The most exciting business news story of 2018 ended with a whimper this week as reports surfaced that Amazon’s HQ2 project would in fact be two smaller projects, one on Long Island City in Queens and the other in Crystal City across the Potomac from Washington, DC.

Opening two regional branch offices rather than opening a gigantic “second headquarters” makes pragmatic sense. So much sense, in fact, that it’s pretty much what every other large company on the planet does when it decides its home base can’t fully accommodate its needs.

Indeed, it makes so much sense that one can’t help but believe that this was the obvious solution all along (it is, after all, exactly what other companies do) and the entire concept of a unitary second headquarters was not much more than a publicity stunt designed to entice cities and states to put forward ultra-generous benefits packages only for Amazon to later underdeliver on jobs and investment.

The question of local government subsidies to entice businesses remains an urgent one (see, for example, The Verge’s exposé of Scott Walker’s disastrous $4.1 billion Foxconn boondoggle), but the HQ2 drama in many ways reveals an even bigger policy failure than that.

Related

Amazon HQ2: the many layers of backlash against the company’s expansion, explained

Simply put, while locating large pools of high-salary white collar positions in the New York and DC metro areas makes a ton of sense for Amazon, it doesn’t actually make that much sense for either greater New York City or greater Washington. Amazon’s presence will tend to exacerbate those cities’ crises of housing affordability and overburdened transportation infrastructure.

And it makes no sense at all for the United States of America, which urgently needs more economic opportunity in dozens of other metro areas that have a different set of problems.

America needs to find a way to do better than this. Being the home to a very large share of the world’s most dynamic high tech companies is an incredible source of national strength, but in practical terms it does not benefit most Americans. With better policy it could.

What is (or was) HQ 2?

The original pitch for HQ2 was tantalizing to mayors, governors, and real estate developers all across the land when it was released in September 2017. Amazon issued a request for proposals to become the home to a vast new corporate campus that promised 50,000 jobs spread across 8 million square feet of office space at an average salary of $100,000 a piece.

This was both a huge economic development prize and a potential logistical nightmare.

Amazon wanted a new base of operations, after all, primarily because the company’s explosive growth was putting enormous strain on the city of Seattle. Despite a construction boom in the city’s relatively small downtown, most of Seattle’s land area is zoned for single-family detached houses and it is ringed by suburbs that enact even more exclusionary zoning practices. Consequently, economic growth in Seattle has proven to be a double-edged sword, with rents soaring and many working-class residents not eligible for high-paid tech jobs left behind.

The city began to address this with a dramatic minimum wage hike, but also started moving to tax Amazon and other large employers to fund homelessness services. Amazon successfully spooked the City Council out of enacting that tax earlier this year. (The tax was not very well designed, but some experts argue it was about the best the city could do given the constraints of state law in Washington.) The fight confirms Amazon executives’ judgment that piling more and more eggs into the Seattle basket is fundamentally unworkable.

Hence the HQ2 sweepstakes naturally began to immediately fuel speculation about an Amazon-driven renaissance of a city like St. Louis or Baltimore that’s fallen on difficult times.

Speculation, however, began to focus very quickly on the Washington, DC, area since Amazon founder Jeff Bezos own the Washington Post and the largest mansion in the city. What’s more, Amazon already has a major data center in Northern Virginia. (Due to the internet’s origin as a Department of Defense project and the fact that AOL was originally based there, the area holds the physical location of much of the backbone of the internet.) The DC metro area does not, however, have a particularly reasonable location for a brand new office park of HQ2-type scale. The best place for it would probably be some largely vacant land out near Dulles Airport that wouldn’t be particularly convenient to any urban lifestyle amenities.

So the plan, instead, is apparently to scale down the DC office to a size that would fit in the more conveniently located Crystal City neighborhood and supplement it with a similarly sized office in Queens. And the two locations have a bunch in common:

- Both are close to an airport (La Guardia for Long Island City, Reagan National for Crystal City).

- Both are away from the central business district, but still proximate to mass transit and right across a river from the main part of their respective cities.

- Both are full of buildings that are generally considered tacky, in neighborhoods that aren’t subject to historic preservation rules.

- Both are in metropolitan areas that are already far above the national median income and that are already suffering from some acute crises of housing supply.

Those common elements make them logical places for Amazon to establish big new offices, but also raise importation questions about whether the big new Amazon offices will actually be beneficial to anyone besides Amazon.

Adding new high-paid jobs to already expensive cities is a mixed bag

Every jurisdiction in the running for HQ2 was offering Amazon various kinds of inducements, often secretly. With the HQ2 plan apparently scrapped in favor of the splitting plan, it’s not clear exactly what Amazon will be getting in exchange.

These benefits packages are always controversial and will naturally raise the question of whether whatever the public sector will be kicking in is worth the price. But the scarier news for places like New York and DC is the evidence that an Amazon-type influx might not be beneficial at all.

Over a decade ago, housing economists Janna Matlack and Jacob Vigdor investigated the economic impact of unequal economic development and found that “in tight housing markets, the poor do worse when the rich get richer.”

A “tight” housing market, in this case, is a market like greater New York or greater Washington, where the cost of buying a house greatly exceeds the actual construction costs of new buildings. The problem in markets like this is that when the rich get richer — say because a new office complex opens and hires 20,000 to 30,000 people for six-figure salaries — the price of scarce housing rises.

If you actually get a job at Amazon or have the kind of job skills that you plausibly could get a job at Amazon, this will pay off for you because you’ll end up with higher wages that more than equal the higher rent. But if you work in a restaurant or cut hair or clean houses or a drive cab, you’ll probably end up worse off.

This is, however, not an inevitable consequence of the rich getting richer. Matlack and Vigdor find that in housing markets that are “slack” — where there is either plenty of existing housing or it is easy to build new homes so that sale prices approximately equal construction costs — there are spillover benefits. In a slack market, the new rich people don’t impact rents very much but their presence creates new working-class job opportunities. In the right location, in other words, a big new Amazon office park could have been a boon. But America didn’t get the right location.

Tight markets could be less tight

Of course, the fact that the housing markets in the DC and New York areas are “tight” is not a fact of nature.

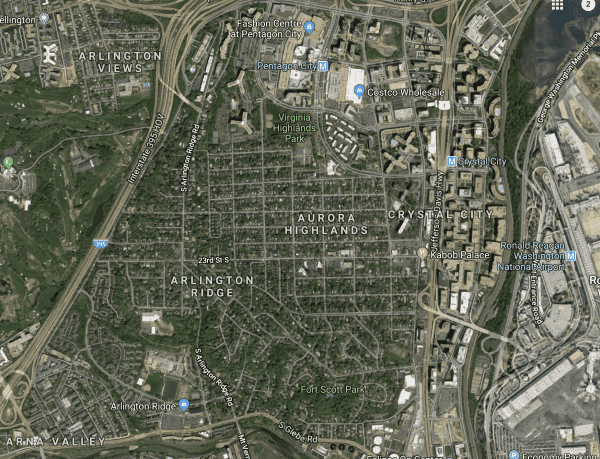

This is especially clear in the case of Crystal City, which is part of a small dense corridor of development east of the highway US 1 that is immediately adjacent to the low-density single family home neighborhoods of Aurora Highlands and Arlington Ridge.

There’s nothing wrong with detached single-family homes, to be clear, but what’s going on here is that it’s illegal to build anything more dense than that. If the law was changed to allow townhouses and apartment buildings to be built on that land, the area could accommodate a huge influx of new people who would live within a 10-to-30 minute walk from the new Crystal City office park as well as the job centers to the north around Pentagon City.

Thinking more regionally, the even-pricier close-in parts of the metro area — specifically the northern part of Arlington County, the portions of DC west of Rock Creek Park, and much of the Bethesda and Chevy Chase areas in Montgomery County — could easily accommodate huge amounts of transit-accessible development of the zoning code allowed it.

New York City is, overall, much denser than DC and thankfully does not ban apartment buildings across most of its terrain. Still, relative to prices, New York actually does very little building of new units these days. And the New York suburbs on Long Island have some of the most viciously exclusionary practices anywhere in America. And of course in Seattle itself where the problem of tight housing markets first started to bite Amazon, apartments are only legal in about 17 percent of the buildable land.

Ending apartment bans (and related practices like regulatory parking minimums that do apply in most of New York even where apartments are legal) would not solve every housing policy problem in the United States. But it would greatly alleviate the middle-class housing crunch while generating new property tax revenue (rather than requiring subsidies) that could be used for housing vouchers or new public housing developments.

Of course, local policymakers are deeply reluctant to change their existing zoning practices because incumbent homeowners normally like neighborhoods to stay the way they are. But if they refuse to do so, the best cure for excessive government regulation of housing markets might be for the federal government to take a less laissez-faire attitude toward these major corporate relocation questions.

America could direct corporate investment to slack markets

The economic impact of locating a new corporate campus with 20,000 highly paid jobs would be radically different in a city like Detroit, Cleveland, or Indianapolis for the simple reason that these cities have a lot of slack in their housing markets.

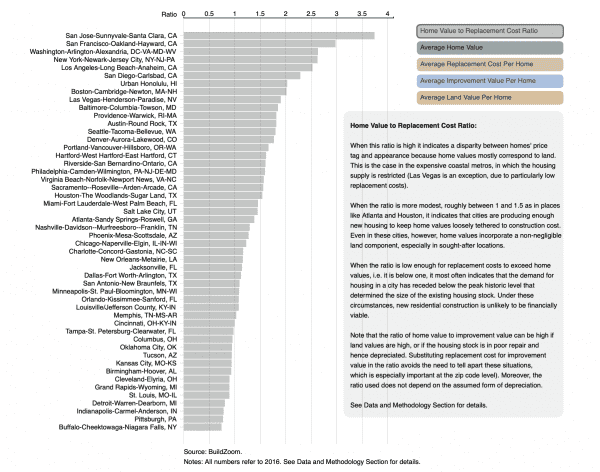

One easy way to see that is with an index that Issi Romem, an economist at Berkeley University, and BuildZoom created, which compares the average price of buying a house in a given metro area to the average “replacement cost” of a house in that area. The replacement cost is basically what you would need to spend to replace the house if it were destroyed in a tornado tomorrow.

In a healthy housing market, the ratio should be a little bit higher than 1 because the cost of buying a house includes the price of land. But in a market suffering from a regulation-induced housing scarcity problem, the ratio will soar while in a depressed market suffering from very low demand the ratio ends up being below one.

As you can see from this chart, New York and Washington already have some of the highest ratios in the country. Adding new high-end jobs to these very tight markets is only going to further squeeze the poor.

By contrast, adding a bunch of new jobs to one of the cities where the ratio is below 1 would be an incredibly useful local economic stimulus. Housing affordability is good, but when homes get more expensive to replace than to buy the market turns dysfunctional. It’s no longer economically rational for landlords to invest in maintaining the properties they own. Middle-class homeowners tend to try to keep things in good order whether or not it’s economically rational, but that simply means people are pouring time and money into a money-losing investment.

Some of these cities are clearly too small to support an office complex on the scale Amazon is talking about. But downtown Cleveland already has about 100,000 jobs in it, which is (obviously) less than central Manhattan but about double Long Island City. And the Detroit metropolitan area has a slightly higher population than Greater Seattle, though the latter will quickly overtake it. Cleveland and Detroit also feature major airports that currently operate below their historical peak passenger loads, and are blessed with first-rate cultural amenities (museums, sports teams, live performance venues, etc.) as part of the legacy of their pasts as more prosperous cities.

None of which is to say that Amazon made a mistake by opening its branch offices in two prosperous superstar cities. Tech workers, rationally, prefer to live in cities that feature multiple tech employers because that gives them exit options and flexibility. That, in turn, means that companies that want to hire tech workers like to operate in cities that other tech companies operate in. That means first and foremost the Bay Area, followed by New York and Seattle, followed by DC and perhaps Boston and Austin.

But the overall dynamic of rich cities getting richer while their low-income residents actually get poorer and the legacy infrastructure and housing stock in the midwest steadily deteriorates is profoundly dysfunctional. The wishful thinking that the HQ2 search touched off followed by its predictable endgame shows this isn’t a problem that’s going to fix itself — federal policymakers need to take a stronger hand in steering these kind of decisions if we want things to ever change.

Sourse: vox.com