How McCarthy got into this mess, who’ll be speaker next, and more.

Then-House Speaker Kevin McCarthy walks through the Capitol on the eve of his ouster. Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

Former President Donald Trump has endorsed Rep. Jim Jordan (R-OH), a conservative firebrand and the powerful chair of the House Judiciary Committee, to be the next House speaker.

In a Friday post on his social media platform Truth Social, Trump said Jordan “is STRONG on Crime, Borders, our Military/Vets, & 2nd Amendment … He will be a GREAT Speaker of the House.”

Trump’s endorsement will likely help Jordan, but may not be enough to ensure he defeats his chief rival for the speaker position, Louisiana’s Rep. Steve Scalise, the Republican majority leader. At the moment, both appear to be struggling to capture the 218 votes needed to become the next speaker.

As each lawmaker works to solidify support, legislative business in the House has ground to a halt at a moment when lawmakers are staring down a fast-approaching November deadline to fund the government for the next year.

All this comes after House Republicans ousted Rep. Kevin McCarthy (R-CA) as speaker in an unprecedented vote, leaving them scrambling to pick a replacement who can unify a caucus that has recently struggled to agree on key legislative priorities.

The party’s more conservative and far-right members had long been a thorn in McCarthy’s side and finally brought about his downfall less than 10 months after he won a hard-fought contest for the speakership. Democrats refused to save McCarthy after he ruled out making concessions in exchange for their support.

The speakership drama has been yet another display of congressional dysfunction wrought by the GOP, just days after Republican hardliners prepared to shut down the government over a laundry list of unattainable demands. And it raises doubts about whether anyone can keep the Republican caucus in line enough to carry out the basic functions of the House — or if chaos will continue regardless of who’s in the speaker’s chair.

Here are your biggest questions about the fallout from McCarthy’s ousting and what could happen next, answered.

1) How did McCarthy lose the speaker job?

Rep. Matt Gaetz (R-FL) led the charge to strip McCarthy of the speakership after he cut a deal with Democrats to fund the government for another 45 days — just before it would have otherwise shut down at the hands of right-wing rebels in the caucus. Gaetz brought a motion to vacate on the House floor, a procedural move that had never before been successfully used to oust a speaker.

This time, however, was different.

Although McCarthy had most of his caucus behind him, he needed a majority of the House to vote against his removal to stay in power. At the moment, the GOP has a four-vote majority, and on October 3, a total of eight Republicans joined all present Democrats in voting to depose McCarthy. Five of them — Reps. Andy Biggs (R-AZ), Ken Buck (R-CO), Eli Crane (R-AZ), Bob Good (R-VA), and Matt Rosendale (R-MT) — are members of the ultra-conservative House Freedom Caucus.

That was it for McCarthy.

2) How did we get to the point where a motion to vacate was filed?

The key thing to know here is that McCarthy came in as a weak speaker who got the top job by making promises that would ultimately be difficult to keep — and concessions that would lead to his undoing.

His elevation to speaker took place after an excruciating four days and 15 ballots of voting this January — the messiest speaker election since 1860. During that process, he had the loyalty of most House Republicans but struggled to lock down support from about 20 right-wing holdouts. Eventually he got enough of them, in part by making various promises about how spending bills would be handled. He also agreed to a rule that lets any House member force a vote on his ouster at any time — handing his critics a powerful weapon, the “motion to vacate the chair.”

Then McCarthy had to actually govern the House in a time of divided party control of government. With Republicans unable to pass any laws on their own, the issues that inevitably rose to the top of the agenda were the “must-pass” measures Congress perpetually grapples with: the debt ceiling, and funding of the federal government. Many conservatives hate voting for both of these, and they especially hate any deal with Democrats struck over them. But actually breaching the debt ceiling or keeping the government shut down forever would be a disaster for the country and likely a political disaster for the GOP.

So McCarthy tried to convince the far right that he was driving as hard a bargain as he could with President Joe Biden and Senate Democrats on those matters. He kept his GOP conference united through the debt ceiling talks, eventually arriving at a pretty reasonable compromise in late May that lifted the debt ceiling.

But the government still had to be funded by September 30 or a shutdown would ensue. And that’s where things went off the rails. McCarthy could not fulfill the various promises he’d made about how spending bills would be handled, and couldn’t get many of the same GOP holdouts who wouldn’t support his speakership bid to back anything halfway realistic.

As the deadline approached, McCarthy made various attempts to unite Republicans around a negotiating strategy, all of which failed. He also threw some red meat to the base — for instance, by announcing last month that he was opening an impeachment inquiry into President Biden — which many viewed as an attempt to pacify the hard right before the inevitable ugly spending deal.

Gaetz sharply critiqued McCarthy’s efforts throughout the entire process, eventually saying he and his allies wouldn’t back any short-term deal that would keep the government open as full-year spending negotiations continued. With hours to go before a shutdown, McCarthy finally put up exactly the sort of stopgap bill Gaetz was against for a vote. It passed due to Democratic backing, averting a shutdown for 45 days.

After that, Gaetz struck, saying McCarthy had been a failed leader, and used the motion to vacate to force a vote on McCarthy’s ouster.

Rep. Matt Gaetz exits the Capitol following Rep. Kevin McCarthy’s ouster as speaker. Drew Angerer/Getty Images

3) Why did some Republicans want McCarthy gone?

Most of the eight Republicans who voted to oust McCarthy cited the 45-day government funding bill, saying it was a symptom of his broader failure to secure big enough conservative wins and change the way things are done in Washington.

Many of McCarthy’s opponents want to see spending cuts that seem clearly unrealistic, and wanted to have extended debates on full-year spending bills there was simply no time for (unless these discussions were held while the government was shut down).

But some had other motivations. Gaetz, who led the charge, has reportedly blamed McCarthy for letting a congressional ethics investigation into him proceed. The Justice Department had investigated Gaetz over a purported sexual relationship with a 17-year-old, but the probe ended in no charges for him. But the House Ethics Committee’s probe of Gaetz continued this year, focusing on “allegations that he may have engaged in sexual misconduct, illicit drug use, or other misconduct,” per CNN. McCarthy has repeatedly said Gaetz wanted him out as revenge for the ethics investigation, something Gaetz has often denied.

Meanwhile, Rep. Matt Rosendale (R-MT) is expected to run for the Senate, and this could conceivably help him appeal to the GOP base in a primary. Rep. Nancy Mace (R-SC) was a surprising defector with a complaint from the left; she claimed McCarthy didn’t do enough for women in the post-Roe era. But the others — Reps. Andy Biggs (R-AZ), Tim Burchett (R-TN), Eli Crane (R-AZ), Bob Good (R-VA), and Ken Buck (R-CO) — have been pretty consistent anti-spending hardliners.

4) Why didn’t Democrats save McCarthy — and should they have?

As Gaetz’s motion to vacate loomed, Washington was full of speculation over whether Democrats would save McCarthy, who after all had just helped keep the government open.

It is unclear whether McCarthy engaged in any serious effort to make a deal with Democrats to keep his job. Jake Sherman of Punchbowl News reported that McCarthy called House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries (D-NY) the night before the vote, and that he told his Democratic counterpart he wasn’t open to making any concessions to save himself. After his ouster, though, McCarthy told the GOP conference (per Sherman) that the Democrats came to him trying to make a deal, but that he didn’t want to.

Democrats had a lot of say over what happened to McCarthy — his narrow majority meant he’d be able to keep his job if even just a handful of Democrats decided to back him. In the end, though, none did. The party voted instead to kick him out, providing 208 of the 216 votes for his ouster.

Bad blood is one reason. Many Democrats simply dislike McCarthy and think he’s been a terrible speaker. Grievances include his kicking some Democrats off committees, opening the impeachment inquiry into Biden, and generally minimizing both Trump’s attempt to steal the election and the January 6, 2021, attack on the Capitol.

Far from thanking McCarthy for keeping the government open, many Democrats were furious about how he handled things — they complained about him jamming a bill they hadn’t read on them at the last minute and about a TV interview in which he preposterously tried to claim that it was Democrats who really wanted a shutdown.

Democrats also likely believe that headlines about messy GOP House chaos are good for Democrats politically. The party’s goal is to beat the GOP and win back their own majority, not to help them be more reasonable.

Yet the risk is that they’ve traded the devil they know for one they don’t. Say what you will about McCarthy, he did avoid a debt ceiling breach and a government shutdown. The next speaker, seeing what happened to McCarthy, may well feel compelled to cater even more to the hard right’s demands.

5) It seems like speaker drama happens to House Republicans a lot. Why are they so dysfunctional?

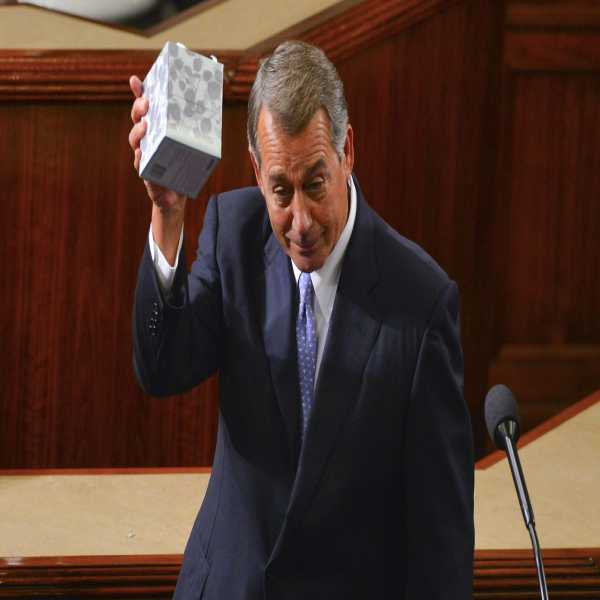

McCarthy is the first speaker to be deposed in this way, but Speaker John Boehner was also headed for that fate in 2015 — he just resigned before the motion to oust him was voted on.

Giving his resignation speech, then-Speaker John Boehner jokingly offers any colleagues a box of tissues to wipe away their (nonexistent) tears. Jahi Chikwendiu/The Washington Post/Getty Images

Internecine warfare and revolts against the speaker have been a common feature of House GOP politics in recent years, in a way that precedes Donald Trump’s rise to power and that we simply don’t see replicated among Senate Republicans or Democrats in either chamber. We can think of the problem in three parts.

First, there has long been a rump faction of the House GOP that is uninterested in governance or compromise — because they hold extreme policy views, because they want to pander to the conservative base for political reasons, or both. (The leftmost members of the Democratic Party, by contrast, have generally been willing to cut deals and to back party leadership when asked.)

Second, some quirks of House rules give that rump outsize power. The speaker is elected by the whole 435-member House of Representatives, not just its GOP members. So if McCarthy couldn’t win over any votes from Democrats, that means, if all members are present and voting, he would need 218 Republicans to back him to be speaker. That’s why he struggled so much back in January to win the speakership in the first place.

There is no similar mechanism in the Senate, where party leaders are elected privately by senators of their own party. Additionally, the motion to vacate the chair rule allows any troublemaking member to essentially force a vote of no confidence in the speaker before the full House — McCarthy had hoped to raise the threshold, but gave in to holdout Republicans who have now used this tool to force him out.

Third, because Democrats did better than expected in last year’s midterm elections, the Republican House majority was historically small — just 222 Republicans were elected. That means that, again, unless McCarthy won over Democrats, he needed to hold onto almost all of the hardest of the GOP’s hardliners to be elected speaker or to survive the motion to vacate. He actually did a decent job of pacifying most of them, but in the end, eight were enough to fire him.

6) Can Congress function without a House speaker?

The House cannot function as normal without a speaker. Rep. Patrick McHenry (R-NC) was appointed interim speaker as Republicans work to figure out who will lead their caucus, and the House, from here. But he can’t bring legislation to the House floor as speaker pro tempore.

That means that regular business in the House will be interrupted until a new speaker is selected. And that, if the past is predictive, could take days.

Again, it took four days, lots of concessions, and 15 rounds of voting before McCarthy finally won the speakership. Given that divisions between those conservatives and moderates in the GOP conference are deeper than ever — with some McCarthy allies even crying on the House floor and suggesting that there may have been physical altercations had the chamber not adjourned immediately after McCarthy’s ouster — this vote could play out similarly. Democrats, for their part, plan to vote for Minority Leader Jeffries, meaning that Republicans will have to reach near-consensus on a new speaker.

House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries, right, confers with Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer ahead of a July 2023 voting rights event at the Capitol. Jabin Botsford/Washington Post/Getty Images

The search for a new speaker threatens to delay several key legislative priorities, including a deal to prevent the government from shutting down in November and funding for the war in Ukraine.

Financial analysts have projected that the likelihood of a government shutdown when the temporary stopgap funding expires on November 17 has increased now that there is a leadership vacuum in the House. The next speaker faces the difficult task of balancing the demands of conservative hardliners with the reality of having to pass a spending bill that Democrats in the White House and Senate would support.

Funding for the war in Ukraine has also proved a sticking point in the spending fight amid waning public support for continuing to aid the country’s war efforts against Russia. Conservative hardliners — including possible replacement Rep. Jim Jordan (R-OH) — have opposed sending further funds, and the stopgap funding deal that McCarthy negotiated did not include funding for Ukraine, which is running low on money and munitions.

Though the House can’t bring legislation to the floor, other business in the chamber can proceed — albeit potentially on a delayed basis. That includes House Republicans’ impeachment inquiry of Biden, which had a bumpy start during a hearing in which Republicans struggled to tie the president to the alleged misdeeds of his son, Hunter Biden.

The House Oversight Committee is continuing to review documents, records, and communications relating to the impeachment inquiry and will take further action in the coming days, according to an aide for the committee. Committee chair James Comer (R-KY) himself insisted after McCarthy was deposed that the speaker fight “doesn’t change anything.” However, Rep. Jason Smith (R-MO) said it would actually “stall and set back efforts to hold President Biden accountable.”

7) Who could replace McCarthy?

Scalise was the heir apparent to the speakership, but some in the House worried a cancer diagnosis could derail those plans. He did announce in September that he has pursued aggressive treatment for his multiple myeloma, which has significantly improved his long-term prognosis, and has emerged as one of the leading candidates in the speakership race.

Scalise was among multiple people who were injured when a gunman fired at lawmakers on a baseball field in 2017, and he has been touting himself as a strong fundraiser: In 2022, his reelection campaign raised nearly $19 million, second among House Republicans only to McCarthy’s reelection campaign, which raised over $28 million.

However, McCarthy allies are reportedly trying to torpedo Scalise’s candidacy. That would advantage Jordan, who previously challenged McCarthy for the speakership but had since become one of his biggest supporters on the party’s right flank. He raised more than $14 million in 2022, making him the fourth-most prolific fundraiser among House Republicans. His endorsement from Trump could be a boon, especially among the caucus’s further right members.

Both Scalise and Jordan may still struggle to capture moderate support, potentially leaving an opening for other candidates. McHenry has apparently ruled out running for the speakership, despite occupying the position temporarily.

House Majority Leader Steve Scalise speaks with House Judiciary Committee chair Jim Jordan, left, in front of the Capitol in 2019. Tom Williams/CQ-Roll Call/Getty Images

Other potential contenders include Republican Study Committee head Rep. Kevin Hern (R-OK) and Rep. Tom Cole (R-OK), the Rules Committee chair. Hern was previously nominated during the January speaker fight, but received only a few votes and voted himself for McCarthy.

Cole, a bipartisan operator who has been an ally of the past three Republican speakers, warned that removing McCarthy would result in chaos and criticized his party’s right wing for seeking his demise.

Some Republicans have even floated former President Donald Trump for the speakership. There has never been a House speaker who wasn’t already a sitting member, but outsiders are technically allowed to run. Trump has declined to run in the past, and but told Fox News he’d consider stepping in as an interim speaker should it become clear that no one else could get 218 votes. At the moment, he would be barred from becoming speaker by House Republicans’ own rules, given that he’s been charged with felonies that carry potential prison sentences of two or more years; those rules, however, could be changed.

After saying he wouldn’t seek the speakership again in the days after his deposal, McCarthy suggested recently that he would be open to taking his old job again, saying, “whatever the conference wants, I will do.” Some of his allies argue he’s the only member of the GOP caucus with a real shot at getting the votes needed to take the gavel, though he’d face massive opposition from those who worked to remove him.

It’s hard to see right now how any of these candidates have a clear path to the speakership, and how whoever becomes speaker will be able to wrangle a divided caucus. Republicans are scheduled to begin the selection process on Tuesday in a private candidate forum, where a majority of Republicans would have to vote to endorse a candidate before voting on the House floor.

8) Could a bipartisan power-sharing deal be possible?

The West Wing fantasy for the way this all ends: Enough reasonable Republicans are so disgusted at their colleagues’ extremism that they cut a deal with Democrats to provide votes for a new moderate speaker, resulting in much saner governance.

In our polarized and partisan reality, it’s a different story. One of the first acts of speaker pro tempore McHenry was to order former Speaker Nancy Pelosi to clear out of her office space in the Capitol, in an obvious act of resentful retribution aimed at Democrats for supporting McCarthy’s ouster. And so far, Republicans have uniformly said that the choice of the next speaker will be made by the GOP conference, not by Democrats. Most in the GOP may be furious at Gaetz and his compatriots, but the only thing worse than winning them over is dealing with Democrats.

The vast majority of Republican members of Congress are Republican partisans who rely on campaign money from Republican donors and party leaders, represent Republican districts, cater to Republican-aligned activists, socialize with other Republicans, and need to win Republican primaries. Breaking out of that ecosystem is difficult and risky, and usually means the end of one’s political career, as former Rep. Liz Cheney found out. The incentives to keep politicians on the team are likely too powerful to overcome.

9) What are the bigger-picture consequences of all this?

In the short term, the House looks more dysfunctional than ever. McCarthy being deposed due to failure to appease the far right pretty obviously sets the stage for further dysfunction and crisis as far-right members try to flex their muscles even more.

But much remains uncertain about the longer-term consequences. Things could play out in a few ways.

One big question for the rest of this year and 2024 is whether McCarthy’s successor will manage to somewhat stabilize things in the GOP. That may seem unlikely, but it’s not impossible. After Boehner was effectively pushed out in 2015, his successor Paul Ryan never faced a comparable revolt from the right. Hardliners appeared to feel that they’d made their point, and they chilled out a bit. Of course, things could always get worse, too.

Another question is what this means for the 2024 elections. Democrats shouldn’t count on internal GOP drama leading them to victory. In recent presidential cycles, congressional election results have pretty closely followed what happens at the top of the ticket. The presidential matchup will likely be far more important in determining the House majority than the House’s own internal machinations will. And the size of that next majority will help determine whether tactics like Gaetz’s will be likely to succeed again.

Still, it’s clear that none of this is particularly good for the stability of American governance. The incompetence and extremism on display throw the basic functioning of the federal government into question. It’s not a good place for American democracy to be.

Update, October 10, 9:25 am: This story, originally published October 4, has been updated several times, including with news that Trump endorsed Jordan for the speakership and that McCarthy is willing to be considered for the speakership again.

Sourse: vox.com