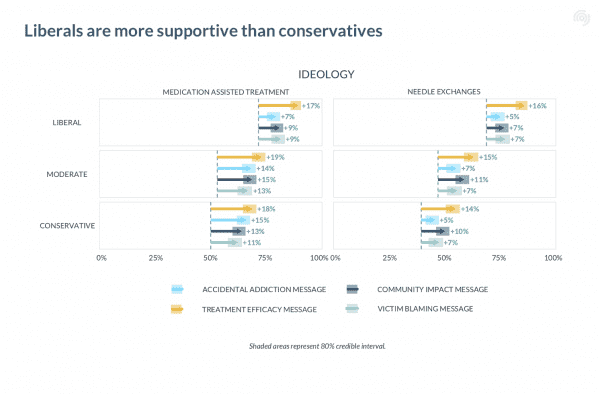

This applied across the political spectrum, although different subgroups were affected in various ways by the messages.

Here’s the breakdown by political ideology:

I found the results particularly notable for needle exchanges, since they show that you can get a majority of conservatives to back needle exchanges with a message that emphasizes their effectiveness.

Needle exchanges, where users can pick up sterile syringes and trade in used needles, have a lot of evidence behind them. The decades of research show needle exchanges combat the spread of bloodborne diseases like hepatitis C and HIV, cut down on the number of needles thrown out in public spaces, and link more people to treatment — all without enabling more drug use.

But needle exchanges remain fairly scarce in the US. Consider this fact, reported by Josh Katz at the New York Times: “According to the North American Syringe Exchange Network, 333 such programs operate across the country, up from 204 in 2013. In Australia, a country with less than a tenth as many people, there are more than 3,000.”

Much of that scarcity is driven by public opposition, particularly local resistance that takes form in a not-in-my-backyard (NIMBY) sentiment that, in short, argues that allowing needle exchanges will attract more drug users to an area and lead to more drug-related problems. That’s contrary to much of the evidence noted above, but it’s a real concern — one that is particularly prevalent in conservative parts of the country, where needle exchanges are much less common.

The survey appeared to dispel or at least mitigate some of these concerns by telling people of successes with needle exchanges in other countries — like France, which successfully combated its own opioid crisis in the 1990s in part with needle exchanges and more access to medication-based addiction treatment.

This is just one survey. It’s not the final word on what messages work best, especially the messages that weren’t included. It’s also possible that different wording than was used in the survey could change the results. And it’s unclear how long the higher levels of support remain; it’s possible, for example, that the higher levels of support for, say, needle exchanges would fade over time, particularly if people are exposed to messages from the opposition.

It’s also uncertain why some messages work well and others don’t work as well. The researchers have some hypotheses — maybe the “accidental addiction” message was less effective than others because it’s been widespread in the current opioid crisis, so there “might be a kind of exhaustion of hearing that message,” Son said. But the study didn’t dig into that, so the researchers don’t know for sure yet.

Still, Civis’s analysis suggests that there really are messages that can meaningfully increase support for some strategies in combating the opioid crisis, and therefore actually get such policies implemented in the real world. With the opioid crisis now killing tens of thousands of Americans each year, that means these messages could save lives.

For more on solutions to the opioid epidemic, read Vox’s explainer.

Sourse: vox.com