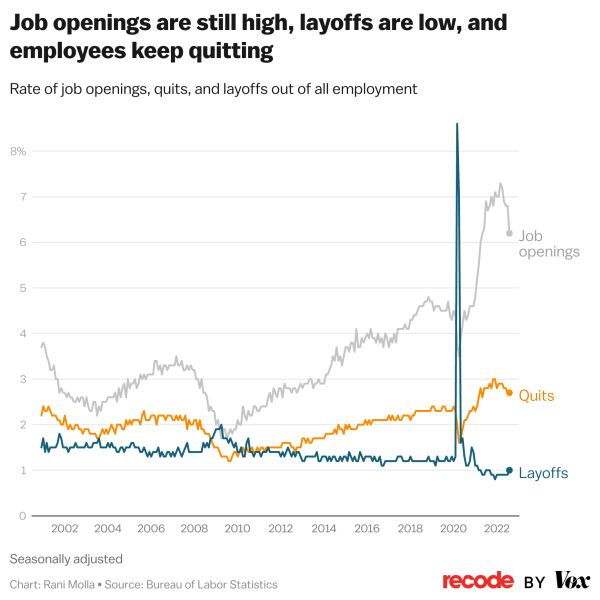

The labor market is starting to slow down. Job openings have fallen, and employers are adding fewer jobs to the economy compared to earlier in the year.

Although that may seem dim, economists say there is reason to believe that some employers could be more hesitant than in the past to lay off workers in a potential economic downturn.

In August, job openings fell to 10.1 million, down about 1.1 million openings from the month before, according to Labor Department data released on Tuesday. The same month, employers added 315,000 jobs to the economy — fewer than in July, when 526,000 were created.

The unemployment rate also rose to 3.7 percent in August — but that’s only a small increase from a 50-year low the month before.

At the same time, layoffs have remained steady. In August, layoffs ticked up slightly to 1.5 million, but that’s still modest compared to pre-pandemic levels (in February 2020, there were about 2 million layoffs).

It’s a confusing economic situation. Gross domestic product has declined, inflation is uncomfortably high, and fears of a recession have grown. But the overall job market remains strong, and many businesses can’t fill all of their openings.

A recent report from Employ Inc., which provides recruiting technology and services to companies, suggested one reason for this: While some industries were letting go of workers, others were “labor hoarding” — finding ways to hold on to workers rather than laying them off to save money in the long run. According to the report, 52 percent of recruiters surveyed said their organizations were retaining employees, even if they weren’t performing to standard or fit with the culture.

Economists say there are a number of reasons employers could be less likely to lay off workers, at least for now.

Many dealt with persistent labor shortages during the pandemic and found it difficult to hire people, so they may not want to go through the same process again. It’s also costly to onboard and train workers, so if employers think an economic downturn will be relatively short-lived, they could be more likely to retain employees.

Help inform the future of Vox

We want to get to know you better — and learn what your needs are. Take Vox’s survey here.

Aaron Sojourner, a labor economist and senior researcher at the W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, said that some employers have missed out on profit opportunities during the pandemic because they’ve struggled to find enough workers to fill open positions. That might make employers less likely to shed workers in an economic downturn since they would want to deploy workers quickly once the economy improves, he said.

“You can’t count on a long line of job applicants to just show up whenever you post an opening,” Sojourner said. “I think employers hadn’t felt that so acutely in a long time.”

And some companies are still struggling to fill open positions, meaning that, if they needed to cut back on spending, they could slow down hiring without laying people off.

Diane Swonk, the chief economist at KPMG, said industries that are still understaffed, such as manufacturing and health care, could be more likely to hold onto workers, even if economic conditions worsen.

“Even as you scale back, you’re still understaffed, so you’re not going to be firing as many as you would have,” Swonk said. “There’s also a sense that, if you work so hard to get workers, you want to retain the workers you have.”

Other evidence also suggests companies are slow to let workers go. A recent report from the Institute for Supply Management found that new orders have dropped and hiring in the manufacturing industry has slowed, but companies largely haven’t mentioned layoffs, indicating that they still feel confident about demand in the near term.

John G. Fernald, a senior research adviser at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, said that employers would be especially hesitant to lay off workers who would be difficult to rehire once the economy recovers from a downturn, such as those with specialized skills or higher levels of education.

“If you lay off people with valuable skills, well, you’re not going to be able to recover production when demand picks up again,” Fernald said.

That could be an important consideration for industries like construction, which has been affected by the drop in demand for homes as mortgage rates have skyrocketed. Ed Brady, the president and chief executive officer of the Home Builders Institute, said the organization was urging companies to retain and invest in skilled workers, even though the housing market has seen a downturn. If businesses resort to layoffs, those workers could leave for competitors in other industries, Brady said.

“We have to be thoughtful about how we keep skilled labor in this industry,” Brady said. “When you lay off people, they’re going to look for different ways to make a living and support their families.”

Employers will likely base much of their hiring decisions on what they think will happen with consumer demand, said Sojourner, the W.E. Upjohn Institute economist. If employers believe a drop in demand will be temporary, they could decide to retain workers during that period, rather than spend more money to ramp up hiring later or risk not having enough workers later. But if consumer demand plummets and keeping employees on the payroll significantly cuts into profits, businesses would be more likely to let workers go, he said.

Labor hoarding would be good for workers who can retain their jobs, but it wouldn’t stave off layoffs entirely, Sojourner said, especially if the Federal Reserve’s interest rate hikes significantly slow down the economy.

The Fed has been aggressively raising interest rates for months in an attempt to bring the fastest inflation in 40 years under control. Last month, the Fed raised rates by three-quarters of a percentage point, another unusually large increase. By doing so, the central bank is trying to get consumers to spend less on goods and services.

That should help prices come down, but it could also slow down hiring. As demand falls, businesses could decrease production and cut down on costs, leading to a pause in hiring or eventually layoffs. Jerome Powell, the Fed chair, has said the labor market is unsustainably strong and that unemployment will likely rise as the Fed tries to bring down inflation.

Many high-profile tech companies, such as Netflix, Microsoft, and Snap, have already laid off hundreds of employees this year as executives have grown warier about the Fed’s policy moves and the trajectory of the economy. The tech sector also ramped up hiring earlier in the pandemic, so the wave of layoffs may be, in part, a return to more normal staffing levels.

Allie Kelly, the chief marketing officer of Employ, said that industries beyond the tech sector have started to pull back on hiring in recent weeks, according to the company’s data. Within days of the Fed’s latest interest rate hike, there has been a “clear, growing trend” of more companies implementing hiring freezes, she said, although they still largely aren’t laying off workers yet.

“There will likely be layoffs if there is a recession, even if labor hoarding mitigates how severe those layoffs may be,” said Daniel Zhao, a lead economist at Glassdoor.

Our goal this month

Now is not the time for paywalls. Now is the time to point out what’s hidden in plain sight (for instance, the hundreds of election deniers on ballots across the country), clearly explain the answers to voters’ questions, and give people the tools they need to be active participants in America’s democracy. Reader gifts help keep our well-sourced, research-driven explanatory journalism free for everyone. By the end of September, we’re aiming to add 5,000 new financial contributors to our community of Vox supporters. Will you help us reach our goal by making a gift today?

Sourse: vox.com