President Donald Trump’s Department of Justice seems to have a new enemy: progressive prosecutors.

The latest volley from the Justice Department came after a shooting in Philadelphia injured six police officers. William McSwain, the federal prosecutor who heads the US Attorney’s Office for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, released an unusual statement on Thursday in which he blamed the shooting on Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner, a progressive prosecutor who has made it his mission to end mass incarceration and the war on drugs.

“We’ve now endured over a year and a half of the worst kinds of slander against law enforcement — the DA routinely calls police and prosecutors corrupt and racist, even ‘war criminals’ that he compares to Nazis,” McSwain claimed in the statement. “This vile rhetoric puts our police in danger. It disgraces the Office of the District Attorney. And it harms the good people in the City of Philadelphia and rewards the wicked.”

The day before, McSwain went on Tucker Carlson’s Fox News show to blast Krasner in light of the shooting of six police officers.

The shooting suspect, Maurice Hill, had a long criminal record and was able to get a gun and shoot police officers, so this might seem like an attempt to cast blame — although Hill also has a federal criminal history and was known to the feds, so it’s not clear why Krasner’s office would be any more to blame than McSwain’s.

But this goes beyond one shooting. McSwain’s and Krasner’s offices have actually been clashing since last year, usually with McSwain criticizing Krasner for an individual case, leading Krasner to fire back.

McSwain’s concern appears to be a philosophical disagreement with Krasner’s approach and criminal justice reform in general. On Fox News, McSwain claimed that due to Krasner’s progressive policies, “homicides and shootings have skyrocketed” since Krasner took office in 2018. (In fact, the number of homicides so far this year is roughly in line with the previous two years, and is down roughly 25 percent since 2007.)

These criticisms of progressive prosecutors go all the way to the top of Trump’s Justice Department — to Attorney General William Barr. Earlier this week, Barr criticized progressive prosecutors in a speech to police. He didn’t name Krasner or any other prosecutor, but he argued that “the emergence in some of our large cities of district attorneys that style themselves as ‘social justice’ reformers, who spend their time undercutting the police, letting criminals off the hook, and refusing to enforce the law,” is “demoralizing to law enforcement and dangerous to public safety.”

The goal of the Justice Department here is, it seems, to undermine criminal justice reform. Barr, who helped write a report titled “The Case for More Incarceration” when he was attorney general under President George H.W. Bush, has long been critical of efforts to pull back punitive criminal justice policies, from aggressive policing to longer prison sentences. McSwain, as a US attorney, is helping his boss get the word out by targeting Krasner, who’s widely known in criminal justice circles as a reformer.

One of the problems for Barr is his office actually doesn’t have much power in the overall criminal justice system, because most of the system’s work happens at the local and state levels. That makes local district attorneys like Krasner, who effectively decide who goes to prison and what they’re charged for in local and state systems, uniquely powerful. But since Barr has limited influence on what local prosecutors do, he’s trying to use his bully pulpit — and seemingly that of his underlings — to fight against a rise in prosecutors using their unique powers for reform.

Krasner, for his part, doesn’t seem fazed, dismissing McSwain’s criticisms in a statement to Vox.

“The US attorney is not a political elected office,” he said. “I’m surprised that William McSwain would seek to detract from the great collaborative work of law enforcement last night — for which bipartisan leaders in City Hall just minutes ago had nothing but praise, and rightly so — for his own political agenda and personal gain.”

He added, “Thank you for your question, but I will not be part of a distraction from the serious work before law enforcement in Philadelphia, which is to fully investigate this assault on our police officers and neighbors, and to bring the perpetrator — and any co-perpetrators — to justice.”

Progressive prosecutors are key to criminal justice reform — and the Trump administration knows it

Typically, discussions of the criminal justice system focus on lawmakers, prisons, the police, and maybe judges. Rarely, however, is the most powerful actor in this system mentioned: the prosecutor.

Prosecutors are enormously powerful in the US criminal justice system, in large part because they are given so much discretion to prosecute cases however they see fit. For example, after Krasner was elected and took office in 2018, he sent out a memo ordering his office to, among other policy changes, not charge people for the possession of marijuana, offenses related to drug paraphernalia if the case is about marijuana, and prostitution if the sex worker has two or fewer convictions.

So marijuana and prostitution remain illegal in Philadelphia and Pennsylvania, but the city’s district attorney said that he would ignore those aspects of the law — and it was completely within his discretion to do so.

Prosecutors make these types of decisions all the time: Should they bring the type of charge that will trigger a lengthy mandatory minimum sentence? Should they bring a charge that’s only a misdemeanor? Should they strike a deal for a lower sentence, but one that can be imposed without a costly trial?

Courts and juries do, in theory, act as checks on prosecutors. But in practice, they don’t: More than 90 percent of criminal convictions are resolved through a plea agreement, so by and large, prosecutors and defendants — not judges and juries — have almost all the say in the great majority of cases that result in incarceration or some other punishment.

In this sense, the Justice Department is right: Local prosecutors are very powerful, and some of them, including Krasner, really are using their power to undermine existing laws that they see as far too punitive.

But there’s nothing illegal or scandalous about this. Prosecutors have always had this type of discretion. It’s just that before, the discretion was used to try to obtain the most punitive prison sentences possible — sometimes contrary to what even the judges overseeing such cases would have preferred — during an era when “tough on crime” politics and incredibly harsh sentences for even low-level violations, from drugs to theft, were popular.

In fact, John Pfaff, a criminal justice expert at Fordham University, has found evidence that prosecutors have been the key drivers of mass incarceration in the past couple of decades. Analyzing data from state judiciaries, he compared the number of crimes, arrests, and prosecutions from 1994 to 2008. He found that reported violent and property crime fell, and arrests for almost all crimes also fell. But one thing went up: the number of felony cases filed in court.

Prosecutors were filing more charges even as crime and arrests dropped, throwing more people into the prison system. Prosecutors were driving mass incarceration.

In recent years, though, voters have increasingly come around to a vision that the criminal justice system has become too punitive. America incarcerates more people than any other country in the world — even more than totalitarian countries like Russia and China — and there are big racial disparities throughout the system.

That’s led to calls for reform. Notably, polls show both liberals and conservatives support at least some reforms. Even Trump, who ran on a “tough on crime” platform, signed criminal justice reform into law with the First Step Act.

But Barr has long been critical of these efforts. He was an architect of mass incarceration, helping promote more punitive criminal justice policies at the federal and state level in the 1990s. He also criticized President Barack Obama’s Justice Department for its investigations of abusive police departments and efforts to discourage aggressive policing practices that disproportionately hurt minority communities, while praising Trump’s first attorney general, Jeff Sessions, for pursuing harsher prison sentences against drug offenders. He’s critical of legalizing marijuana, and has argued that the criminal justice system does not treat people differently based on race.

McSwain echoed the sentiment. “Criminals are the winners in this story,” he said on Fox. “Mr. Krasner makes no bones about this. He’s not even pretending to be a prosecutor. He calls himself a public defender with power. It’s almost like letting the fox into the henhouse.”

The Trump administration says crime will skyrocket under progressive policies. That’s not backed by the evidence.

In his speech earlier this week, Barr warned that the results of less punitive criminal justice policies “will be predictable: more crime; more victims.” This seems to be the core basis for his support of “tougher” criminal justice policies.

The evidence, however, suggests that harsher criminal justice policies do not actually keep people safer.

A 2015 review of the research by the Brennan Center for Justice estimated that more incarceration — and its abilities to incapacitate or deter criminals — explained about 0 to 7 percent of the crime drop since the 1990s, though other researchers estimate it drove 10 to 25 percent of the crime drop since the ’90s.

Another huge review of the research, released in 2017 by David Roodman of the Open Philanthropy Project, found that releasing people from prison earlier doesn’t lead to more crime, and that holding people in prison longer may actually increase crime.

That conclusion matches what other researchers have found in this area. As the National Institute of Justice concluded in 2016, “Research has found evidence that prison can exacerbate, not reduce, recidivism. Prisons themselves may be schools for learning to commit crimes.”

Similarly, other research suggests that more aggressive policing strategies, such as stop-and-frisk, don’t significantly reduce crime (although by disproportionately hassling black and brown communities, they do reduce faith in police among minority neighborhoods). In fact, recent studies indicate that more targeted policing approaches, when coupled with social service programs and public health interventions in a way that fixates on the very few individuals at risk of violence, are much more effective for combating crime and murders.

To this end, a recent report by the Brennan Center for Justice concluded, “Between 2007 and 2017, 34 states reduced both imprisonment and crime rates simultaneously, showing clearly that reducing mass incarceration does not come at the cost of public safety.” Other places that have pulled back aggressive policing and criminal justice policies, such as New York City after it halted stop-and-frisk, have seen crime continue to drop.

And since Krasner took office, the number of homicides (which is often used as a proxy for violent crime) has remained relatively flat. According to Philadelphia Police, there were 205 homicides from January 1, 2019, to August 15, 2019 — up slightly from 200 during the same period in 2017, before Krasner became district attorney, and down sharply from 257 during the same period in 2007.

The Justice Department and US Attorney’s Office for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania did not return requests for comment and requests for evidence that criminal justice reform will lead or is leading to more crime.

The federal government plays a small role in criminal justice. The Justice Department may be trying to change that.

For Barr, the key concern may be that he’s seeing the system he helped build over the years start to change in a way he doesn’t like — and there’s not much, as attorney general, that he can do about it.

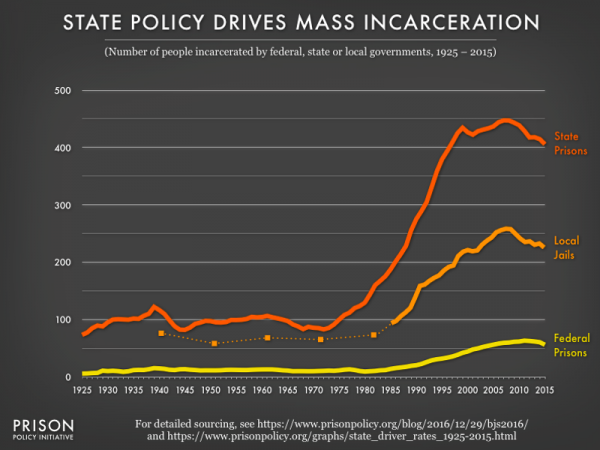

That’s because the federal government actually has a relatively small role in the US criminal justice system. Consider the statistics: In the US, federal prisons house about 12 percent of the overall prison population. That is, to be sure, a significant number in such a big system. But it’s relatively small in the grand scheme of things, as this chart from the Prison Policy Initiative shows:

One way to think about this is what would happen if Trump used his pardon powers to their maximum potential — meaning he pardoned every single person in federal prison right now. That would push down America’s overall incarcerated population from about 2.1 million to about 1.9 million.

That would be a hefty reduction. But it also wouldn’t undo mass incarceration, as the US would still lead all but one country in incarceration: With an incarceration rate of around 600 per 100,000 people, only the small country of El Salvador would come out ahead.

Similarly, almost all police work is done at the local and state level. There are about 18,000 law enforcement agencies in America — only a dozen or so of which are federal agencies.

It’s this dynamic that has led criminal justice reformers, such as liberal billionaire George Soros and the American Civil Liberties Union, to funnel resources into local and state policy changes, including by electing progressive prosecutors like Krasner and other district attorneys across the US.

But now those opposed to criminal justice reform, like Barr and McSwain, are fighting back. As McSwain put it to Carlson on Fox, “[Soros] realizes that he can’t do that through the normal democratic process. Normally, if you’re going to try to get criminal justice reform, you have to do it through the legislature, you have to get broad public support for the kind of changes that you want to institute. He’s taking what I would describe as an illegitimate, anti-democratic shortcut by trying to purchase DA elections, and then once the DA is in place, he or she doesn’t enforce the law — and, presto, you have criminal justice reform.”

The reality is that most voters, Democrats and Republicans alike, support at least some level of criminal justice reform, based on public surveys. And Krasner was democratically elected — on an explicit platform to reform the criminal justice system. That’s democracy at work.

For Barr and McSwain, though, the idea that the public might be turning against their views on these issues is apparently not something they’re willing to admit, and they’re now trying to rally the public to their side.

Sourse: vox.com