President Donald Trump’s administration has banned bump stocks, which effectively let semiautomatic weapons mimic machine guns.

The administration’s final regulation, likely to officially publish on Friday, will bring bump stocks into the broader federal ban on machine guns starting in late March 2019, forcing people who own bump stocks today to turn in or destroy the devices within 90 days. The administration originally introduced the rule in March 2018, but it needed to go through a formal regulatory approval process to take effect.

The bump stock ban originally came up in response to the Las Vegas shooting last year, in which a shooter used the devices to kill 58 people and injure hundreds more. The gunman still may have carried out the shooting without bump stocks, but the devices made the shooting much deadlier by turning his semiautomatic weapons into guns that closely simulated automatics.

Automatic weapons are what many Americans think of as machine guns. They can continuously fire off a stream of bullets if the user simply holds down the trigger, making them very deadly. Semiautomatic weapons, by contrast, fire a single bullet per trigger pull. The difference between an automatic and a semiautomatic effectively translates to firing hundreds of rounds a minute versus dozens or so in the same time frame.

Under federal law, fully automatic weapons are technically legal only if made before 1986, when Congress passed the Firearm Owners’ Protection Act. So it’s illegal to manufacture new automatic weapons for civilian use.

Bump stocks offer a way around the law, as the Associated Press explained shortly after the Las Vegas shooting:

There are other modifications that achieve a similar effect, including a crank that replaces the trigger and turns a gun into what a gun aficionado channel on YouTube called “a mini Gatling Gun.”

Shortly after the Parkland, Florida, high school shooting in February, Trump called on the Justice Department to ban bump stocks and similar devices (although the Parkland shooting did not involve a bump stock). The Justice Department’s decision to do so came despite a reluctance that the Justice Department or Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (ATF) have the legal authority ban bump stocks and similar devices.

The new regulation will likely face challenges in court.

But even if it survives, there’s a big question of just how effective the ban will be.

America needs to go much further than a bump stock ban

The bump stock ban is among several proposals Trump has made to tighten gun control after the Florida shooting, such as improving reporting to the background check system and raising the legal age for purchasing assault-style weapons from 18 to 21. Even if all these efforts were successful, it’s unclear just how much of an effect they would have — because they do little to quickly address the core problem behind US gun violence.

The US is unique in two key, and related, ways when it comes to guns: It has way more gun deaths than other developed nations, and it has far more guns than any other country in the world.

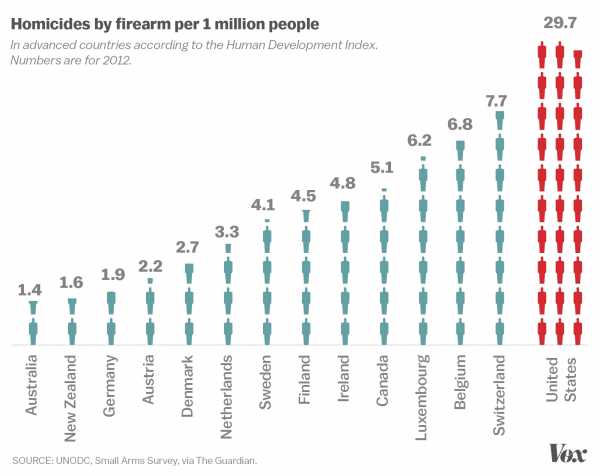

The US has nearly six times the gun homicide rate of Canada, more than seven times that of Sweden, and nearly 16 times that of Germany, according to United Nations data compiled by the Guardian. (These gun deaths are a big reason America has a much higher overall homicide rate, which includes non-gun deaths, than other developed nations.)

Mass shootings actually make up a small fraction of America’s gun deaths, constituting less than 2 percent of such deaths in 2016. But America does see a lot of these horrific events: According to CNN, “The US makes up less than 5% of the world’s population, but holds 31% of global mass shooters.”

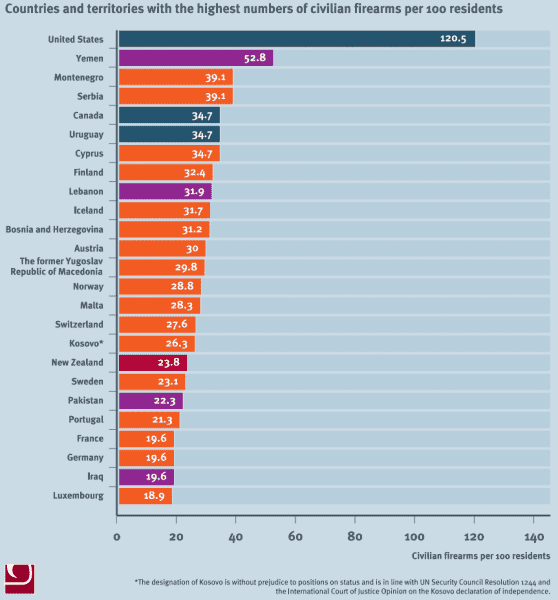

The US also has by far the highest number of privately owned guns in the world. Estimated for 2017, the number of civilian-owned firearms in the US was 120.5 guns per 100 residents, meaning there were more firearms than people. The world’s second-ranked country was Yemen, a quasi-failed state torn by civil war, where there were 52.8 guns per 100 residents, according to an analysis from the Small Arms Survey.

Another way of looking at that: Americans make up less than 5 percent of the world’s population, yet they own roughly 45 percent of all the world’s privately held firearms.

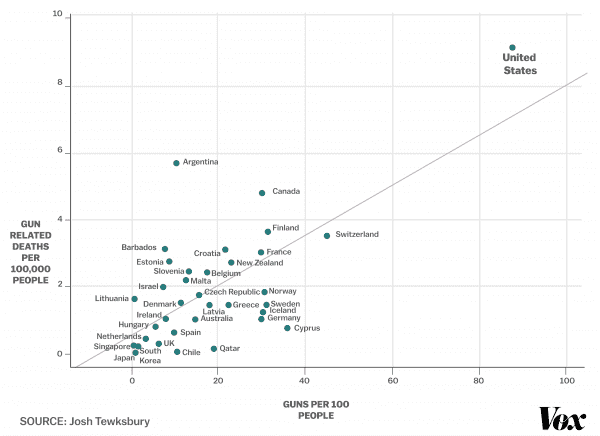

These two facts — on gun deaths and firearm ownership — are related. The research, compiled by the Harvard School of Public Health’s Injury Control Research Center, is pretty clear: After controlling for variables such as socioeconomic factors and other crime, places with more guns have more gun deaths.

“Within the United States, a wide array of empirical evidence indicates that more guns in a community leads to more homicide,” David Hemenway, the Injury Control Research Center’s director, wrote in Private Guns, Public Health.

For example, a 2013 study, led by a Boston University School of Public Health researcher, found that, after controlling for multiple variables, a 1 percent increase in gun ownership correlated with a roughly 0.9 percent rise in the firearm homicide rate at the state level.

This chart, based on data from researcher Josh Tewksbury, shows the correlation between the number of guns and gun deaths among wealthier nations:

Guns are not the only contributor to violence. (Other factors include, for example, poverty, urbanization, and alcohol consumption.) But when researchers control for other confounding variables, they have found time and time again that America’s high levels of gun ownership are a major reason the US is so much worse in terms of gun violence than its developed peers.

This is in many ways intuitive: People of every country get into arguments and fights with friends, family, and peers. But in the US, it’s much more likely that someone will get angry during an argument and be able to pull out a gun and kill someone.

Gun control measures can help address this by reducing the number of people who own guns, whether over time or immediately.

The research supports gun control: A 2016 review of 130 studies in 10 countries, published in Epidemiologic Reviews, found that new legal restrictions on owning and purchasing guns tended to be followed by a drop in gun violence — a strong indicator that restricting access to guns can save lives.

But not all gun control is made equal. Consider the specifics of the US: If the key problem is that America has too many guns, then it needs to do something to reduce the number of guns in circulation quickly — something akin to Australia’s response to a mass shooting in the late 1990s, when the country passed sweeping restrictions on firearms and enacted what was effectively a gun confiscation program for certain types of weapons. That policy not only cut the number of guns in circulation but, based on the research, may have cut the firearm homicide and suicide rates too.

The policies Trump has backed wouldn’t achieve that. They could over time reduce the number of guns in circulation — by imposing barriers that future would-be buyers won’t be able to overcome — but they don’t do anything to immediately take guns out of circulation.

In fact, this is typical in US policy responses to guns: After the 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting that killed 26, the bill Congress considered (but didn’t pass) would not have implemented even universal background checks, and it certainly wouldn’t have created a mandatory buyback program like Australia’s.

None of that is to say that milder measures aren’t effective. Connecticut’s law requiring handgun purchasers to first pass a background check and obtain a license, for example, was followed by a 40 percent drop in gun homicides and a 15 percent reduction in gun suicides. Similar results, in the reverse, were reported in Missouri when it repealed its own permit-to-purchase law. There’s similar evidence for Massachusetts’s gun license system.

And a review of the evidence by RAND also linked milder gun control measures, including background checks, to reduced injuries and deaths — and that means these measures likely saved lives.

But if America wants to get to the levels of gun deaths that its European peers report, it will likely need to go much further.

Sourse: vox.com